Victory at Yorktown: Washington Sends One of Rochambeau’s French Commanders to Join His American Counterpart in Blocking Cornwallis’s Escape

On May 4, 1778, the alliance between France and the new United States of America became effective. The Americans had high hopes for this venture, but those hopes were initially dashed. The French sent a fleet under Admiral d’Estaing in the summer of 1778; though after failing to encounter the British in...

On May 4, 1778, the alliance between France and the new United States of America became effective. The Americans had high hopes for this venture, but those hopes were initially dashed. The French sent a fleet under Admiral d’Estaing in the summer of 1778; though after failing to encounter the British in the Chesapeake Bay and making unsuccessful moves at New York and Newport, it abandoned the offensive. But Washington continued to remain hopeful, telling Lafayette in September 1779, “A corps of the gallant French would be very advantageous to the common cause." However, the French were determined to play a role, and in 1780 King Louis XVI approved a plan to send an expeditionary force sufficiently large to affect the outcome of the war. Count Rochambeau was appointed to command of the army that was destined to support the Americans, and on May 2, 1780, he sailed for the U.S. with 5,800 French troops. One of the units in this force was Lauzun’s Legion of cavalry, a unique organization within the French military made up of soldiers from throughout Europe, with an ethnic diversity ranging from France proper to the French-German border, from Russia to Italy, from Sweden and Poland to England. They were meant to be deployed overseas and are considered the predecessor of the Foreign Legion.

"He is an Officer of Rank and long Standing in the Service of his Most Christian Majesty, a Brigadier General in the Army now under Command of the Count de Rochambeau."

Meanwhile, Washington eagerly anticipated the active intervention of the French and planned a joint Franco-American campaign against British-held New York for late-summer 1780, and waited in expectation of his ally’s appearance. The French arrived in Rhode Island on July 10, 1780, and after they settled in, Washington and Rochambeau traveled to Hartford CT where they first met on September 20. They discussed coordinating a joint military operation, but since it was now clear that the remaining French troops both generals were expecting were not yet en route from France, and since no significant military operation was possible without the assistance of the French Navy, the arrival of which was not imminent, the commanders agreed that there could be no campaign in 1780.

In May 1781 some additional French troops arrived, and with them came the news that Admiral de Grasse was headed for the West Indies and had instructions to cooperate with the allied commanders in the U.S. So the allied commanders decided to march the French troops to New York to join the Americans and prepare for an attack there, supported by the French fleet under de Grasse. Rochambeau’s men arrived in July, but Washington’s expectations for an attempt on New York were soon to be disappointed. In mid-August he received a letter from Admiral de Grasse indicating that the French fleet would be available for service in Chesapeake Bay by the end of the month and would remain there until October 15. It would not challenge the Royal Navy in New York waters. Abandoning the idea of attacking New York City, Washington and Rochambeau embraced the southern campaign strategy – to rendezvous with the French fleet and attack the British under Cornwallis in Virginia. On August 18, American and French forces began moving south. The Duc de Lauzun’s Legion acted as the French advance party, remaining ten to fifteen miles south of the main army to protect the flank against any British movement.

American watercraft managed to transport some of the allied foot soldiers down the Chesapeake from Elkton, Maryland to Annapolis. The rest of the troops continued overland to Annapolis, where the infantry units halted to await boat lift further south. The allied field artillery, supply trains, and Lauzun’s French cavalry traveled southward by road to Virginia. The artillery and wagons eventually went to Williamsburg, 12 miles from Yorktown. Lauzun then received orders to reenforce the Virginia militia under General George Weedon encamped near Gloucester Courthouse on the north side of the York, and he headed there. Weedon was a friend of Washington who served as one of his Continental Army generals all the way from 1776 to the late winter at Valley Forge. Now he led the Virginia militia at this key juncture at Yorktown.

Washington and Rochambeau, accompanied by a few of their staff officers, took a different route from the main army. From Baltimore, they crossed the Potomac River at Georgetown, passed through Alexandria, Virginia, and then stopped briefly at Mount Vernon, Washington’s plantation home, which he had not visited for more than six years. The allied commanders rested at Mount Vernon on September 10 and 11. They arrived at Williamsburg on September 14, and on the 28th moved forward to start the siege of Cornwallis’s army at Yorktown.

Both Weedon’s militia and Lauzun’s Legion were assigned to Gloucester during the entire siege, and the reason was simple: Gloucester Point was just a mile across the narrows from Yorktown and was Lord Cornwallis’s best potential escape route, so sealing off that route was a top priority. Lauzun wrote in his memoirs that Gloucester was being "watched by a corps of three thousand militiamen under the continental Brigadier-General Weedon." Washington suggested, Lauzun said, that he would tell Weedon that Weedon could have "all the honours" of war but forbid him "to interfere in any way" with Lauzun’s contingent.

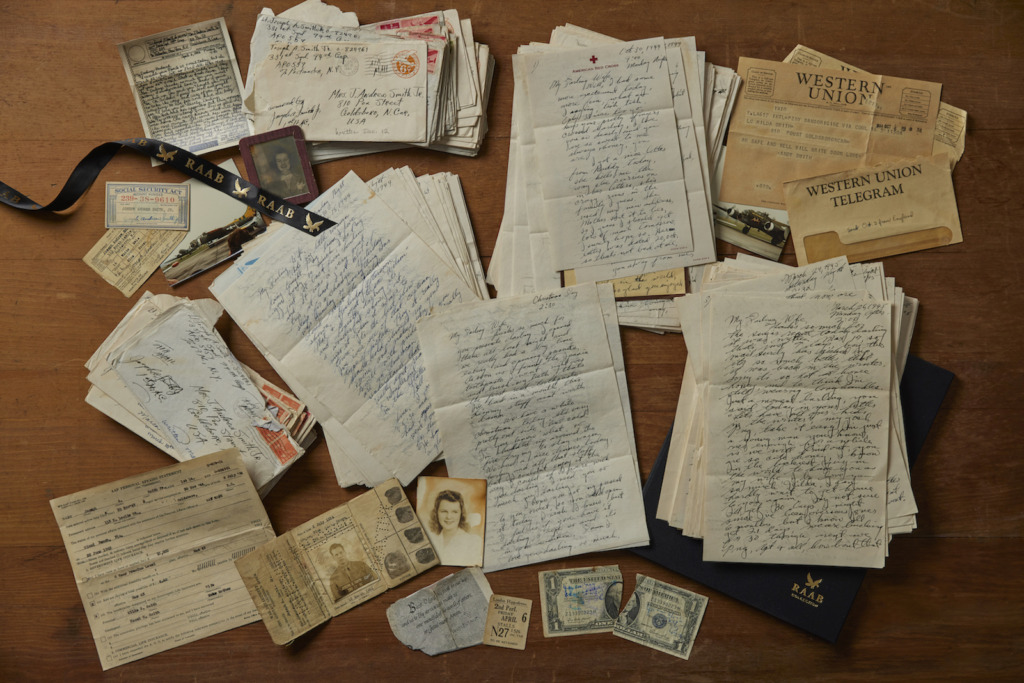

This is the letter Washington wrote to Weedon to introduce him to Lauzun, written as he was returning from a shipboard conference with de Grasse, where they coordinated the final siege of Yorktown. Letter Signed, “In James River [aboard the ship Queen Charlotte en route to Williamsburg, VA],” September 20, 1781. “The Duke de Lauzun Comandr. of the Legion of his own Name, will have the Honor to deliver you this. He is an Officer of Rank and long Standing in the Service of his Most Christian Majesty, a Brigadier General in the Army now under Command of the Count de Rochambeau. You will be pleased to shew him all that Respect and Attention, that his Rank and Services justly demand.” The text is in the handwriting of Jonathan Trumbull, jr. The letter was de-accessioned by a state historical society. Letters of Washington from the Yorktown Campaign are great rarities. This is among a very few publicly offered for sale in at least the last half century.

Once his infantry had disembarked ahead of Rochambeau's main army near Jamestown on September 23, Lauzun set out for Gloucester, where he joined his cavalry on the 28th. Cornwallis had fortified the town of Gloucester, a hamlet of four houses, with entrenchments, four strong redoubts and three batteries with 19 pieces altogether, mostly 18-pounders. Some 1100 British infantry and cavalry were also there. On October 3, 1781, at the Battle of the Hook, French and British cavalry skirmished at Gloucester, with the French being aided by the American militia. The British cavalry commander, Banastre Tarleton, was unhorsed, and Lauzun's Legion drove the British back within their lines in the town; the allies now controlled the area and Tarleton’s cavalry was blocked, and unable to reach the point, rendered useless to Cornwallis. Fifty British were killed or wounded, including Tarleton, who was much hated by the Americans for his notorious cruelty. Washington was elated by this victory; his decision to send units to Gloucester had payed big dividends.

Cornwallis was now cut off from escape or reinforcement, either by land or sea, at Yorktown. Together, the American and French land forces laid siege to the town. The French fleet under the command of de Grasse blocked the Chesapeake Bay from British reinforcement, as well as from possible escape that way. On October 19, 1781, three week after the siege began, General Cornwallis surrendered to the allies. Weedon was given the honor of securing the surrendered British arms. As a result of this catastrophe to their arms, the British lost heart for the ware and Britain sued for peace. The American Revolution was won.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services