From the Sermons of Pope Gregory the Great, Who Brought Post-Roman Christianity to the British Isles, Written in 11th Century Italy

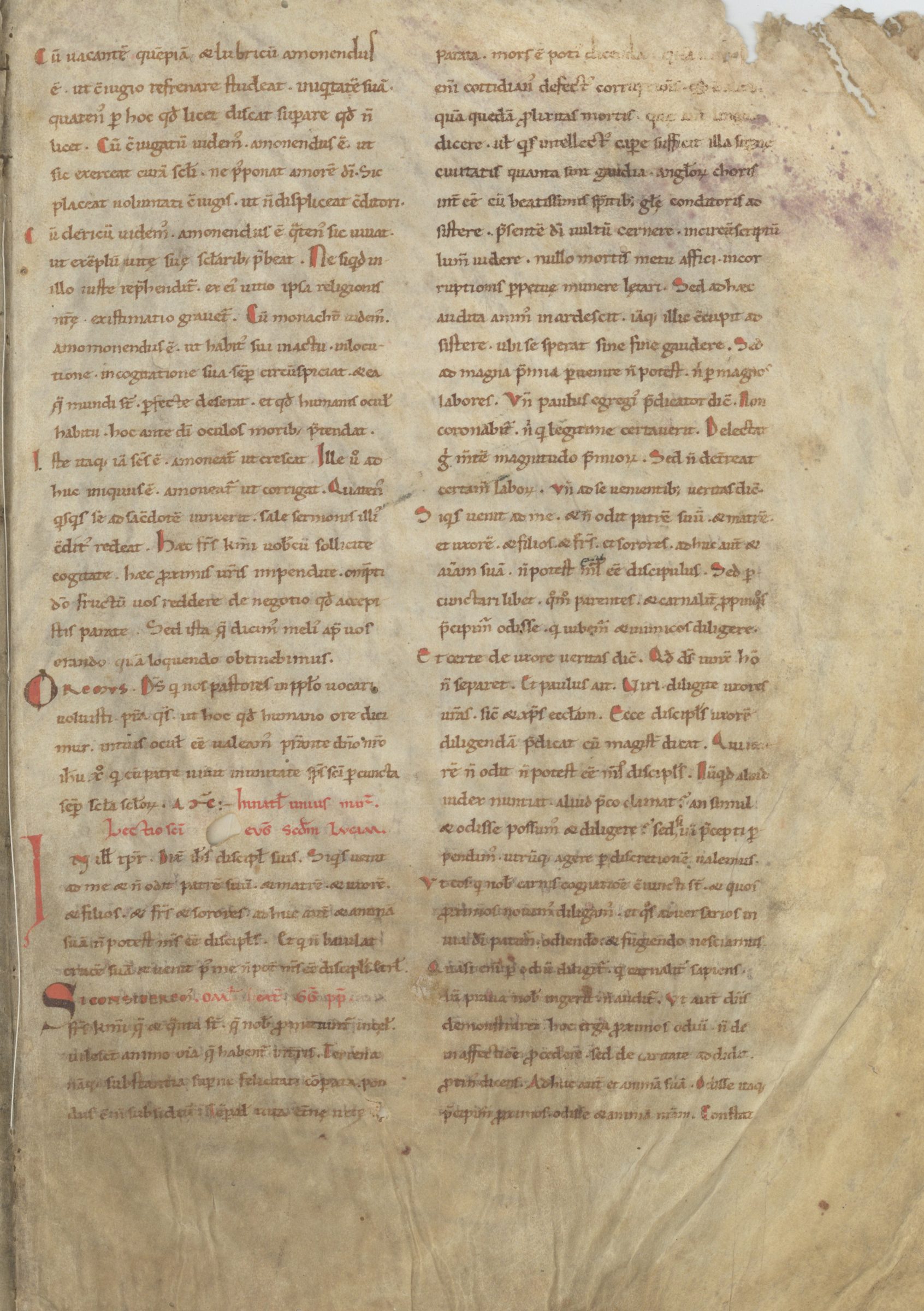

This set of manuscript leaves shows the world immediately following the turn of the first millennium and includes a rare note from the scribe to his rubricator

- Currency:

- USD

- GBP

- JPY

- EUR

- CNY

The important messages Gregory spoke nearly 500 years before the manuscript was made—that he spoke during the aftermath of a plague and collapse of an empire—were still relevant to the scribe who carefully copied out the homilies

“Earthly substance compared to heavenly happiness is a weight, not a support.”

Modernity’s view of...

The important messages Gregory spoke nearly 500 years before the manuscript was made—that he spoke during the aftermath of a plague and collapse of an empire—were still relevant to the scribe who carefully copied out the homilies

“Earthly substance compared to heavenly happiness is a weight, not a support.”

Modernity’s view of Pope Gregory the Great derives from his own words and from an imaging of the zeitgeist of the 6th century that the saint navigated. One early 20th century historian wrote of Pope Gregory that:

Growing up amid the relics of a greatness that had passed, daily reminded by the beautiful broken marbles of the vanity of things, he [Gregory] was accustomed to look on the world with sorrowful eyes. The thrill, the vigour, the joy of life were not for him.…He never attained a perfect sanity of view. From his birth he was sick—a victim of the malady of the Middle Ages. (Dudden)

Though this description may be consistent with the romanticized view of the 18th century antiquarian Edward Gibbon more than it accurately depicts Gregory (Leyser), the tumult and transition of the era must have impacted Gregory.

Born around 540 C.E., Gregory was immediately thrust into a world stricken with plague. This pestilence, which would be known as the Black Death in the later Middle Ages, was at this time called the Plague of Justinian (due to the Emperor’s recovery from it) and was the first occurrence of this strain of Yersinia pestis in Europe. In 590, Pope Pelagius II was not as fortunate as Emperor Justinian and succumbed to the disease— leaving the Holy See open for Gregory to assume as the natural successor to Pelagius (Leyser).

From 590 until his death in 604, Pope Gregory achieved his appellation of “the Great.” During his papacy, he began to shift the power centre back from Constantinople to Rome. He reformed and reshaped liturgy and arguably the most well known style of music from the Middle Ages, the Gregorian chant, described as such in the 9th century, took his name because of his impact on plainchant centuries earlier. His influence was felt both on the Italic peninsula and in the far flung reaches of Germany and Britain.

While a unified Italy would not be achieved for another nearly 13 centuries, the battle for a unified Christian theology across boundaries had already begun. With some groups still rejecting Christianity wholesale, other groups believed different dogmas of the religion. One particularly popular version was Arianism, which did not believe in the equality of the Holy Trinity, rather that Jesus, born of a human woman, could not be of the same status as God and the Holy Spirit. As the Germanic Lombards amassed their kingdom in the North of Italy, they staked out their Arian belief system. Gregory, however, befriended the Lombard Queen-by-marriage, the Bavarian Theoldelinda, who became a follower; she in turn influenced her husband, Autori, to adopt a Romanitas and convert to Nicean Christianity.

In 596, the Gregorian mission— the pope’s effort to convert the Anglo-Saxon peoples in Britain— was under way. Though after the Romans withdraw from Britain in 410, a good portion of the population remained Christian, the Anglo-Saxon peoples were still practicing pagans and the separation from Rome led to distinct differences between Continental and Insular Christianity. Gregory saw an opportunity to complete the conversion of the British peoples in the Kentish King Æthelberht’s marriage to the Frankish and Christian Bertha. Thus, he sent Augustine of Canterbury and Paulinus of York to the Islands, and the conversion was under way.

Shortly before his mission efforts to Britain, in 592-593 or 590-592 C.E., Pope Gregory delivered the Holimiae in Euangelia (Homily on the Evangelists). These sermons would have been preached by Gregory and written down by scribes, who were also able to read the sermons for him if need be (Markus 16). These homilies come to us through an extant collection of around 400 still extant manuscripts (Judic, p. 233 n. 2).

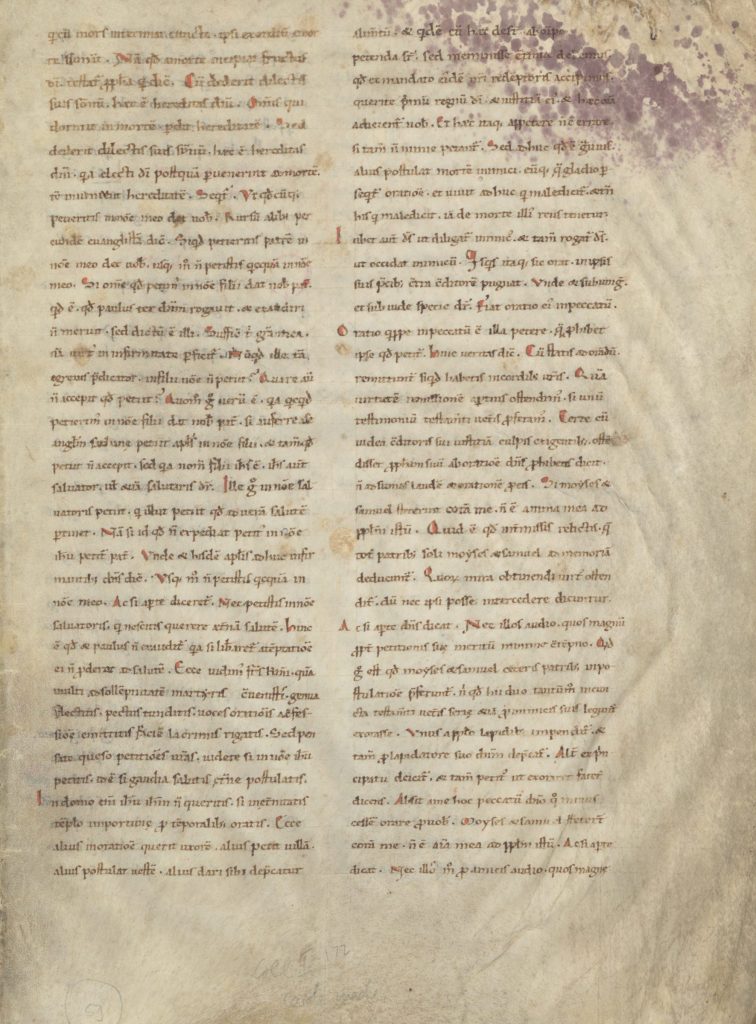

Medieval manuscript, Two vellum leaves from Books 1 and 2 of Gregory the Great’s Homiliae in Evangelia, Italy, 11th century, written in beautiful Romanesque script.

The text of these folios are primarily from Book 2, Homily 27 and 37, with one section from Book 1, Homily 4, explaining the works of Evangelists John, Matthew, and Luke. In these sermons he expounds how to be a good Christian and the heavenly promises awaiting. In one exemplary passage from these leaves, Gregory combines his passionate description of the kingdom of heaven, with his acute sense of the Apocalyptic return of Christ, as well as providing guidance for becoming more spiritually worthy. He writes:

“If we consider, dearest brothers, what and how great things are that are promised to us in the heavens, we despise in our hearts all that is held on earth. For earthly substance compared to heavenly happiness is a weight, not a support. The temporal life compared to the eternal life is rather to be said to be death than life. For what is the daily lack of corruption but a kind of prolongation of death? But what language is sufficient to say, or what understanding is sufficient to comprehend the joys of the heavenly city, to participate in the choir of angels, to assist with the most blessed spirits of the glory of the founder, to behold the present face of God, to see the uncircumscribed light, to be affected by no fear of death, to rejoice in the gift of perpetual incorruption? But when he heard these things, his heart was inflamed, and he now desired to attend there, where he hoped to rejoice without end. But great rewards cannot be attained except through great labors.” (fol. 2 r).

This set of manuscript leaves lets us glimpse into the world immediately following the turn of the first millennium. The human touch behind the production of the manuscript comes to the fore through the unusual remains of the note from the scribe to his rubricator to add the section heading in red. The important messages Gregory spoke nearly 500 years before the manuscript was made—that he spoke during the aftermath of a plague and collapse of an empire—were still relevant to the scribe who carefully copied out the homilies, paying attention to add delicate serifs on the feet of the descending strokes to make the physical manifestation of the words as impactful as their message.

More details:

Two vellum bifolium with sections from Books 1 and 2 of Gregory the Great’s Homiliae in Evangelia, Italy, 11th century, second half, in Latin, four leaves (two sets of two leaves conjoint), 364 x 265 (written space: 288 x 188) mm, with double columns of 38 lines in fine Romanesque script, Æ in ligature, prepositions joined to the words they govern. Both tall & uncial-type d; ampersand for et. Consistent use of common abbreviations. Brown ink for main text, headings in rubrication (red) with letters beginning sections tipped in red. Two and three-line initials in red.

These leaves demonstrate the production process of the manuscript. The leaves would have been folded in the centre, leaving two columns of text on each side and stacked into each other and sewn to create packets, called quires or gatherings, of leaves. Thus, the front and back (recto/verso) of the leaves are consecutive text, but the leaves themselves are non-consecutive, reflecting the stacking. Further remnants of the production process can be seen: the scribe’s directions to his rubricator— the person in charge of adding in the red letters— can be seen on the extreme edge of fol. 1 v (beginning with “audio merit orare…”). The letters written perpendicular to the main text correspond with the red letters on Column B reading in abbreviated letters “Lectio sancti evangelii secundum Matthaeum.” These types of directions are usually trimmed off during either the first stage of contemporary book production or in subsequent bindings, making the finding of one highly unusual.

Text Description:

All from Gregory the Great’s Homiliae in Evangelia (Homilies on the Evangelists)

Fol. 1:

Book 2, Homily 27, sections 5- 8 (“Addressed to the people in the Basilica of St. Pancratius the Martyr, on the Day of his birth”)

Fol. 1v:

Continued from recto, Book 2, Homily 27, sections 8- 9.

Book 1, Homily 4, section 1 (“Addressed to the people in the Basilica of Saint Stephan the Martyr, on the Apostles”)

Fol. 2:

Book 1, Homily 17, section 18 (“Addressed to the Bishops in the Lateran Baptistry”)

Book 2, Homily 37, sections 1-2 (“Addressed to the people in the Basilica of the Blessed Saint Sebastian the Martyr, on the day of his birth”)

Fol. 2v:

Continued from recto, Book 2, Homily 37, sections 2- 6.

Provenance:

Ex Bruce Ferrini, accompanied by a document prepared by Prof. Martin Colker of the University of Virginia.

Further reading:

Dudden, F. Homes, Gregory the Great: His Place in History and Thought, 2 vols. (London, 1905), i. 15.

Leyser, Conrad, Authority and Asceticism from Augustine to Gregory the Great, Oxford UP, 2000.

Markus, R.A., Gregory the Great, Cambridge UP, 2012.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services