George Washington and Benedict Arnold – Incredibly Rare Signed Free Frank From the Hero of the Revolution to Its Villain

One of just two Washington-to-Arnold autographs we have ever seen in our decades in the field.

Benedict Arnold’s role as a prominent merchant shipper brought him into direct conflict with the British during the Stamp Act and the Townsend Acts controversies. Arnold joined the Sons of Liberty. When the Revolution broke out, he was elected captain in the Connecticut militia, and with his unit participated in the siege...

Benedict Arnold’s role as a prominent merchant shipper brought him into direct conflict with the British during the Stamp Act and the Townsend Acts controversies. Arnold joined the Sons of Liberty. When the Revolution broke out, he was elected captain in the Connecticut militia, and with his unit participated in the siege of Boston. He had the idea of capturing Fort Ticonderoga, and promoted to Colonel participated in the taking of that fort. When Congress determined to invade Canada and attack Quebec, he was passed over for command of the expedition, which went to Richard Montgomery. During the failed attack, Montgomery was killed and Arnold received a leg wound. He was promoted to brigadier general for his role in reaching Quebec. Arnold then traveled to Montreal, where he served as military commander of the city until forced to retreat by an advancing British army. He presided over the rear of the Continental Army during its retreat, then directed the construction of a fleet to defend Lake Champlain. During these actions, Arnold made a number of friends, including Gen. George Washington, but also a large number of enemies within the army power structure and in Congress.

In February 1777, he learned that he had been passed over for promotion to major general by Congress. Washington stuck up for him, refused his offer to resign, and wrote to members of Congress in an attempt to correct this, noting that “two or three other very good officers” might be lost if they persisted in making politically motivated promotions. Arnold then led a contingent of militia attempting to stop or slow the British return to the New England coast, and was again wounded in his left leg at Ridgefield. He continued on to Philadelphia, where he met with members of Congress about his rank. His action at Ridgefield, coupled with Washington’s letter, resulted in Arnold’s promotion to major general, although his seniority was not restored over those who had been promoted before him. Amid negotiations over that issue, Arnold wrote out a letter of resignation on July 11. Washington refused his resignation and ordered him north to assist with the defense there. Soon after Arnold distinguished himself in the Battle of Saratoga, where he was again wounded in his left leg. In response to Arnold’s valor at Saratoga, Congress restored his command seniority. However, Arnold interpreted the manner in which they did so as an act of sympathy for his wounds, and not an apology or recognition that they were righting a wrong.

After the British withdrew from Philadelphia in June 1778, Washington appointed Arnold military commander of the city. He arrived on June 19, 1778. Arnold lived extravagantly in Philadelphia, and was a prominent figure on the social scene. He married the daughter of a noted loyalist. Arnold was also trying to capitalize financially on the change in power there, engaging in a variety of business deals designed to profit from war-related supply movements and benefiting from the protection of his authority. These schemes were sometimes frustrated by powerful local politicians, who eventually amassed enough evidence to publicly air charges against him. Arnold demanded a court martial to clear the charges, writing to Washington in May 1779, “Having become a cripple in the service of my country, I little expected to meet [such] ungrateful returns”.

In 1779 Arnold was court martialled, charged with 13 counts of misbehavior, including misusing government wagons and illegally buying and selling goods. Although Arnold was cleared of most charges, Washington issued a reprimand against him, which made Arnold increasingly angered. Washington wrote: “The Commander-in-Chief would have been much happier in an occasion of bestowing commendations on an officer who had rendered such distinguished services to his country as Major General Arnold; but in the present case, a sense of duty and a regard to candor oblige him to declare that he considers his conduct [in the convicted actions] as imprudent and improper.” So Washington, too, had turned against him.

As early as 1778 there were signs that Arnold was unhappy with his situation and pessimistic about the country’s future. On November 10, 1778, General Nathanael Greene wrote, “I am told General Arnold is become very unpopular among you owing to his associating too much with the Tories.” A few days later, Greene received a letter from Arnold, where Arnold lamented over the “deplorable” and “horrid” situation of the country at that particular moment, citing the depreciating currency, disaffection of the army, and internal fighting in Congress for the country’s problems, while predicting “impending ruin” if things would not soon change. In May 1779 he opened channels to the British, and by July was providing the British with troop locations and strengths, as well as the locations of supply depots, all the while negotiating with them over his compensation. By October 1779, the negotiations had ground to a halt.

Arnold resigned his post in Philadelphia in April 1780. In August he gained command at West Point, where he entered into negotiations with the British to surrender that place. He transferred money to British forces and passed on information that would aid the British in capturing West Point, while weakening the fort’s defenses and thinning out its supplies. John Andre, Arnold’s British contact, was captured and ultimately executed for his role in the plot. Arnold narrowly avoided capture by the Americans and eventually fled to England. Arnold served in the British army for the duration of the war, and then engaged in business in Canada and England until his death in 1801. Since then, his name has become synonymous with traitor.

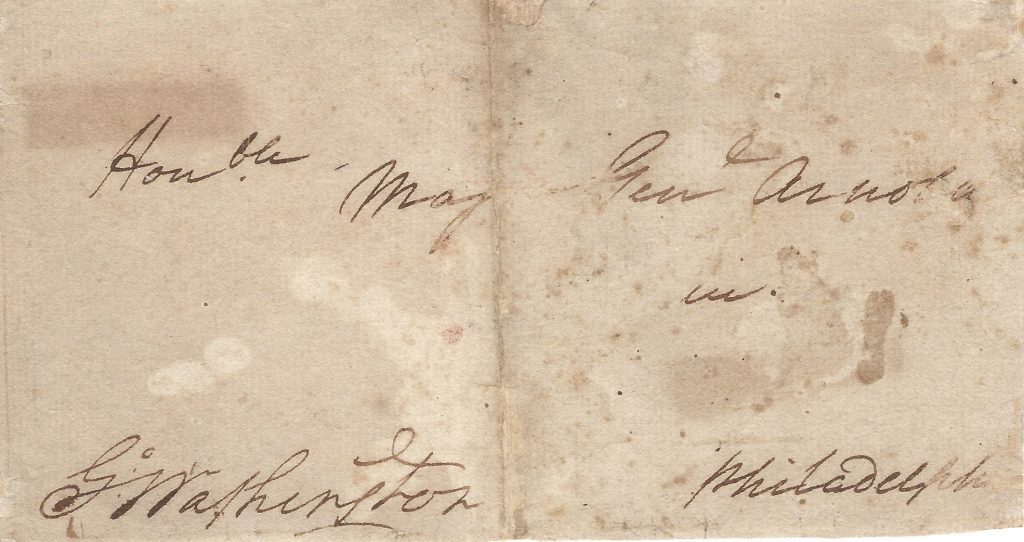

Free franked address panel addressed in the hand of James McHenry to “Honorable Maj. Genl. Arnold in Philadelphia”, signed by George Washington as Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army. We can date the letter this accompanied to June 19, 1778 to April 1780, when Arnold was in command of Philadelphia. This is just the second George Washington autograph to Benedict Arnold that we have ever seen, and our research discloses that other being the only one that has reached the public marketplace in the past forty years. The other was a letter with faded handwriting with significant enough damage to require restoration, making this perhaps the best Washington signature to Arnold offered in all those decades.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services