Gen. George Washington Approves the Retirement of Gen. John Glover, Whose Men Rowed Him Across the Delaware River That Fateful Christmas Eve 1776

It was the event that turned the fortunes of war the American way.

Glover’s actual 4 page resignation letter is included, in which he discusses his service and explains that his health will not permit him to continue: “I must confess it will be with reluctance that I leave so good a cause before the work is finished, and in particular to serve your Excellency…”

...Glover’s actual 4 page resignation letter is included, in which he discusses his service and explains that his health will not permit him to continue: “I must confess it will be with reluctance that I leave so good a cause before the work is finished, and in particular to serve your Excellency…”

At the start of 1776, John Glover and his experienced Marblehead seamen became the 14th Continental Army Regiment and in July joined George Washington and the bulk of his forces on Long Island. In a series of maneuvers, British General Sir William Howe outflanked the Americans driving them back against the East River until they were nearly surrounded. Their only hope was to somehow escape across the river to Manhattan. During the night of August 29, Glover and his Marbleheaders ferried 9,000 Continental troops and all of their equipment, guns, horses, and cannon, at night and under adverse weather conditions. More defeats compelled the Americans to flee across New Jersey into Pennsylvania, with the British in pursuit. However, when Howe was unable to get across the Delaware River, he closed his campaign for the year and marched back to winter quarters in New York City. To occupy the conquered colony of New Jersey, the British general left behind a chain of individual garrisons, the principle one of which was at Trenton. Washington grasped quickly the flaw in the British strategy: by establishing separate posts along the river, the British forces were divided and lay wide open to raids. He determined upon a daring plan to cross the Delaware on Christmas night, dash down to Trenton and smash the Hessian garrison stationed there.

The attack was a desperate gamble, but Washington felt he had no alternative. The week after Christmas the enlistments of many soldiers in his army expired, and he had to get one more battle out of these men before they left the service. The winter had been cold, and on Christmas day the river was clogged with ice, so the feasibility of the Trenton operation narrowed itself down to a single question: could Washington’s army and weaponry navigate the ice-strewn river to reach the opposite bank? The answer again depended upon John Glover, a man with drive and intelligence, whose knowledge and experience of maritime matters made him a master of amphibious operations. Washington came to look upon Glover’s men as a kind of ferrying unit ever since the regiment had proven instrumental in evacuating the American army from the precarious position on Long Island. When the attack on Trenton first had been discussed, tradition avers that Washington turned to Glover to ask if his mariners could navigate the ice-choked river. Glover murmured quietly that his boys could manage the task. Only after this assurance, it is said, did Washington proceed with his plan.

As dusk fell early on that bleak December afternoon, the boats that Washington had collected and concealed from enemy view were taken down to the riverbank. Built for river commerce, they were ideally suited for military operations because of their large size and light draft. Then the 2,400 men in Washington’s force were brought to the boats. Their march to the spot was a cruel one for thinly clad troops. One major who trailed the column to deliver dispatches recalled that the route was easily traced in the snow by bloodstains “from the feet of the men who wore broken shoes.” The men bore up under these painful conditions. Christmas night brought with it a howling storm; a wind roared down, churning the river waters and making difficult the handling of the pitching craft. The river was high and the swift and surging current was littered with ice. As the night turned colder and the wind more piercing, new ice formed on the gear. The Delaware at the ferrying place was only about 1,000 feet wide, yet Glover’s soldiers were forced to call upon all of their seaman’s skill to navigate this span. Great chunks of ice came surging downstream to hit against the boats and became obstacles impeding the forward progress of the craft. Each cake of ice had to be wrestled out of the way before the boats could continue their passage. ‘The floating ice in the river,” reported one participant, “made the labor almost incredible’. As if river conditions were not bad enough, about eleven o’clock it began to snow and Glover’s men had to deal with this additional difficulty. Yet they worked away and the patriot force on the east side of the Delaware gradually swelled in size. Ferrying the heavy howitzers and guns became the most critical part of the operation. With much effort, Glover’s men succeeded, leading Henry Knox to note aptly, “…perseverance accomplished what at first seemed impossible.”

After the crossing came the surprise victory at Trenton, which reinvigorated the American cause at its lowest point and quite likely saved the Revolution. The tale of Washington crossing the Delaware passed into legend as well as history, and became the subject of probably the best known American historical painting.

Glover left the army at the end of 1776 in order to put his personal affairs back in order, but Washington wrote him a personal letter asking that he resume a command, which he did in mid-1777. He commanded a brigade in the Saratoga campaign under General Horatio Gates, and the following year went to Rhode Island to participate in a combined American-French attack on the British at Newport. He remained for a time in Providence as commander of the American forces, then was posted to the Hudson River highlands where he served with units assigned to watch the British in New York City and, if necessary, to block their movement up the river. He remained there until 1782. That year Glover’s health took a turn for the worse, and on June 18, 1782, he wrote Washington with a request to retire.

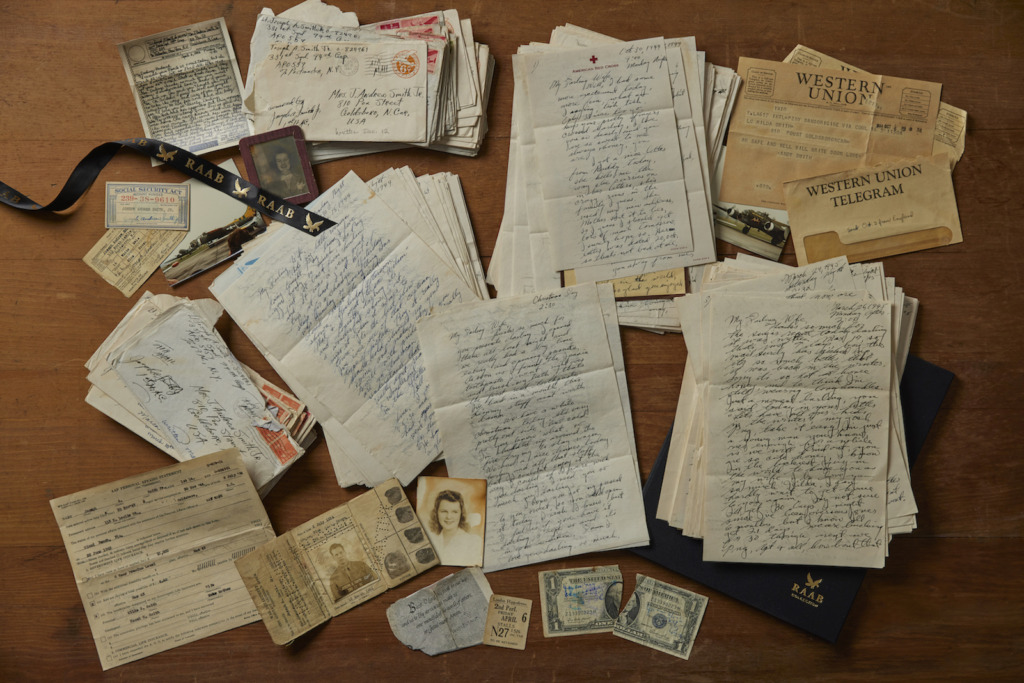

Autograph letter signed, 4 pages, Marblehead, Mass. June 18, 1782, to Washington, praising Washington and the cause for which he served, explaining the precarious situation of his health, and requesting removal from active duty. “Yesterday I was honored with your letter of the 22nd ulto. in which I am happy my conduct in appointing muster masters for districts of Springfield has met with your Excellency’s approval. Any orders in future your Excellency may please to honor me with, within this quarter, shall be particularly attended to & punctually complied with, so far as my state of health will permit; which at present is very much impaired & exceedingly precarious (God alone knows how long it may continue so) as my want of sleep, night sweats, & violent evacuations of urine, rather in excess as the warm weather comes on, than otherwise. I have for some time been under a course of ye bark & am now trying the cold bath, but as yet have not seen any benefit from either, however, am encouraged by my physicians, who are sanguine in their opinion, that a steady course strictly adhered to, & persevered in, will in time help me, taking particular care to avoid all violent heats & colds, with using very moderate exercise, such as riding five miles morning & evening in a chase [carriage] (it gives me great pain to ride on horse back) and keeping my mind entirely calm & easy – the latter I find will be very difficult to effect, as my absence from camp, at this stage of ye campaign while belonging to ye army is very disagreeable to me, and often produces many very anxious moments, least it should be [construed] into a neglect of duty, or partial indulgence; to prevent which or any other kind of censure, as well as to free the public from unnecessary expense of full pay to officers, who are not able to do duty.

“Permit me to ask the favor of your Excellency to state my case, and transmit with it, a copy of this, with the enclosed certificate, to the President of Congress, who I do most earnestly request would be pleased to lay them before that Honorable Body, and urge the necessity of my being permitted to retire upon the establishment; as from my very debilitated state of health, added to that the advance stage of Life which I am arrived to, being a few months of fifty years of age; there is not the least probability in nature of my being ever able to do the duty of a soldier again; and in the situation to be continued on the list, and to be entitled to receive full pay, while some other gentleman must do my duty is a consideration which wounds my feeling as a soldier exceedingly.

“I have endeavored from time to time to give a true and impartial account of the state of my health, which I presume will be confirmed by the enclosed certificate, from two of the ablest & approved physicians in the state, which I hope will be satisfactory to your Excellency, and have such weight in the minds of the Honorable Congress as to produce my derangement [discharge], which appears to me is but just it should take place, & that it may be done with the greatest propriety without injury to the service, or giving umbrage to any individual; especially when it’s considered how early I engaged and that I have served our country to ye best of my abilities, as long as nature could hold out, to the utter ruin of my fortune, & what is still worse, the total &irreparable loss of my constitution, as good perhaps, as any man of my age, when I entered his service.

“At the same time, I must confess it will be with reluctance that I leave so good a cause before the work is finished, and in particular to serve your Excellency, whose favor & civilities I have often experienced and for which Sir, please to accept my most cordial & sincere thanks, and believe that I am, Sir, with every sentiment of esteem & affection, your Excellency’s most obt. servt., Jno. Glover, B. General. P.S. Should the Honorable Congress not permit me to retire upon the establishment, and I be restored to a degree of health, so as to be able to prosecute the journey (which at present I am sorry to say I have not the least prospect of), I shall immediately without loss of time set off for camp.” On that page he identifies the recipient as “His Excellency General Washington”, and states that this is his retained copy.

With this letter is Washington’s original response. Letter signed, two pages, Headquarters at Newburgh, NY, July 10, 1782, to Glover. ”Sir, I have received your letter of the 18th June, with the enclosed certificate. Agreeably to your request I have forwarded a copy of your letter, with corroborating evidence of the physicians, to the Secretary of War, and recommended a compliance with your desire. That you may soon be restored to your former state of health is the sincere wish of, Sir, your very humble servant, G. Washington."

On July 30, Washington officially notified Glover that Congress had acceded to his request and allowed him to retire. His hope to retire “upon the establishment” – to get a U.S. government job – was not, however, granted. After the war Glover served in state positions – two terms in the Massachusetts State Legislature, and six terms as a Selectman for Marblehead. In 1789, President George Washington visited Marblehead and was entertained by Glover. John Glover died in 1797 at age 64.

This is unique group in our experience: the resignation letter of an important Revolutionary War general addressed to George Washington, and Washington’s return letter accepting it.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services