Admiral Horatio Nelson Writes His Heroic Flag-Lieutenant During the Battle of Copenhagen, and Conveys the Regards of Emma Hamilton

In a previously unknown and unpublished letter, he tells Captain Frederick Langford that he cannot intercede with John Hely-Hutchinson, the man who took possession of the Rosetta Stone and conveyed it to England.

At the beginning of 1801, Britain was facing Napoleon and his allies alone. Austria had been forced out of the coalition opposing France, and Russia had come to the conclusion that Britain rather than France was the greater danger. Moreover, the Baltic states (including Denmark) formed what was termed the Armed Neutrality,...

At the beginning of 1801, Britain was facing Napoleon and his allies alone. Austria had been forced out of the coalition opposing France, and Russia had come to the conclusion that Britain rather than France was the greater danger. Moreover, the Baltic states (including Denmark) formed what was termed the Armed Neutrality, asserting their rights to trade with all nations free of blockade and embargo. This concept could never be acceptable to Britain, whose chief means of imposing her will upon her adversary was controlling sea traffic by using just such means. As London saw it, the Armed Neutrality was nothing less than a direct and substantial augmentation of the French Navy. Britain impounded Danish and Swedish ships, and in March 1801 sent its Channel Fleet to the Baltic to impose its will. The fleet was under the command of Admiral Hyde Parker, and Nelson was second in command as his Vice-Admiral.

On the morning of April 2, 1801, Nelson began to advance into Copenhagen harbor. The battle began badly for the British, with three ships running aground, and the rest of the fleet encountering heavy fire from the Danish shore batteries. Parker sent the signal to withdraw, and Nelson was informed of this by his signal lieutenant, Frederick Langford, but Nelson famously responded to Langford: "I told you to look out on the Danish commodore and let me know when he surrendered. Keep your eyes fixed on him." Nelson then turned to his flag captain, Thomas Foley, and said "You know, Foley, I have only one eye. I have a right to be blind sometimes." He raised the telescope to his blind eye, and said "I really do not see the signal." The outcome of the battle was a British victory, and one of Nelson's greatest moments. As a reward for the victory, he was made commander-in-chief of the fleet and created Viscount Nelson of the Nile.

In August Nelson launched what was meant as an exploratory attack on the French flotilla in Bologne harbor. Several French ships were sunk, damaged, or driven ashore, and as a result of this success his ships’ boats mounted a full-scale assault early on morning of the 16th. Unfortunately, adverse tides meant that one whole division was prevented from taking part; and despite great bravery and determination on the part of all the officers and men involved, the attackers were forced to withdraw at daybreak having achieved only a limited success; the losses incurred were heavy. Nelson reported, "Amongst the many brave men wounded, I have, with the deepest regret, to place the name of my gallant friend and able assistant Captain Edward T. Parker; also my Flag-Lieutenant Frederick Langford, who has served with me many years; they were both wounded in attempting to board the French Commodore." Nelson wrote Emma, "Langford has his leg shot through, but will do…Parker showed the most determined courage; so did Langford." For services at Copenhagen and Bologne, Langford received a promotion to captain and is listed as commander of the 16-gun ship Fury in 1803 and of the Lark thereafter.

In October 1801 the Peace of Amiens resulted in a temporary respite from the war. Nelson returned to civilian life where he stayed with Sir William and Lady Emma Hamilton at the Hamilton's London townhouse at 23 Piccadilly. In 1802 he led a peaceful existence, in what may well have been the happiest portion of his life. However, 1803 proved to be a watershed year for Nelson, one that started with personal tragedies, and led him away from personal pursuits and back to the center of military activities. Early in the year, a second daughter was born to him and Lady Hamilton, but she died, leaving Nelson and Emma broken-hearted. Soon after, in April, Sir William Hamilton died. Diplomatic relations between Britain and France we're breaking down by then, and they had reached a crisis point when on May 15 Nelson was appointed Mediterranean fleet commander-in-chief. Britain declared war on France on May 16, and two days later Nelson became captain of the HMS Victory.

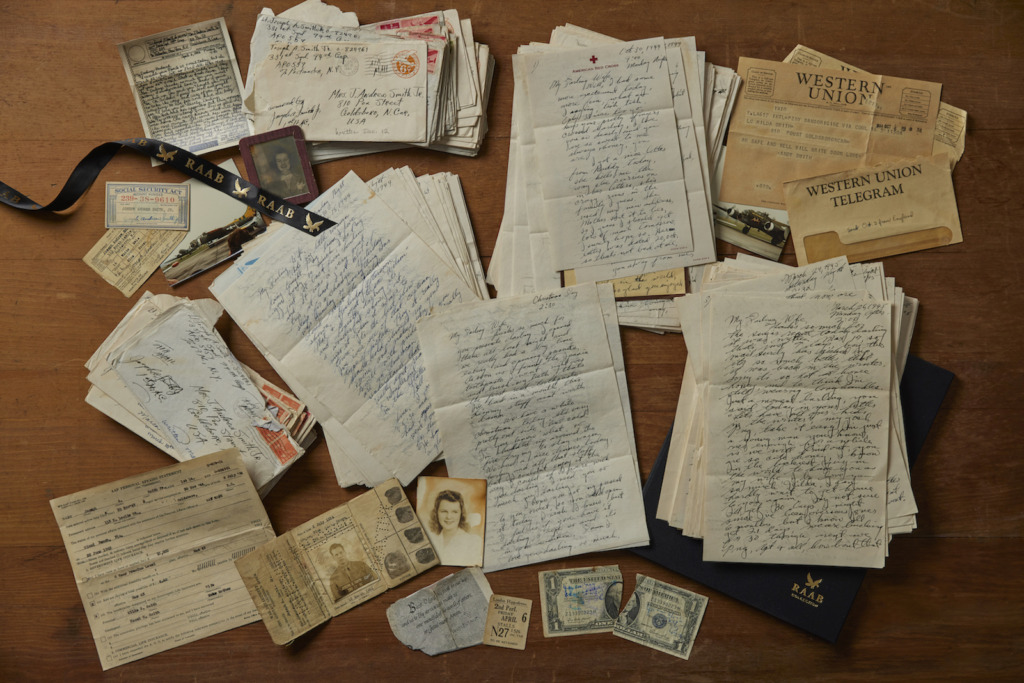

John Hely-Hutchinson was a prominent British general. In 1799, he was in the expedition to the Netherlands, and was second-in-command at the start of the 1801 expedition to Egypt. Following his superior's death in March of that year, Hely-Hutchinson took command of the force. He was the man who recognized the importance of the Rosetta Stone, insisted on taking possession of it, and saw it shipped safely to England. In late 1802 the stone was placed in the British Museum, where it remains today. It is unclear what business Captain Langford had with Hely-Hutchinson, but he sought Nelson's intervention to assist him. Autograph letter signed, 23 Piccadilly, London, February 8, 1803, to Langford. "I never saw Lord Hutchinson in my life which is a full answer to your application. I should have been happy to serve you if it had been in my power. Sir William and Lady Hamilton join in best compliments to your worthy mother and believe me ever yours most faithfully, Nelson & Bronte." Very few surviving letters of Nelson mention Emma Hamilton, this being the first we have ever had. This letter is unpublished and its existence previously unknown.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services