An Extremely Rare Executive Order Signed by President Abraham Lincoln, a Controversial One, Permitting the Export of Cotton from the South

President Lincoln saw getting cotton to Europe as a foreign policy goal, and also as a way to build a bridge between the economies of North and South and ease the path toward reconstruction

He orders approval of a lucrative cotton sale contract granted to Robert Lamon, brother of Lincoln’s friend and bodyguard Ward Hill Lamon

But the granting of cotton contracts to well-connected people became a cause celebre, for which Lincoln was criticized, and led to a congressional investigation

https://cdn.raabcollection.com/wp-content/uploads/20231204130534/Lincoln-cotton-Youtube-Embed-1-2.mp4

When Abraham Lincoln...

He orders approval of a lucrative cotton sale contract granted to Robert Lamon, brother of Lincoln’s friend and bodyguard Ward Hill Lamon

But the granting of cotton contracts to well-connected people became a cause celebre, for which Lincoln was criticized, and led to a congressional investigation

When Abraham Lincoln was elected President in 1860, he insisted that Ward Hill Lamon accompany him to the nation’s capitol. Lamon not only became Lincoln’s confidant, but also his personal bodyguard. He was also named U.S. Marshal for the District of Columbia. Lamon had been a law partner of Lincoln’s in Danville, Illinois, and Lincoln maintained a close friendship throughout the 1850s. Lamon worked diligently in all of his friend Lincoln’s political campaigns. Many of the stump debates could become contentious and Lamon was always on hand to come to Lincoln’s aide, if needed. Ward Hill Lamon was 18 years younger than Lincoln and this youth served the President as not just a guardian, but also as a relief from the daily stress and pressures of the civil conflict. The burdens of the political intrigues of Washington’s power elite cast Lamon into unchartered waters, and he also needed a trusted friend and advisor: he chose his brother Robert Lamon.

Robert was appointed a clerk and Deputy U.S. Marshal, serving under his brother, and charged with maintaining the records and detainees of the District’s jail and protecting the life of President Lincoln. He was seen as a surrogate for his brother, who was not popular with some in Lincoln’s cabinet. Secretary of State William Seward removed the jail from the U.S. Marshal’s sphere of authority, reducing Lamon’s salary. Ward tendered his resignation, which Lincoln refused.

In December of 1864, U.S. Marshal Ward Hill Lamon petitioned for a Cotton Delivery contract for his brother Robert Lamon. The contract was authorized and endorsed by President Lincoln in an Executive Order.

With the blockade of the Confederacy in 1861, goods in control of the South ceased to be able to leave for northern ports for overseas markets. The South’s chief export was cotton, and a shortage of cotton developed in manufacturing hubs in Great Britain and France. The British were then the world’s manufacturing powerhouse, with their mills creating clothing for the world. The shortage of cotton increased its value to unheard of amounts. In August 1862, Congress authorized the taking of property, including cotton, belonging to civil and military officers of the Confederacy, or to any persons who had given aid and comfort to the rebellion. As Federal lines were extended, more and more plantations came under Union control, including buildings, live stock, and especially cotton. These were often either found without a visible owner, or were owned by Confederate sympathizers; and this property was escheated to the U.S. government, to use or allow others to use as it decided.

Also in 1862, the federal government also created a system of permits or contracts with authorization, administered by the Treasury, that allowed loyal owners of cotton to sell it. Lincoln wanted such a system to prevent any trader or group of traders from monopolizing the trade; he insisted that the trade be open to all loyal citizens. To insure that the trade was open and fair, a Treasury agent had to investigate the loyalty of the applicant (and whether the applicant truly owned or controlled cotton in the South) before granting a contract or approving a permit. The Treasury agents often followed in the wake of the armies, and sometimes went ahead of them. Competing with government agents were a virtual army of private northern businessmen, all seeking to get their hands on this cotton, lawful or not. Although the permitting system seemed well designed, its integrity depended upon the honesty and diligence of the Treasury agents. The agents needed to be pillars of rectitude to withstand the blandishments and bribes of prospective traders. Seeing an opportunity, prominent administration officials, politicians, and businessmen lobbied to have their associates appointed Treasury agents, and, in return for these political favors, agents no doubt displayed favoritism in approving some contracts or permits or in granting approval rapidly. President Lincoln saw getting cotton to Europe, and the foreign policy gains that would flow from it, as his main aim. His policy regarding Treasury Agent authorized requests was to approve them if possible. Something else was on Lincoln’s mind late in the war. He felt the resumption of this trade important and wanted to find a way for the government to be able to buy cotton that was legitimately acquired. Historian Gabor Boritt makes the argument that his use of a policy allowing, under strict controls, cross-border trade in cotton, allowed him to build a bridge between the economies of North and South and ease the path toward reconstruction.

Some agents, including perhaps the most notable one, Hanson Alexander Risley, a friend of Secretary of State William Seward, were lax in enforcing the regulations, often not checking whether prospective traders actually controlled or yet owned cotton in the South. Many of the license seekers chose to misrepresent their ownership or control, preferring to get the permit and then find cotton “to own or control.” In some cases, the applications were questionable. By late 1864, the property in federal hands or potentially so was large, and in anticipation of the end of the war, the markets began to discount the value of cotton. So there developed a race against time. Risley vetted Lincoln’s friend Leonard Swett, who received three permits/contracts in December 1864 for a combined 150,000 bales of cotton. These covered cotton in every state of the Confederacy except Virginia and North Carolina. Risley also vetted Robert Hill, brother of Lincoln’s bodyguard, Ward Hill Lamon of Illinois, who received permits for a total of 50,000 bales of cotton, also widely scattered throughout the Confederacy. How Lamon and Swett, who had never dealt in cotton before, could possibly control large amounts of cotton was apparently never questioned. New York’s kingmaker Thurlow Weed, whom Lincoln needed as an ally, also vouched for some prospective traders. During a three month period at the end of 1864 and beginning of 1865, the enthusiastic Risley issued permits/contracts to traders covering over 900,000 bales of cotton. Men recommended by the President or Thurlow Weed controlled the vast majority of these bales. Lincoln seems to have approved most if not all of the requests made by his associates. In fact, Risley approved southerner Samuel Noble’s application because he was accompanied by Ward Lamon and he possessed a references from President Lincoln himself.

This is one of Lamon’s original authorizations to Robert Lamon. Delivery contract with permit signed, Washington, December 27, 1864. “I Hanson A. Risley, agent for the purchase of products of the insurrectionary states, on behalf of the Government of the United States, at Norfolk, Va., hereby certify that I have agreed to purchase from Robert Lamon five thousand bales of cotton, which product it is represented are or will be at or nearby the national military lines within the States of Louisiana, Alabama, Mississippi, and Texas, on or before the first of June 1865, and which he stipulates will be delivered to O.N. Cutler at New Orleans, unless he is prevented from doing so by the authority of the United States.

“I therefore request safe conduct for the same Robert Lamon, his agent, and his means of transportation and said products from such points in or near the national military lines, to New Orleans where the products so transported are to be sold and delivered to said O.N. Cutler, agent etc. under the stipulation referred to above and pursuant to regulations prescribed by the Secretary of the Treasury.” It is signed by Risley as special agent.

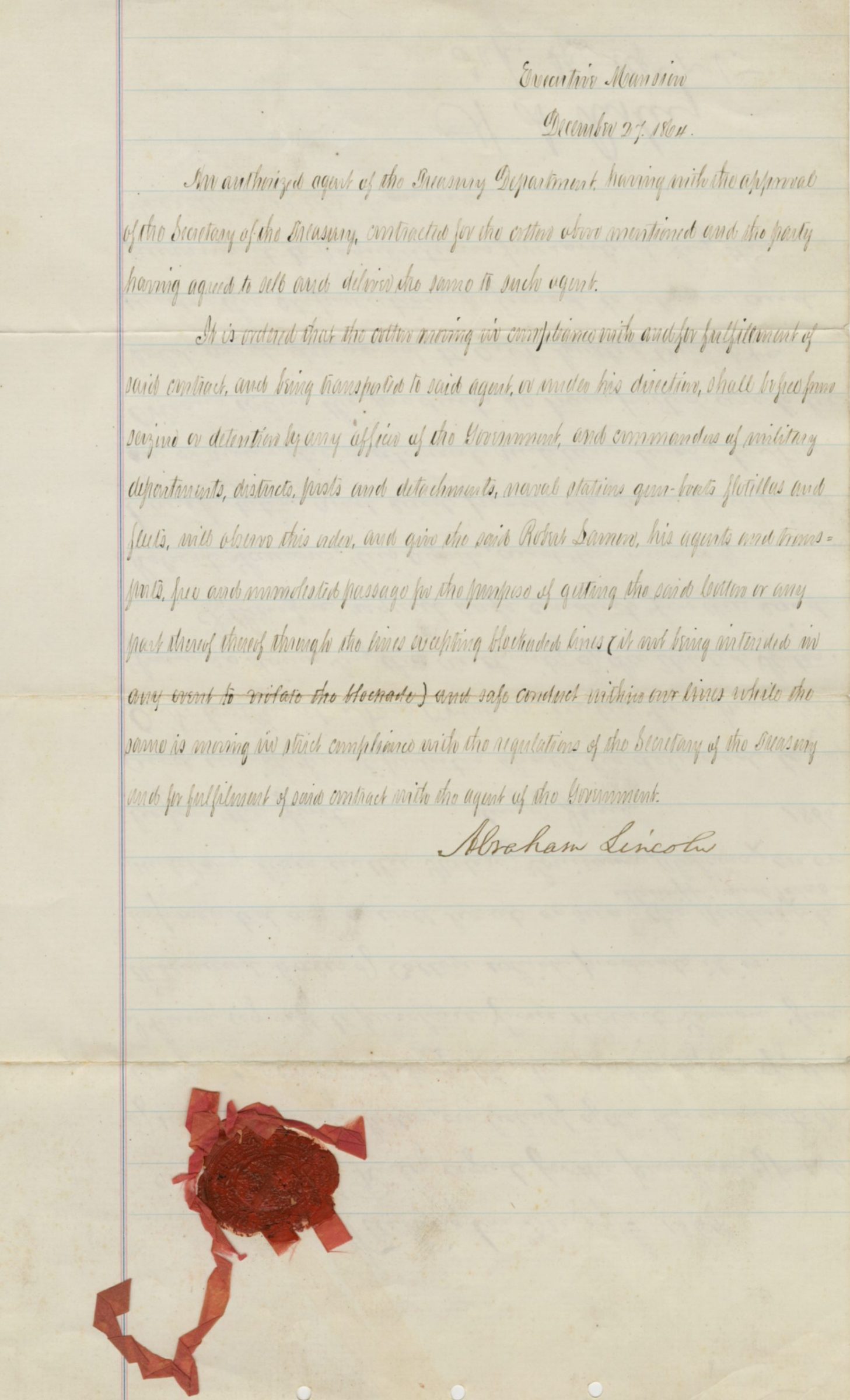

Lincoln gave this his approval. Executive order signed, Executive Mansion, Washington, December 27, 1864. “An authorized agent of the Treasury Department having with the approval of the Secretary of the Treasury, contracted for the cotton above-mentioned, and the party having agreed to sell and deliver the same to such agent.

“It is ordered that the cotton moving in compliance with and for fulfillment of said contract, and being transported to said agent, or under his direction, shall be free from seizure or detention by any officer of the Government, and commanders of military departments, districts, posts and detachments, naval stations, gun-boat flotillas and fleets, will observe this order, and give the said Robert Lamon, his agents, and transports, free and unmolested passage for the purpose of getting the said cotton or any part thereof through the lines excepting blockade lines (it not being intended in any event to violate the blockade), and safe conduct within our lines, while the same is moving in strict compliance with the regulations of the Secretary of the Treasury, and for fulfillment of said contract with the agent of the Government.” It is signed “Abraham Lincoln”, and has the red seal at lower left. Some historians feel that Lamons were being compensated in this way for the loss of revenue they had suffered when Secretary of State William Seward – a Risley friend – removed the jail from the U.S. Marshal’s sphere of authority, thus reducing Lamon’s salary.

As the granting of contracts to well-connected people became known, it became a cause celebre. It was headline news, and generated a congressional investigation.

This is a great rarity, and just our second such Executive Order signed by Abraham Lincoln in all these decades. Until now, it has for many years been in one of the nation’s foremost private collections. Moreover, a search of public sale records going back forty years reveals no such executive orders, which are technically such orders. Neither are cotton sales authorizations under the Treasury signed by Lincoln, in any form, common.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services