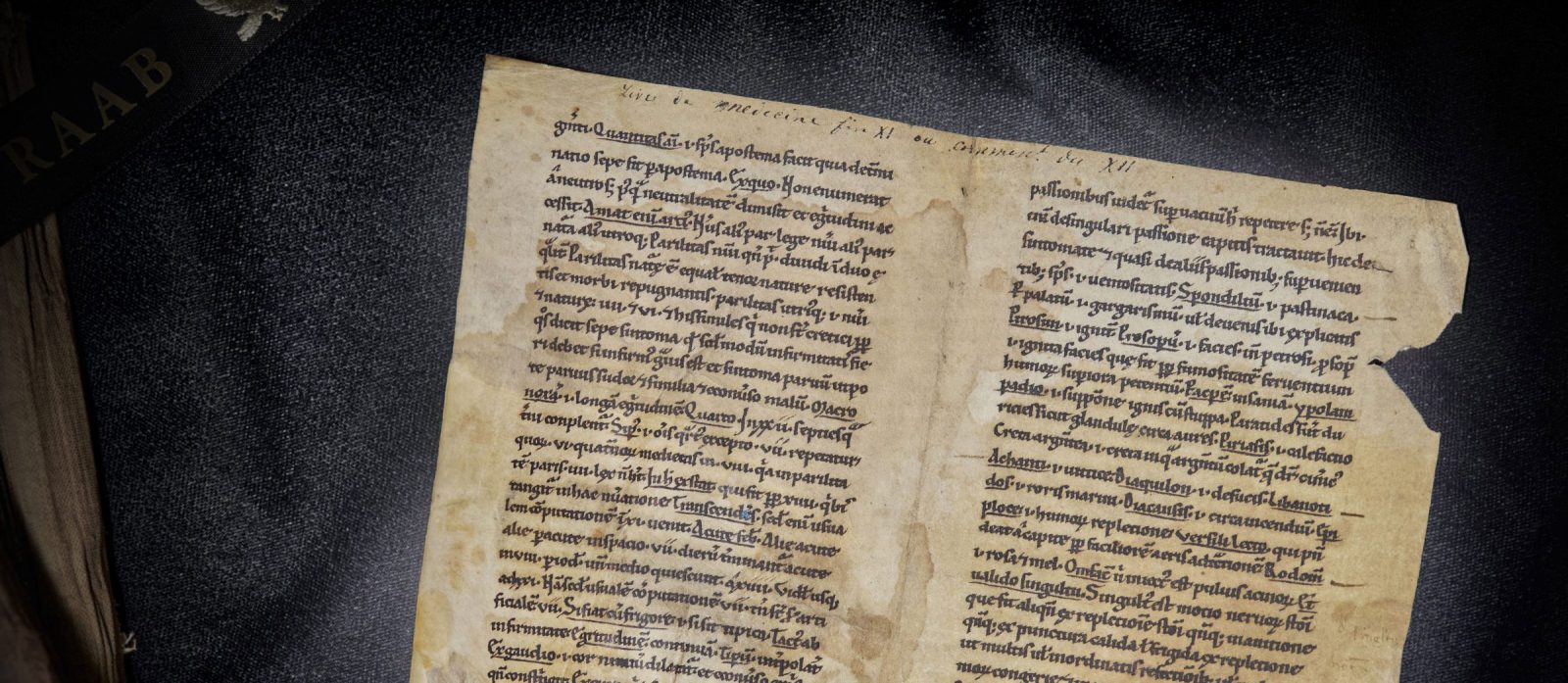

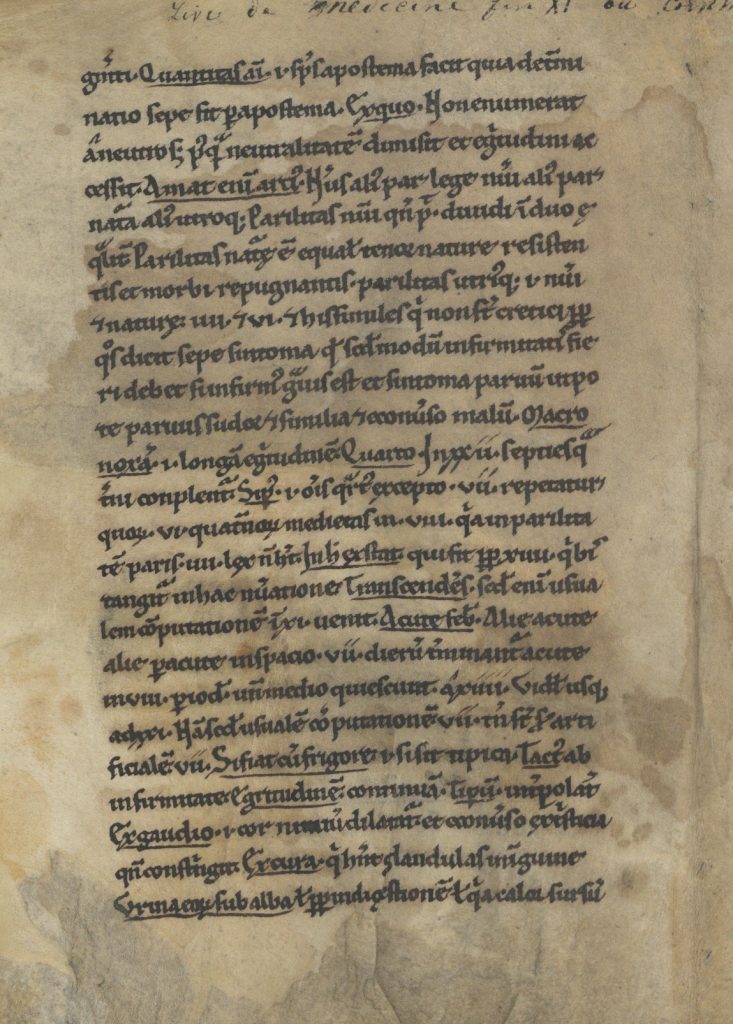

Medicine “De Greco in Latinum”: From a Very Early Medical Work From 12th Century France, Used by Physicians to Understand Newly-Discovered Greek Medical Texts in Their Native Latin

This bifolium stands as a bridge in the transition between medieval and modern medicine

A glance at the document reveals the types of medical complaints medieval physicians were armed to deal with: fevers, spondylitis, apostema (abscesses).

Texts dealing with medicine are relatively rare between the Early Middle Ages and the later part of the High Middle Ages— that is to say between 700 and 1200. During...

A glance at the document reveals the types of medical complaints medieval physicians were armed to deal with: fevers, spondylitis, apostema (abscesses).

Texts dealing with medicine are relatively rare between the Early Middle Ages and the later part of the High Middle Ages— that is to say between 700 and 1200. During this time, medicine was being practiced, but in Europe the practice was transmitted like much of the literature of the time, through oral tradition. So remedies were passed down from one physician to another, or from family member to family member, rather than being committed to writing.

In the late 11th and 12th centuries, this practice of spoken rather than written medical knowledge changed, paving the way for modern medicine through the revival of Classical Greek texts and the incorporation of scientific advancements by the Islamic world. As Greek philosophy and science were being resurrected from illegibility through translations (via Arabic into Latin) and a renewed interest in reconciling the ‘pagan’ ideas with Christianity, medicine— and science— in Western Europe began to make strides towards modernity.

The first medieval medical texts were based on Hippocrates and Galen. Other early medical texts that begin to appear in the 11th and 12th centuries are collections of herbal remedies and descriptions of the medical properties of plants. The Greek physician and botanist, Pedants Dioscorides (active from 40-90 BCE) produced one of the most well-known works on herbal properties which gained popularity and currency during this time. The work was distributed variously as Herbarium, De materia media, and, in the 19th century, published as Synonyma planetarium Barbara (Synonyms for Wild Plants). As this new interest in Greek and Arabic science grew in 11th century Italy, it spread north, to France and calques were developed to help bridge the gap between the Greek terminology and the Latin lingua franca. Thus, books of Latin synonyms of the Greek and Arabic words were composed in the 12th and 13th centuries as a way to make practical sense of the waves of new herbal information that flowed into European hands from medical books discovered by Westerners in the Holy Land during the Crusades. Dioscordie’s works were interpolated into a Herbarium attributed to Pseudo-Apulius, further confusing the trail textual transmission and the line of scientific discoveries. With the frenzy for better understanding the Greek and Arabic medical texts, such as those of the Ancient Greek medical writer, Serapion, and the Arabic physicians Rasis and Avicenna, anonymous scribes in the West composed the corresponding Synonyma Rasis, Synonyma Serapionis and Synonyma Avicennae, as well as many others not devoted to a single author or text. In an effort to bring order to the cacophony of such texts with a single unified replacement, Simon de Gênes compiled the Clavis sanationis in the late 13th century.

Bifolium from an herbal glossary in the Synonyma tradition, in Latin, manuscript on parchment [France, twelfth century]. Each leaf 185 by 146mm. Two conjoined leaves, each with single column of 25 lines in a small and angular early gothic bookhand, with a few biting curves, plant names underlined in black ink, apparently reused on accounts in sixteenth century with probable date of those accounts “1592” added to bas-de-page of one page upside down, liberated from those accounts by the nineteenth century and with inscription of that date at head (“Live de medicine fin XI ou comment du XII”), cockling and stained areas, a few tears to edges, but without affect to text, overall good and presentable condition.

A glance at the document reveals the types of medical complaints medieval physicians were armed to deal with: fevers, spondylitis, apostema (abscesses). We see the transliteration of Greek words such as Αποστεμα, which gives apostema, known in English as an abscess. Συνοχή gives sinoche; that is cohesion. A list of herbs and complaints, transliterated and translated in a formulaic “id est” shows the Greek words ‘diaquilon,’ (of juices), ‘libanotidos,’ (rosemary), ‘diacausis,’ (around the fire), ‘epiplocei,’ (replenishment of fluids, which is also a Greek word for a specific type of hernia), ‘radomes,’ (rose and honey), as well as many others.

We have not been able to identify the present text among published examples, and this may well be the only recorded witness to this text.

This bifolium stands as a bridge in the transition between medieval and modern medicine. While scholars have understood for a long time the importance of this 11th and 12th century period for the development of European science and medicine, the rarity of the manuscripts from this time period has proven a stumbling block in understanding how the knowledge spread and the nuance in its development. These leaves contain numerous entries of medicinal plants (usually Latin transliterations of Arabic or Greek plant names), with brief glosses on alternative names and uses. They are most probably all that survives from a codex with a now-unknown synonyma-text.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services