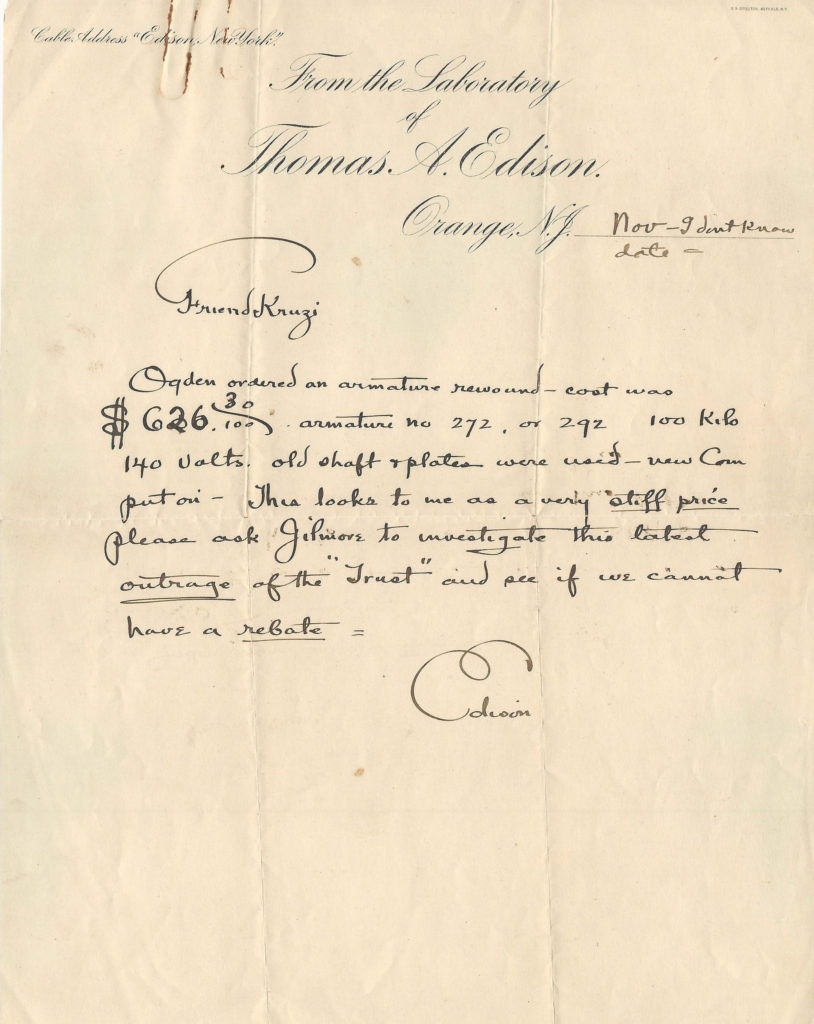

Thomas Edison Feels That the Newly Formed General Electric, Under J.P. Morgan, Is Overcharging Him for His Lighting and Motor Supplies

He derisively refers to GE as the “Trust” and wants a refund on fixing a generator that was lighting his plant in Ogden

The Edison General Electric Company was incorporated on April 24, 1889, to merge Edison’s various business interests. Financiers J.P. Morgan and Anthony Drexel were involved in the formation. Edison himself was not involved day-to-day with the company. Meanwhile the war of the currents was raging to determine who would service the growing...

The Edison General Electric Company was incorporated on April 24, 1889, to merge Edison’s various business interests. Financiers J.P. Morgan and Anthony Drexel were involved in the formation. Edison himself was not involved day-to-day with the company. Meanwhile the war of the currents was raging to determine who would service the growing electrical market. Edison president Henry Villard, who had engineered the merger that formed Edison General Electric, was working on the idea of merging that company with Thomson-Houston or Westinghouse. He saw a real opportunity in 1891. The market was in a general downturn causing cash shortages for all the companies concerned, and Villard was in talks with Thomson-Houston, which was Edison General Electric’s biggest competitor. Patent conflicts were stymieing the growth of both companies and the idea of saving on some 60 ongoing lawsuits as well as avoiding the losses inherent in trying to undercut each other by selling generating plants below cost pushed forward the idea of this merger in financial circles. A financial merger would obviate that.

Edison hated the idea and tried to hold it off, but Villard thought his company, now winning its incandescent light patent lawsuits in the courts, was in a position to dictate the terms of any merger. As a committee of financiers, which included J.P. Morgan, worked on the deal in early 1892 things went against Villard. In Morgan’s view, Thomson-Houston looked on the books to be the stronger of the two companies, and he engineered a behind the scenes deal announced on April 15, 1892 that put the management of Thomson-Houston in control of the new company, now called General Electric (dropping Edison’s name). Thomas Edison was not aware of the deal until the day before it happened. The fifteen electric companies that existed 5 years before had merged down to two: General Electric and Westinghouse. The war of currents came to an end, and this merger of the Edison company, along with its lighting and DC current patents, and Thomson-Houston, with its AC patents, created a company that controlled three quarters of the US electrical business. Privately Edison was bitter that his company and all of his patents had been turned over to the competition.

John Kruesi had been apprenticed as a locksmith in Switzerland, and migrated to the United States where he settled in Newark, New Jersey. There he met Thomas Edison, who was impressed with the young Swiss immigrant and took a liking to him, employing him in his workshop starting in 1872. He became Edison’s head machinist through his Newark and Menlo Park periods, responsible for translating Edison’s numerous rough sketches into working devices. Since constructing and testing models was central to Edison’s method of inventing, Kruesi’s skill in doing this was critical to Edison’s success as an inventor.

William E. Gilmore was the man behind the Edison Manufacturing Company, a tough and frequently bullish character who had as great an influence as any on the nascent American film industry. Gilmore was appointed vice president and general manager of the Edison Manufacturing Company on 1 April 1894, taking over from Alfred O. Tate.

Edison had invented a motor that ran his operations at Ogdensburg, NJ, and this was powered by another of his inventions: an armature. These had to be re-serviced, evidently an operation that his former entity did. He sent this armature off to the Morgan-controlled entity.

Autograph letter signed, November 1894, on his Orange, NJ letterhead, to “Friend Kruezi.” “Ogden [another facility] ordered an armature rewound – cost was 626.30. Armature no 272, or 292, 100 kilo 140 volts, old shaft and plates were used – new Com put on. This looks to me as a very stiff price. Please ask Gilmore to investigate this latest outrage of the ‘Trust’ and see if we cannot have a rebate.”

We acquired this directly from a Kruesi descendant, and it has never before before been offered for sale. It is interesting to note that no letters from Edison to Kruesi whatever have reached the public sale market in at least 40 years, nor can we recall seeing any.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services