Samuel F.B. Morse Fights Off Corruption in the Building of the First Telegraph Line

Blocking a corrupt payoff, he reports to the U.S. Treasury that the Senate is sympathetic to his stance.

“I called as you suggested immediately upon [U.S. Senator Ephraim] Foster and my explanation was perfectly satisfactory to him, and he expressed himself gratified that the matter had assumed the shape it has.“

Samuel F.B. Morse established his reputation as a portrait painter, and his travels took him to Europe. The idea...

“I called as you suggested immediately upon [U.S. Senator Ephraim] Foster and my explanation was perfectly satisfactory to him, and he expressed himself gratified that the matter had assumed the shape it has.“

Samuel F.B. Morse established his reputation as a portrait painter, and his travels took him to Europe. The idea of using electricity to communicate over distance is said to have occurred to him during a conversation aboard ship when he was returning from Europe in 1832. Michael Faraday's recently invented electromagnet was much discussed by the ship's passengers, and when Morse came to understand how it worked, he speculated that it might be possible to send a coded message over a wire. In 1837 he applied for a patent, and by December of that year Morse had enough confidence in his new system to apply for a federal government appropriation to build it. During the next year he conducted demonstrations of his telegraph both in New York and Washington, where he sent telegraph messages between the Senate and House wings of the Capitol. However, when the economic disaster known as the Panic of 1837 took hold of the nation and caused a long depression, Morse was forced to wait for better times.

By 1843, the country was recovering economically, and Morse asked Congress for the $30,000 that would allow him to build a telegraph line from Washington to Baltimore, forty miles away. The House of Representatives passed the bill containing the Morse appropriation, and the Senate approved it in the final hours of that Congress's last session. With President Tyler's signature, Morse received the cash he needed and began to carry out plans for a telegraph line. Morse also was aided by some private backers, including Congressman F.O.J. Smith.

Morse now considered whether to run the telegraph cable overhead on poles or underground. The underground method required trenching, insulated telegraph wire, and piping through which to run the wires. By the time the project was authorized, he elected the underground method for reasons of cost. But construction encountered numerous obstacles and delays. It was Morse's idea to protect his fragile copper wire by running it through protective lead pipe, half an inch in diameter. After bids were taken, Smith contracted with James E. Serrell to deliver 40 miles worth. But by Fall of 1843, Serrell encountered problems with its manufacture and could not produce pipe quickly enough. In fact, he could not produce more than a quarter of what Morse required. The exasperated Morse revoked the contract and hired Benjamin Tatham & Co. when that firm agreed to deliver the necessary amount of pipe by November. This was acceptable to Morse, who planned to demonstrate the Baltimore-Washington telegraph line when Congress convened in December. However, the delivery date was far too optimistic.

Meanwhile, to get things moving, Morse started to put down the existing ten miles of pipe. To excavate the trench in which to lay the pipe, Smith hired his brother-in-law Levi S. Bartlett. Morse objected that Bartlett’s price was too high and might seem extravagant to Congress, but with the press of time he allowed the trenching to get underway. When it did, it was hindered by rains; then it was found that the insulation on the wires (which Smith had secured) was failing, and the pipe being laid proved defective. With problems on all fronts, the entire telegraph project was jeopardized.

In December 1843, with nothing tangible to show for his work, Morse now decided to abandon the underground wire plan and pull the wire from the pipes; instead he turned to stringing his wire on poles, a plan that would ultimately prove successful. Bartlett had been contracted by Morse to dig a trench that was no longer needed, rendering its contract with Morse void. Bartlett cried foul and insisted on being paid the full price of the contract regardless of the fact that much of the trench would never be dug, and his brother-in-law Congressman Smith, who likely had a financial arrangement whereby both benefited, supported him. Smith drafted a letter to the Secretary of the Treasury Walter Forward for Morse to sign asking that Bartlett’s claim be honored. But Morse was outraged by what he thought was unethical conduct and refused to sign, and decided to stand in the way and block more payments to Bartlett. Smith involved Forward anyway, and the latter launched an investigation. In the end Morse and Smith bickered publicly, with Smith accusing Morse of being an incompetent superintendent who was mismanaging the telegraph project and costing his good-faith contractors money and Morse making his belief clear that there was corruption involved in the Smith/Bartlett claim. Morse stated that Smith was hounding him “because I refused to accede to terms…which I could not do without dishonor and violation of trust.”

On January 17, 1844, Bartlett appealed to the U.S. Senate, and his claim for compensation was referred to the Committee of Claims. Meanwhile, the U.S. Treasury Department’s investigation was proceeding. Gilbert Rodman was the Chief Clerk of the Treasury, and primary assistant to the Treasury Secretary. Rodman occasionally acted as Secretary of the Treasury during the absences of the primary office holders or when there were interregnums. On March 8, 1844, after considering the Bartlett matter and the information he had gathered from Morse, Rodman wrote a ten page report entitled “Answers to the Secretary’s inquiries in…the Controversy about the Electric magnetic Telegraph”. The report, all in Rodman’s hand and signed the day that John Spencer succeeded Forward as Treasury Secretary (having awaited the new Secretary’s approval), contains a fascinating, detailed and apparently unpublished account of the entire matter, including a timeline, and the actions and agreements of the parties. The March 8 report generally accepted Morse's assertions that Bartlett had been paid for the work performed and had no right to any more money from the government contract, concluding by saying: “From the data we have it is impractical to make any estimate of damage if any sustained by Bartlett, and this it strikes me arises from no laches [unnecessary delay] on the part of Mr. Morse or the Dept. Smith was called upon to submit his claim with proper proof – he has not done so. I do not think he is entitled to one cent beyond what he has already received…” Rodman found no fault with Morse’s management of the project.

Rodman’s report went to the Senate Committee on Claims, which was chaired by Sen. Ephraim H. Foster of Tennessee. The committee considered it, and as a follow up Morse went to speak with Foster in person. Morse then reported the upshot to Rodman.

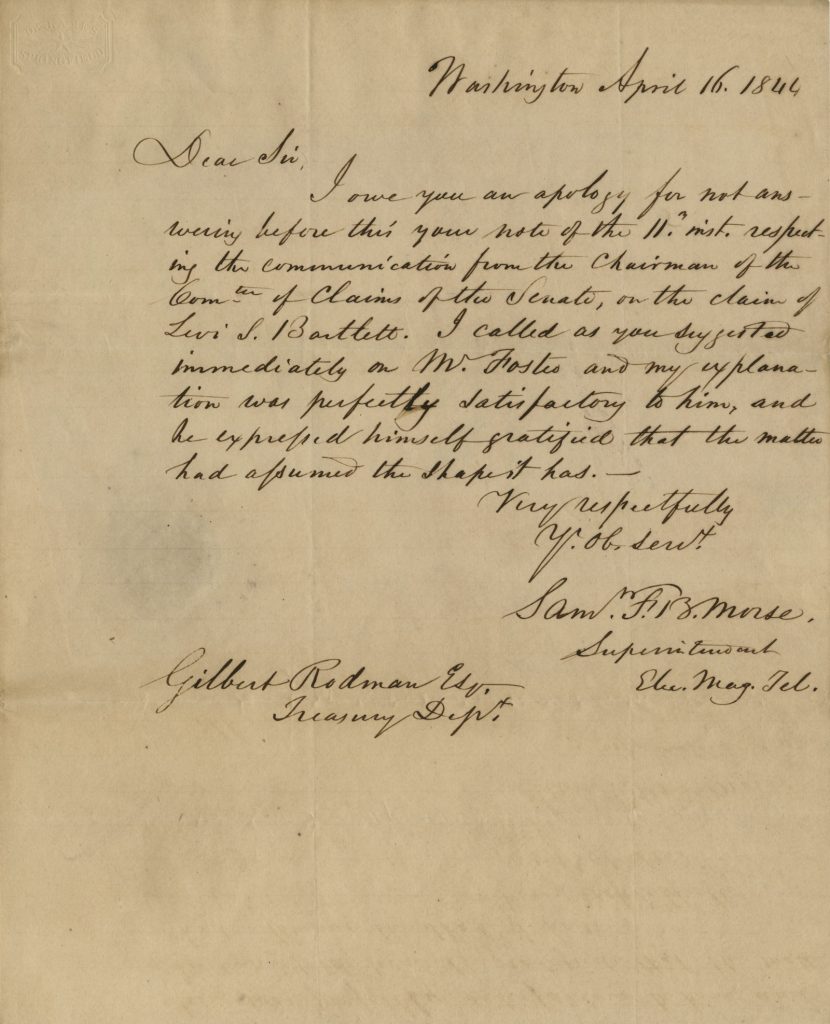

Autograph letter signed, Washington, April 16, 1844, to Rodman, telling him that he had met with Foster, who proved unsympathetic to the Smith/Bartlett claim. “I owe you an apology for not answering before this your note of the 11th inst. respecting the communication from the Chairman of the Committee of Claims of the Senate, on the claim of Levi S. Bartlett. I called as you suggested immediately upon Mr. Foster and my explanation was perfectly satisfactory to him, and he expressed himself gratified that the matter had assumed the shape it has.“

The original Rodman report comes with this letter, so there are 11 pages in this group.

Using above-ground poles to run the wires, the first telegraph line was completed in the Spring. On May 11, 1844, Morse sent the first inter-city message. Then, on May 24, standing in the chamber of the Supreme Court, Morse gave the first public demonstration, sending the famous 19-letter message, "What hath God wrought”, to his assistant Albert Vail in Baltimore, who transmitted the message back. This remarkable event marked the beginning of a new era of communication, in which information could travel faster than any human by any means of conveyance.

June 15, 1844 the Senate Committee of Claims dismissed the Smith/Bartlett petition.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services