William H. Taft Seeks Justice in the Well Known Case of an African American Doctor Tarred and Feathered in Vicksburg

A seething Taft calls the violence against Dr. John Miller, a graduate of Howard University and Williams College, an “outrage", and calls for the Solicitor General to investigate

In an unpublished letter to Williams College’s President: “If they [African Americans] are to be subjected to such an outrage as this, the hope of helping the South by strengthening the industrial and moral qualities and virtues of the negro is hopeless”

In 1918, 47 year old African American Dr. John A....

Explore & Discover

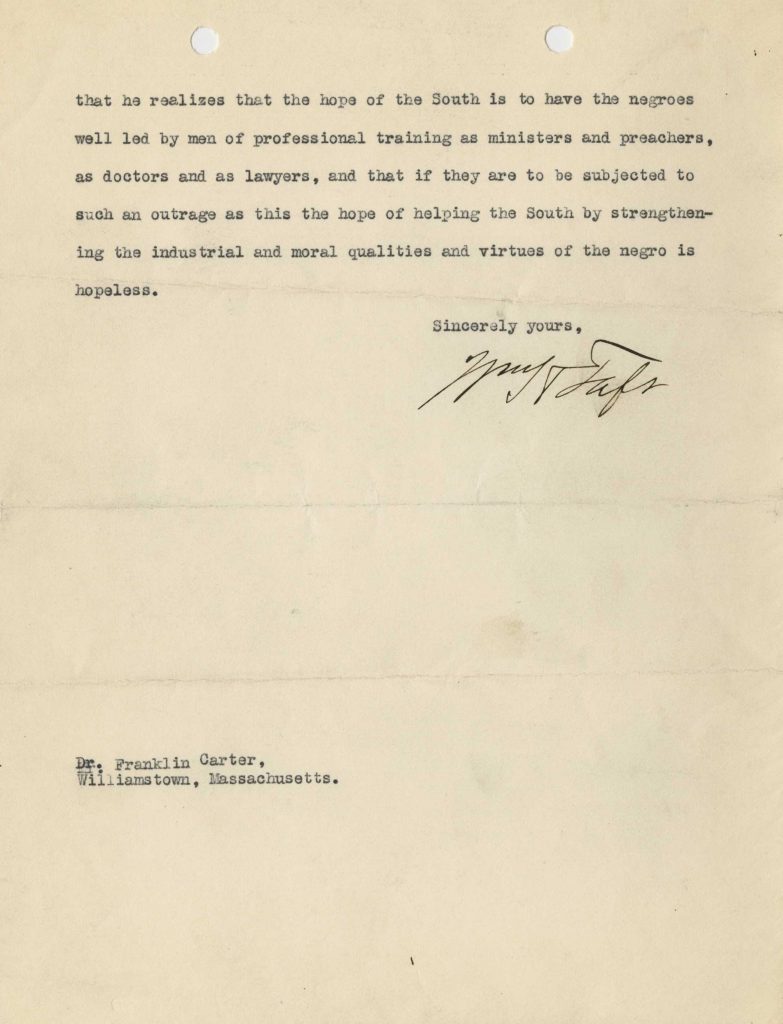

- The Signature - A closeup on Taft's bold signature at the end of his powerful letter

- Williams College - This letter is addressed to the President of Williams College, where the African American man attended

- Racial relations - Taft attributes the hate of these white men to jealousy of the growing wealth and education of the black community

- Powerful language - Taft is so incensed that he says this story caused him the bitterest indignation

In an unpublished letter to Williams College’s President: “If they [African Americans] are to be subjected to such an outrage as this, the hope of helping the South by strengthening the industrial and moral qualities and virtues of the negro is hopeless”

In 1918, 47 year old African American Dr. John A. Miller had lived in Vickburg for almost two decades. A native of Virginia, he attended the preparatory school at Howard University and earned degrees from William College in 1896 and the University of Michigan’s Medical School in 1900. Dr. Miller was at the turn of the century among the most prominent black men in Mississippi, and indeed in the country. A professional man highly educated in elite northern institutions, a native southerner yet not a native of his resident city or state, Miller epitomized the difficulty of defining racial boundaries.

During World War I, people in all walks of life were prevailed upon to buy war bonds and savings stamps. The Vicksburg War Stamp Savings Committee organized a sales campaign led by George Williamson, cashier of the city’s largest bank. The committee resorted to highly coercive tactics, threatening that anyone who refused to pledge the amount determined by an “Allotment Committee” would put themselves “in line for a yellow card’ – a public display reserved for “pledge slackers.’ The campaign came to a climax on “War Savings Day,” 28 June 1918, and in the week leading up to that date, local police arrested and fined a British citizen for “acting in a discourteous manner,” to members of the stamp committee. They charged a black man, Sam Gaithers, with “interfering with a government loan” for telling his nephew “that he did not have to buy any of the stamps if he didn’t want to.”

It was in this charged atmosphere that, sometime in the Spring or early summer of 1918, John Hennessey of the War Savings Committee visited Dr. Miller and asked him to subscribe to war bonds. His tart reply, that whites had “crushed” the patriotism of African Americans, and that Hennessey should “think over what I have said, and come back, and I will tell you how many bonds I am going to buy,” set off the chain of events that led eventually to Miller’s being dragged out of his home into the public square, and then tarred and feathered on the city’s streets on July 23.

Franklin Carter was a long time President of Williams College, where Dr. Miller had studied. He wrote to friend, former President (and future Supreme Court Chief Justice) William Howard Taft, seeking justice for Dr. Miller. This is Taft’s outraged response, and his demand that prosecutions be brought for this.

Typed letter signed, on his personal letterhead, New Haven, February 10, 1919, to “My dear President Carter.” “I have read the affidavit of Doctor Miller, and his account of the outrages committed by the officials of the town of Vicksburg upon him arouse in me the bitterest indignation. I would like to cross examine him as to what he had said in public on the subject of the war, and what it was that aroused the peculiar indignation of these white officials against him. His description of his dress, his diamond sleeve-buttons and his automobile would suggest a possibility of jealousy of his property, an assumption of greater wealth than he had and a resentment against a negro that he should be more thrifty and prosperous than a white. I would like to know whether he had made any speeches or any remarks which might have been reported in the press or which could have come to the ears of those engaged in pressing subscriptions to the War Savings Stamps which would have created such a dreadful and cruel spirit. The Solicitor General, at present Acting Attorney General, is a very able lawyer from Atlanta whom I have known for many years. I enclose a letter to him which you are at liberty to send to him requesting that he take steps to investigate this outrage. I believe him to be a high minded man, with broader vision than many in the South, and that he realized that the hope of the South is to have the negroes led by men of professional training as ministers and preaches, as doctors and lawyers, and that if they are to be subjected to such an outrage as this the hope of helping the South by strengthening the industrial and moral qualities and virtues of the negro is hopeless.”

This famous case demonstrated the racial tensions imposed by the war in the South.

We obtained this letter from a Carter descendant, and it has never before been offered for sale.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services