General George Washington at Valley Forge: Keep a “strict watch” Out For the Enemy, “and you may perhaps repay them”

He illustrates his leadership qualities, insisting on remaining alert and observant, with an emphasis on action

“You may depend that this will ever be the consequence of permitting yourself to be surprised…It is not improbable that the Enemy, flushed with their success, will soon be out again…”

This is just the fourth letter of Washington at Valley Forge that we have carried in all our 30 years

...“You may depend that this will ever be the consequence of permitting yourself to be surprised…It is not improbable that the Enemy, flushed with their success, will soon be out again…”

This is just the fourth letter of Washington at Valley Forge that we have carried in all our 30 years

General George Washington did not have a passive strategy for winning the American Revolution, nor was he simply biding his time hoping to wear out the British. The truth is that he believed in, and was most comfortable with, pursuing an aggressive strategy against the British whenever he could. In 1775, he supported the invasion of Canada, attempting to find in the French Canadians allies in the struggle who might open up a second front. This was not successful, but it did not deter Washington’s taste for taking the initiative. After the loss of New York in 1776, he planned and executed the high-risk – and successful – maneuver of crossing the Delaware River on Christmas Eve to attack the Hession garrison at Trenton. When the British came down from New York to contest his position near Princeton in January 1777, Washington engaged them, then pretended to withdraw, and instead circled around to attack them. The American cause tasted victory.

But in September and October of 1777, Washington suffered serious reverses in Pennsylvania at the battles of Brandywine and Germantown; the British then occupied Philadelphia, driving away the Congress. By November, the Americans were encamped around Whitemarsh, 12 miles from Philadelphia. Washington’s inclination was still to attack and retake the city, but he dared not because his forces were in poor condition and a failure might well mean the end of the Continental Army. He said, “Our situation…is distressing from a variety of irremediable causes.” He also considered changing his encampment if he could get away. A move to Valley Forge, 20 miles from Philadelphia, would be advantageous because he could keep an eye on the enemy in Philadelphia in a location that was easily defended, had abundant water, and plenty of wood for fuel and making huts for the winter.

After an exhausting march from Whitemarsh, the American force of 8,000 Continentals and 3,000 militia arrived at Valley Forge on December 19, and they were in a miserable state (just four days later nearly 3,000 men were reported sick or incapable of duty). The winter came on and the men suffered badly from the cold. Except for officers, they slept in six-foot square tents made of canvas, which were weak and cracked and didn’t provide sufficient protection from the snowy weather. Clothing was in very short supply, and many soldiers had to go barefoot or wear only one layer of clothes (at one time 4,000 men were so destitute of clothing that they could not leave their tents). The food, when available, was inadequate. Smallpox and other diseases also ravaged the army at Valley Forge. By mid-winter, 5,000 men had died or left because of illness or the awful conditions. The entire American Army thereafter consisted of some 6,000 men huddled on frozen ground around campfires. British general Howe, by way of contrast, had some 15,000 well-supplied men in and around Philadelphia, and many more available in nearby New York.

On March 28 and 29, word of two important events reached Valley Forge. The first was the news that on February 6, France and the United States had signed a Treaty of Alliance in Paris. This meant recognition of American independence, as well as the eventual arrival of supplies, munitions and French troops to participate in the war. The second was information that four British regiments were believed to have left New York by ship, possibly bound for Philadelphia to aid in an attack on the American encampment. Washington considered acting first and proposing an offensive. According to “Ordeal at Valley Forge” by John Stoudt, knowing that he must act on both the offensive and defensive, and soon, Washington “busies himself late into the night with plans for the next campaign.” So we can see that Washington was already shifting from thinking about defense and turning his attention to the offensive.

John Lacey served as an officer in a Pennsylvania regiment of militia, with which he fought at the Battles of Germantown and Matson’s Ford. He gained such a reputation for skill and courage that Pennsylvania Supreme Executive made him a Brigadier General of Pennsylvania Militia on January 9, 1778. At that time Lacey was named to command the Pennsylvania militia covering the northern approaches to Philadelphia between the Schuylkill and Delaware Rivers, and was responsible for intercepting parties of Tories and farmers entering the city, and for keeping an eye out for information on the British forces in and around Philadelphia. His force was small, but Lacey nevertheless hoped to cause trouble for the British, writing Washington on April 27, 1778, from Crooked Billet, where he had just stationed his troops: “I hope in a few days to be able to annoy the Enemy should they continue their late practice in coming through the Country.” But repeated small-scale raids had demonstrated to the British the weakness of Lacey’s force, and Lacey’s movement to Crooked Billet made him vulnerable to attack. Accordingly, on the night of April 30 two columns of British troops left Philadelphia and approached Crooked Billet under cover of darkness, determined to seize the opportunity to surprise the unsuspecting Americans. The British force was 800 men, among them 100 dragoons, sent in two columns.

The Americans were surprised, but Lacey’s men spotted the Queen’s Rangers and began to retreat before the British infantry was in position. A member of the British force wrote: “One of the detachments was spotted by the enemy before the second one arrived, whereupon [Lacey’s militia] made a hasty retreat…The first detachment, with the dragoons, eager for some action, attacked the enemy, who, however, fled in such haste that our infantry could not catch up with them. But the 100 dragoons assaulted so furiously that they captured 53 and left 30 killed on the field…We had only a few wounded. The encampment of huts of the enemy was set on fire and 10 wagons, which were loaded with baggage, etc., were brought in by our men.”

Lacey reported this debacle to Washington in a letter sent on May 2, saying: “My Camp was Surrounded Yester. Morning by Day Light With a body of the Enemy who appeared on all Quarters. My Scouts neglected the preceding night to patrol the Roads as they were ordered, but lay in Camp till Near day…The officer who Commanded Says he Was So Near the Enemy before he spied them, that he thought it dangerous to fire, but Sends off one of his party to alarm the Camp who did not Come. On the Disobedience & Misconduct of this officer, I have to Lay my Misfortunes. The Alarm was So Sudden I had Scarsely time to mount my Horse before the Enemy was within Musket Shot of My Quarters…My Loss is Near thirty Killed & wounded the numbers taken Prisoner cannot be assertained I think it cannot be many – Several were inhumanly Butchered after they had Surrendered…”

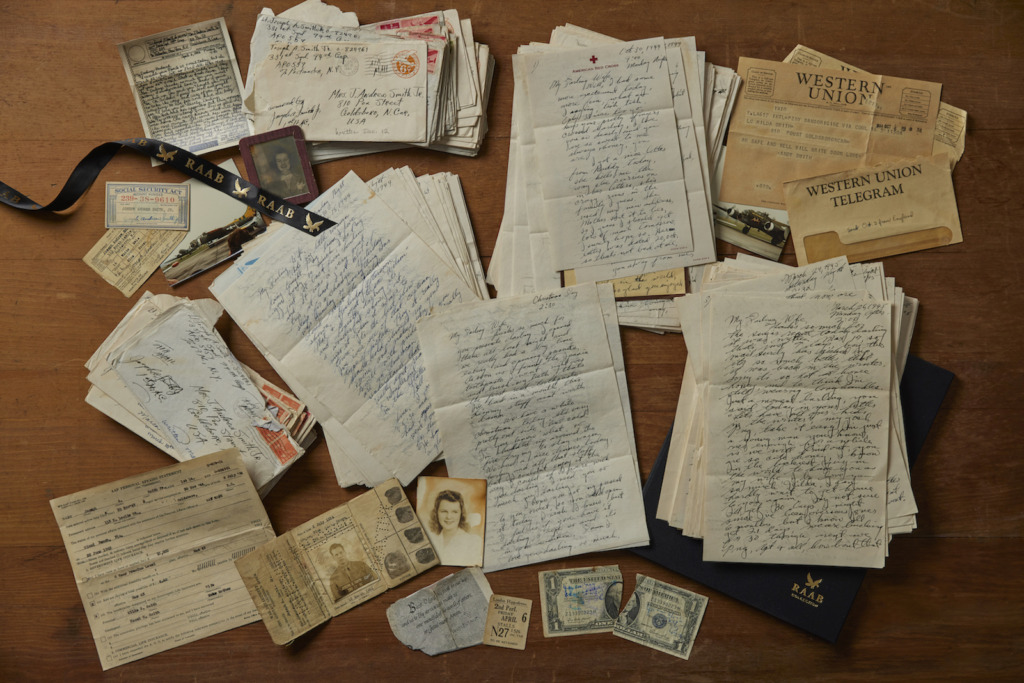

Washington responded the next day, showing impatience with the fact that the Americans were surprised, insisting that anyone responsible for that surprise be courtmartialed, and then insisting that Lacey take a more aggressive stance, as he [Washington] would have done. Letter signed, Head Quarters, Valley Forge, May 3, 1778, to Lacey. “I received yours of yesterday giving me an account of your misfortune. You may depend that this will ever be the consequence of permitting yourself to be surprised, and if that was owing to the misconduct of the Officer who was advanced, you should have him brought to trial—It is not improbable that the Enemy, flushed with their success, will soon be out again, if you keep a strict watch upon their motions you may perhaps repay them.” The text of this letter is in the hand of Tench Tilghman. The day after this letter, May 4, 1778, Congress ratified the treaty of alliance with France.

In our three decades in this field, we have only had three other letters of Washington from Valley Forge. This is a particularly fine one, showing Washington illustrating his leadership qualities, insisting on remaining alert and observant, with an emphasis on action.

Washington and the Continental Army left Valley Forge in mid-June 1778. Though no battle was ever fought there, Valley Forge was a turning point in the war. The Continental Army could well have disintegrated from discouragement and hardship, but the soldiers’ faith in Washington kept it together. The name Valley Forge thereafter provided a rallying point, showing that the troops were determined to carry on the fight no matter what. Moreover, Washington used the time there wisely, having Baron von Steuben train the troops and turn them into true fighting men whose newly acquired skills would lead them to future victories. Valley Forge is America’s greatest enduring symbol of the struggle for freedom, as is expressed by the words carved into the memorial arch at Valley Forge National Park: “And here in this place of sacrifice, in this vale of humiliation, in this valley of the shadow of that death out of which the life of America rose…Let us believe with an abiding faith…that liberty [will seem] as sweet and progress as glorious as they were to our fathers and are to you and me, and that the institutions which have made us happy…shall bless the remotest generation of the time to come.”

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services