The Trail of Tears Begins: President Andrew Jackson Sends the Senate Confidential Documents on the First Indian Removal Treaty

This document was held and read aloud in a chamber that included Daniel Webster, John Tyler

We have never before seen a letter of Jackson to Congress on the market

That Treaty was with the Choctaws, thousands of whom died as they gave up their ancestral lands and went west to Indian Territory

“Since my message of the 20th December last, transmitting to the Senate a...

We have never before seen a letter of Jackson to Congress on the market

That Treaty was with the Choctaws, thousands of whom died as they gave up their ancestral lands and went west to Indian Territory

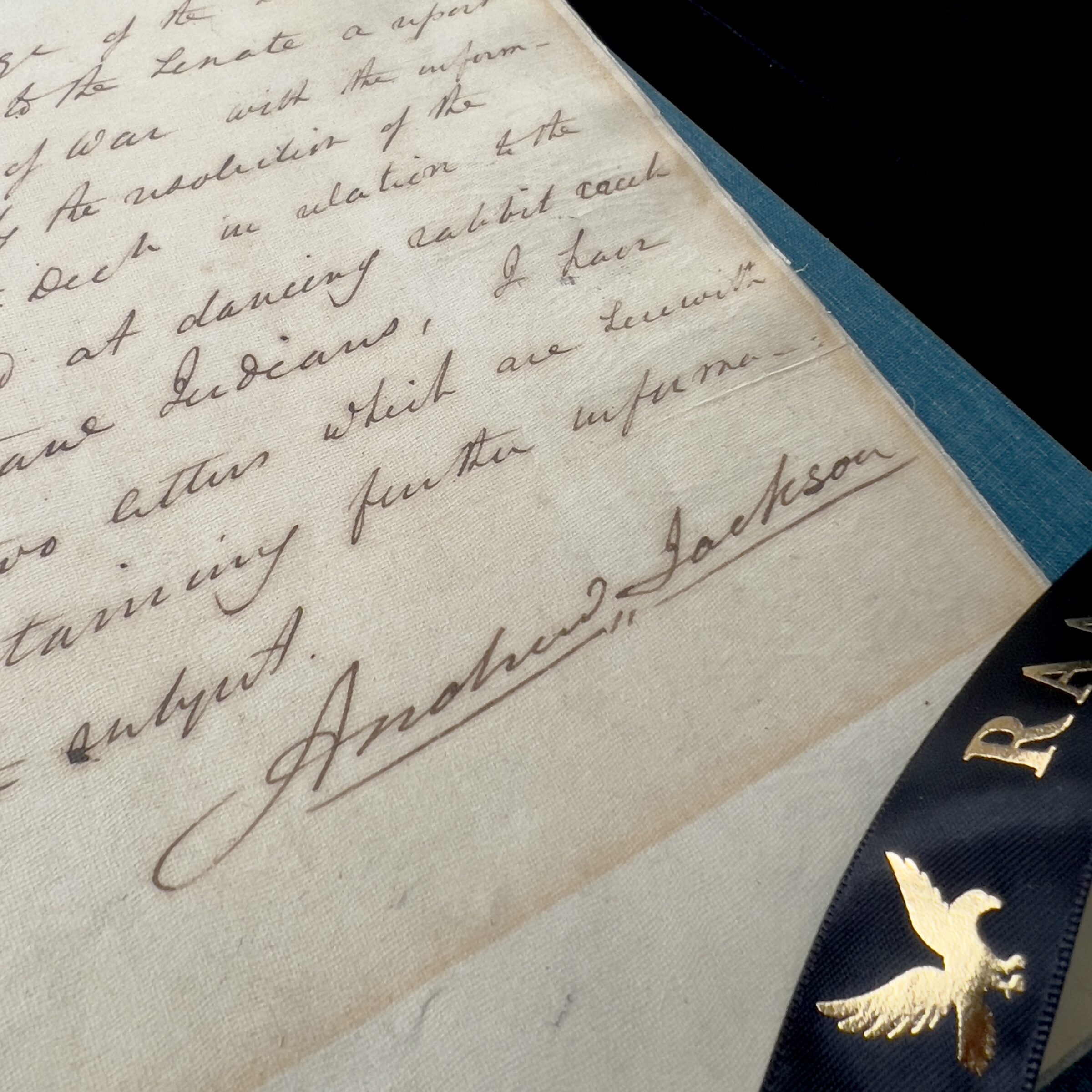

“Since my message of the 20th December last, transmitting to the Senate a report of the Secretary of War with the information requested by the resolution of the Senate of the 14th December in relation to the Treaty concluded at Dancing Rabbit Creek with the Choctaw Indians, I have received the two letters which are herewith enclosed contain further information on the subject.”

This is only the second document we have ever had relating to the deadly Indian Removal and Andrew Jackson’s role in it

The Choctaw Trail of Tears was the relocation by the United States government of the Choctaw Nation from their own homelands, in Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana, and particularly Mississippi, to lands west of the Mississippi River in Indian Territory (now Oklahoma). Pressure by Americans to clear these lands to make it possible for new American settlers to claim them had been building for years.

The election of Andrew Jackson as U.S. president in 1828 forever altered the relationship between Americans and the native people living east of the Mississippi River. It brought pressure for these people to uproot themselves, and settle west of the Mississippi River in Indian Territory. Even before Jackson was inaugurated in March 1829, the Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi legislatures passed laws extending state jurisdiction over all lands within their borders, knowing that they would now have an ally in the White House. The 1828 election also brought Democratic Party domination to the national government and with it widespread support for Indian Removal. Southern state “extension laws,” as they were known, outlawed native governments, forbade communal land holdings, and declared that native people were state citizens. When Jackson took office, he urged southern natives to remove voluntarily while simultaneously supporting legislation to enact removal. Because of the state actions, Jackson was able to cast the Indian removal policy as necessary to solve the “constitutional crisis” over whether the states or the federal government held jurisdiction over Indian affairs.

The Indian Removal Act became law on May 28, 1830. It authorized the president to appoint commissioners to meet with each eastern native tribe to set conditions for giving up title to their existing land in exchange for lands in Indian Territory. The Choctaws were the first group to negotiate such a treaty.

On September 15, 1830, just months after the Indian Removal Act, the Choctaws met with U.S. commissioners Secretary of War John Eaton and Jackson’s long-time friend and Tennessee militia general John Coffee at Dancing Rabbit Creek in present-day Noxubbee County, Mississippi. In a carnival-like atmosphere, the U.S. officials explained the policy of removal through interpreters to an audience of 6,000 men, women and children. The Choctaws faced migration west of the Mississippi River or submitting to U.S. and state law as citizens. The treaty would sign away the natives’ traditional homeland to the United States. Twice the chiefs rejected the terms because a group of seven women elders (who sat front-and-center at the negotiations) refused to permit the sale of any of their ancestral lands. Under the matrilineal society of the Choctaws, women traditionally controlled access to and governance of land and families.

Furious, Eaton and Coffee called off the negotiations and instead met secretly with Choctaw chiefs Greenwood Leflore, Mushulatubbee, and others to produce a treaty on which they could agree. Included in this new document was an article which allowed those Choctaw who chose to remain in Mississippi to become the first major non-European ethnic group to gain recognition as U.S. citizens. Specifically, individual Choctaw men and their families could claim title to specific allotments of land in Mississippi on which they could then live as state citizens or sell and use the proceeds to fund their move to the west. An additional supplement to the original treaty also authorized extra allotments of land to those chiefs who signed the treaty and their family members, to other pro-Removal Choctaws, and to traders to whom the Choctaws were indebted. The treaty ceded about 11 million acres of the Choctaw Nation in what is now Mississippi in exchange for about 15 million acres in the Indian Territory.

The Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek was concluded, and was signed by the chiefs and U.S. diplomats on September 27, 1830, and Jackson officially notified Congress in December. It was ratified by the U.S. Senate on February 25, 1831. This treaty was the first removal treaty which was carried into effect under the Indian Removal Act, and one of the largest land transfers ever signed between the United States Government and Native Americans in time of peace. Around 15,000 Choctaws with 1,000 slaves travelled by wagon, on horseback, by boat, and on foot over the next few years, experiencing much hardship and death along the way. This, then, was the start of what we call today the Trail of Tears. The population transfer occurred in three migrations during the 1831–33 period. About 2,500 Choctaw died along the way. Approximately 5,000–6,000 Choctaws managed to remain in Mississippi.

Letter signed, Washington, January 3, 1830 [actually 1831], “To the Senate of the United States”, providing the Senate with additional information on the Treaty as it considered ratification. “Since my message of the 20th December last, transmitting to the Senate a report of the Secretary of War with the information requested by the resolution of the Senate of the 14th December in relation to the Treaty concluded at Dancing Rabbit Creek with the Choctaw Indians, I have received the two letters which are herewith enclosed contain further information on the subject.” Lightly silked.

Contemporary accounts note that the contents were read aloud but then referred to the Committee on Indian Affairs “under the injunction of secrecy.”

The message Jackson sent on 20th December stated: “To the Senate of the United States. In compliance with the resolution of the Senate of the 14th instant calling for copies of any letters or other communications which may have been received at the Department of War from the chiefs and head men or any of them of the Choctaw tribe of Indians since the treaty entered into by the commissioners on the part of the United States with that tribe of Indians at Dancing Rabbit Creek and also for in formation showing the number of Indians belonging to that tribe who have emigrated to the country west of the Mississippi etc. etc. I submit herewith a report from the Secretary of War containing the information requested.”

Thus in this message of January 3, Jackson was either providing correspondence from the native chiefs or on their migration.

This is only the second document we have ever had relating to the deadly Indian Removal and Andrew Jackson’s role in it.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services