A Window Into the Glittering Opulence of the Renaissance Courts of Italy and Spain: A Miniature of St Martin and the Beggar from the Manuscript Collectar of Francesco Maria II Della Rovere, Duke of Urbino, By the 16th Century Master-artist Simonzio Lupi da Bergamo

This work once adorned the walls of a Florentine palace alongside numerous treasures now in the sublime Uffizi gallery in Florence

Ten other leaves from the manuscript are in the Galleria Palatina in Palazzo Pitti, and others can be found in British Library (Add MS 46365B), Valencia, Museo de Bellas Artes de san Pío, Hartford, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Princeton University Art Museum (their y1940-420), with others in a private Italian art...

Ten other leaves from the manuscript are in the Galleria Palatina in Palazzo Pitti, and others can be found in British Library (Add MS 46365B), Valencia, Museo de Bellas Artes de san Pío, Hartford, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Princeton University Art Museum (their y1940-420), with others in a private Italian art collection.

Francesco Maria II Della Rovere was the last secular nobleman to hold the title of duke of Urbino, and lived at the heart of two of the most wealthy courts of the European Renaissance. He was born in 1549 in Pesaro (the seafront palace of the dukes of Urbino, and later the capital of the duchy) and as a teenager was sent to the court of Philip II of Spain – a son of the Habsburg Emperor Charles V, and the ruler of Spain, Portugal, Naples and Sicily, as well as the Seventeen Provinces of The Netherlands, and through his marriage to Mary I of England ruler of that nation as well on paper if not in practice. Supported by the Portuguese spice trade and the rivers of gold and silver from South American mines, Spain reached the peak of its wealth and power.

The young Francesco Maria flourished in this milieu and seems to have intended to stay permanently, announcing plans to marry a Spanish noblewoman. However, his father had other plans, forbade the marriage and ordered him home. On his return home he was married instead to Lucrezia d’Este in 1570, forging a dynastic union with the rulers of nearby Ferrara. His father died four years later, leaving him the dukedom along with substantial debts, and to make matters worse the marriage to Lucrezia remained heirless. He remarried after her death in 1599, but the single child of his second marriage died at the age of eighteen from epilepsy, having fathered only a daughter who could not inherit the dukedom. Francesco Maria was now too old to produce another heir and thus his estates passed to the Pope, ending the medieval dukedom of Urbino. However, while his political life was one of slow and sad collapse, he was a roaring success in his role as art patron. The Spanish court had opened his eyes to the heights of artistic patronage in the Renaissance, and he returned to his family’s own substantial art collection, to energetically add to it. His art collections have been studied recently by Giulia Semenza, in her PhD dissertation ‘Dalla corte roveresca alla Firenze medicea. Un panorama inedito del collezionismo artistico di Francesco Maria II Della Rovere’ (submitted to the University of Rome in 2008-9), and show the duke to be a vigorous rebuilder of the ducal palaces and chapels, and patron to artists including painters, goldsmiths, sculptors and specialist workers in ebony, tooled leather and gem carving, also founding the botteghini in Pesaro – a cluster of workshops modelled after the Medici’s Galleria dei Lavori in Florence – with ten rooms of the ducal palace there given over to artists with different specialisms in each room. These art collections did not pass to the Pope along with the ducal estates, as after the death of Francesco Maria’s son and heir these had already passed to his widow and daughter as part of their dowry and were carried by them back to Florence. Once there, the daughter gave them to the Uffizi – where the centrepiece of that gift is now Piero della Francesca’s celebrated dual portraits of Federico da Montefeltro (1422-1482) and his wife Battista Sforza (1446-1472), Francesco Maria’s ancestors.

The Collectar (a book of collects used in the Holy Office) from which this miniature descends, was written and illuminated for Francesco Maria most probably before he became duke, and passed along with the family’s art collection to Florence and his descendant, Vittoria (for studies of this book see M. Trjulja, ‘I miniatori di Francesco Maria II Della Rovere’, in 1631-1981. Un omaggio ai Della Rovere. Saggi. Schede di opere d’arte restaurate, 1981, pp. 33-38, 77-80; and E. De Laurentiis, ‘La Collezione di “Italian Illuminated Cuttings” della British Library: nuove miniature di Simonzio Lupi da Bergamo, Giovanni Battista Castello il Genovese e Sante Avanzini’, in Il codice miniato in Europa. Libri per la chiesa, per la città, per la corte, 2014, pp. 673-695, as well as the same author’s, ‘Un Giudizio in miniatura. Simonzio Lupi da Bergamo’, Alumina. Pagine miniate 70, 2021, pp. 6-13, noting the present miniature).

Indeed, the artist here, Simonzio Lupi da Bergamo, appears to have worked in the Pesaro court of Francesco Maria in the last quarter of the sixteenth century. Before this, he seems to have worked in Rome, and a letter sent from Francesco Maria to his ambassador in Rome that documents the recruitment of an unnamed illuminator there in 1581 probably refers to him. The parent manuscript of the present cutting predates this, and the artist may have come to the attention of Francesco Maria through this parent-manuscript, later entering his permanent employment in the Botteghini in Pesaro, after he became duke. Records of his employment there exist until 1605, and he probably died then or so soon after.

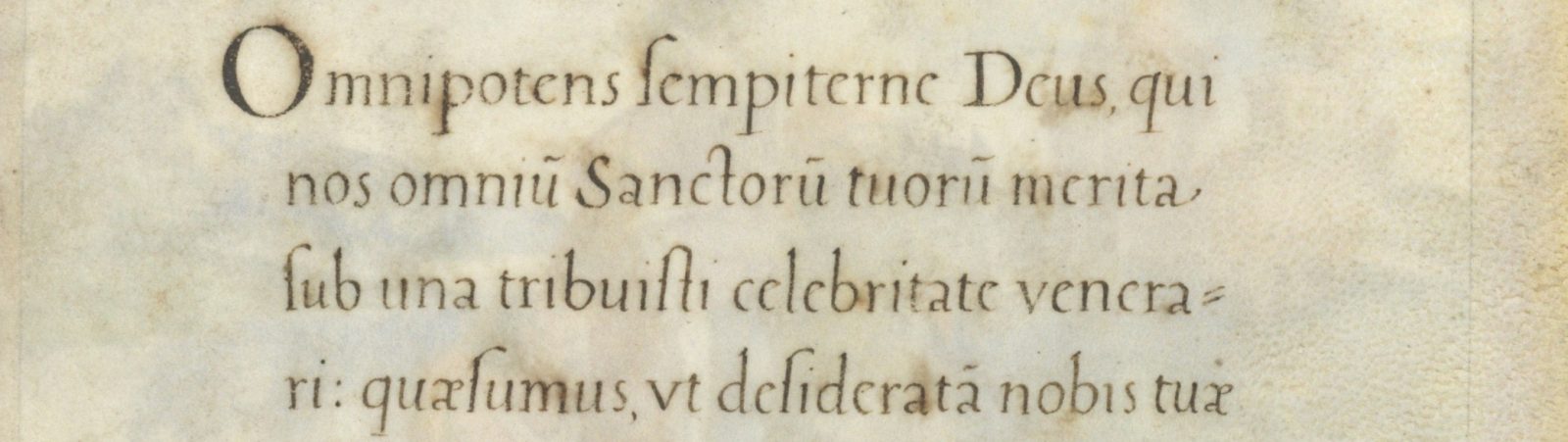

[Italy (Bergamo), c. 1556-75]; Cutting on vellum, 142 x 185mm., the reverse with text for All Saints in a rounded contemporary humanist hand

The Collectar is recognizable in the 1654 inventory of Vittoria’s goods (Archivio di Stato di Firenze, Guardaroba Medicea, 674, fol. 59r), but by the time of the 1692 inventory it had been broken up (ibid., 992, fol. 78). They were presumably gifted away before Vittoria presented the rest of the art collection to the Uffizi.

Ten other leaves from the manuscript are in the Galleria Palatina in Palazzo Pitti, and others can be found in British Library (Add MS 46365B), Valencia, Museo de Bellas Artes de san Pío V (Colección Real Academia de San Carlos, inv. general 372), Hartford, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art (Inv. n. 1920.1032), Princeton University Art Museum (their y1940-420), with others in a private Italian art collection.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services