NOT A GROUP The Archive of Judge Jacob Trieber, the First Jew to Be Appointed to the Federal Bench

Trailblazer of Civil Rights and Antitrust Law.

Jacob Trieber was the first Jew to serve as a federal judge in the United States. Serving from 1900 to 1927 as judge for the U.S. Circuit Court, Eastern District of Arkansas, he issued nationally important rulings on controversies that included antitrust cases, railroad litigation, prohibition cases, and mail fraud; some of...

Jacob Trieber was the first Jew to serve as a federal judge in the United States. Serving from 1900 to 1927 as judge for the U.S. Circuit Court, Eastern District of Arkansas, he issued nationally important rulings on controversies that included antitrust cases, railroad litigation, prohibition cases, and mail fraud; some of his rulings, such as those regarding civil rights and wildlife conservation, have implications today. His broad interpretation of the constitutional guarantees of the Thirteenth Amendment, originally overturned by the post-Reconstruction U.S. Supreme Court, was validated sixty-five years later in a landmark 1968 equal opportunity case.

Jacob Trieber was born in 1853 in a part of Prussia that is now Poland and was a descendant of a rabbinical family. He immigrated to America when he was thirteen years of age. He became an attorney and was the youngest delegate to the Republican National Convention in 1880. Trieber was one of the 306 stalwarts for Grant, sticking with him though the nod went instead to James A. Garfield. He attended the 1896 Republican Convention as a delegate pledged to William McKinley and saw his candidate nominated and elected. Within a year of McKinley’s inauguration, Trieber was named U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Arkansas.

In July 1900, when a vacancy occurred in the federal judgeship for that district, Arkansas Republican state chair H.L. Remmel was invited to the White House to an interview with President McKinley and his political advisor, Mark Hanna. Remmel urged the President to appoint Trieber federal judge but specifically took up Trieber’s Jewish faith with the President to make sure he was aware. McKinley was not daunted and made the historic appointment of Trieber on July 26. This was a courageous move for McKinley, as no Jew had ever before been appointed a judge on any Federal bench. The U.S. Senate confirmed the appointment in January 1901.

Trieber’s pioneering civil rights decisions

Trieber used his judicial position to attack racism and injustice directly. His first important cases involved a group called the whitecappers, which flourished in place of the outlawed Ku Klux Klan. They terrorized blacks and their white sympathizers, at times attempting to prevent blacks from obtaining employment. In 1903, in U.S. v. Hodges, fifteen armed whitecappers who forced a sawmill to fire its black workers were charged with violating the 19th century civil rights acts. At about the same time, another group of whitecappers was charged with terrorism in U.S. v. Morris. In his instructions to the grand jurors, Trieber required them to consider illegal the intimidation of a person pursuing employment. In his celebrated opinion in Morris, he held that “the rights to lease lands and to accept employment for hire are fundamental rights, inherent in every free citizen,” and thus guaranteed by the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The ringleaders of the whitecappers were convicted, quite an accomplishment at that time. Some of the convicted defendants appealed Trieber’s ruling to the U.S. Supreme Court which overruled Trieber on the grounds that the ability to earn a living was not a fundamental right of citizens protected by the Thirteenth Amendment. The Supreme Court’s decision in Hodges led to much discrimination and tragedy. Judge Gerald Heaney of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit wrote in 1985, “For almost fifty years…the Hodges case…became the rod and staff of those who denied that the federal government had the authority to intervene in race relations.”

It was not until the Civil Rights Act of 1964 that comprehensive protection against racial discrimination in employment was established. In 1968, in Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., the Supreme Court overturned its 1906 ruling in Hodges. The Court’s opinion cited approvingly Trieber’s farsighted ruling in the Morris case, and noted that Trieber had been the sole Federal judge ever to take on the issue of right to employment. “The only federal court…that has ever squarely confronted that question held that a wholly private conspiracy among white citizens to prevent a Negro from leasing a farm violated §_982. United States v. Morris, 125 F. 322.” Thus, writes Judge Heaney, “Judge Trieber’s interpretation of the Thirteenth Amendment and the Civil Rights Act of 1866 was at last vindicated.”

Trieber played a crucial role in the first case concerning the justice given to African-Americans in the South that came before the Supreme Court in the 20th century. In the 1919 Elaine racial clash, a white railroad employee accompanying a deputy sheriff was shot and killed after he and a number of white landowners fired into a church where a black tenant farmers union was meeting. In the week after the shooting roving bands of whites and government troops killed upward of 200 blacks. Then some 100 blacks were charged with crimes, some of which included murder. The trials were mob-dominated, as crowds of armed whites milled around the courthouse, and all the defendants were convicted. Appeals were taken but got nowhere. Finally, a habeas corpus petition came before Trieber. Because of a previous Supreme Court ruling, he felt that he could not grant it outright. However, he held that the defendants had probable cause for their petition, which enabled them to appeal to the Supreme Court. In Moore v. Dempsey, the Court found for the black defendants and established precedent for wider use of federal writs of habeas corpus to oversee state court convictions that occurred in violation of federal Constitutional rights, as well as marking the beginning of stricter scrutiny by the Supreme Court of state criminal trials.

Trieber’s defining Constitutional law decisions

In a series of Constitutional law decisions that continue to have implications, Trieber defined the extent of Federal and state authority. Congress passed the Migratory Bird Act in 1913 to protect migratory birds by limiting the hunting of these birds. A person indicted for violating that law moved to dismiss the case on the grounds that the act contravened the 10th Amendment by invading the jurisdiction of the states. In deciding that this act was unconstitutional, Trieber noted that the common law provided that the states essentially owned the birds within their borders and state legislation was the sole source by which control of hunting could be accomplished. In response, the Federal government concluded a Migratory Bird Treaty with Canada containing many of the same regulations, and the treaty was ratified by the U.S. Senate. Congress then adopted enabling legislation. A similar case again came before Judge Trieber, who ruled in upholding the act, and thus its application within the jurisdiction of Arkansas, that the Constitution grants to the U.S. government sole treaty-making authority. He wrote, “Even in matters of a purely local nature, Congress, if the Constitution grants it plenary powers over the subject, may exercise what is akin to the police power, a power ordinarily reserved to the states…” The legal strategy of using international treaties in order for Federal policy to trump state regulation has since been used to support legislation on foreign trade, pollution control, endangered-species preservation, and wetlands conservation, among others.

Trieber’s pioneering antitrust law decisions

Trieber played a key role in laying the foundation stone to antitrust law. The Sherman Act of 1890 ostensively prohibited restraints of trade, but Supreme Court rulings that forced purchasing arrangements (called tying) were not covered and dramatically limited their application. The Clayton Act was passed in 1914 to plug loopholes in that law and expand its scope. In 1916, with the case of U.S. v United Shoe Machinery Co. on the docket and likely to determine whether the Clayton Act was constitutional, Chief Justice Edward White asked Trieber to take the complex matter and he agreed. The case lasted for four years by the end of which Trieber’s rulings had upheld the constitutionality of the Clayton Act and used the commerce clause of the U.S. Constitution to do so. Trieber’s decision was upheld by the Supreme Court which settled antitrust law and foreshadowed the broader interpretation of the commerce clause that was to come. In April 1927, Chief Justice William H. Taft appointed him to preside over a pending restraint of trade case involving the Journeymen Stone Cutters in New York. Trieber accepted the assignment and started the trial. However, on September 17, 1927, before it could be completed, he died at age 74.

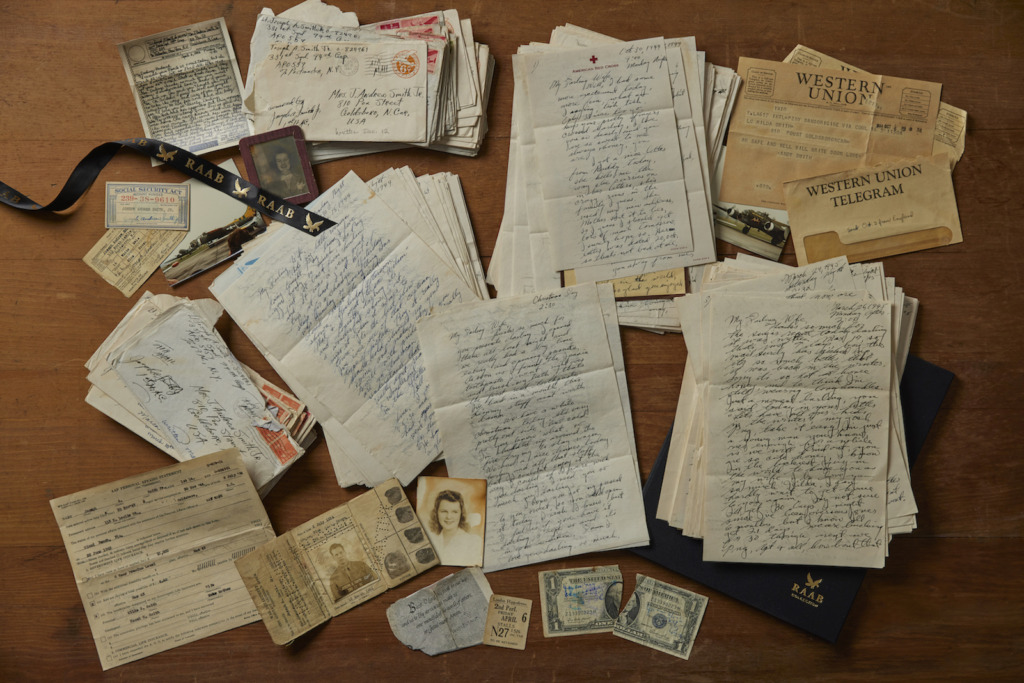

The Archive

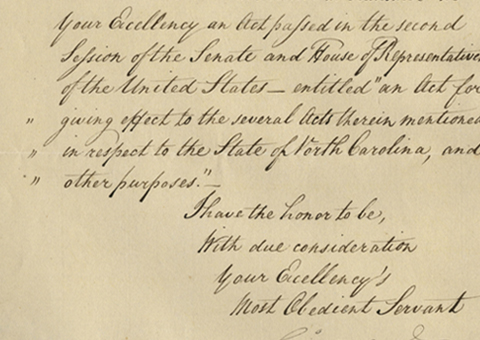

McKinley’s appointment of the first Jewish federal judge:

Document Signed, Washington, January 9, 1901. “Reposing special trust and confidence in the wisdom, uprightness and learning of Jacob Trieber of Arkansas, I have nominated, and by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, do appoint him United States District Judge for the Eastern District of Arkansas, and do authorize and empower him to execute and fulfill the duties of that office according to the Constitution and Laws of the United States.”

Trieber’s oath of office:

On the verso of the McKinley appointment appears Trieber’s signed oath, dated January 19, 1901. “I, Jacob Trieber, do solemnly swear that I will support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign or domestic… and that I will well and faithfully discharge the duties of the office of United States District Judge for the Eastern District of Arkansas on which I am about to enter. So help me God.”

Trieber’s hand-written case journal, listing his major cases and the principles and citations he wanted to keep at hand:

This journal, well used, has his name engraved in gold on the cover. The first section of 92 pages contains hundreds of legal topics and points of law, and includes specific case citations relating to each of them. In antitrust and restraint of trade, he lists “Illegal combinations. Even if act of one not illegal, if 2 or more conspire it may be…Grenada Lumber Co. v State of Mississippi, 217 U.S. 433.” In Constitutional law, he lists “Searches and seizures. When warrant not necessary…Green v U.S., 289 F. 236.” Concerning securities regulation, he notes “Blue Sky laws…What state may regulate…What is commerce, what not…What right for review by courts granted…” and gives cases. There are a number of listings under “Interstate commerce,” including one “What [constitutes] interstate shipments… B&O Railroad v Settle, 260 U.S. 166.” This is a small fraction of the material.

Following these entries is an 8 page list of the hundreds of cases in which he had written opinions, each one complete with citation. A number have his notation as to whether his opinions were affirmed or reversed on appeal (there were very few reversals). He notes the famous Hodges and Morris cases as “Whitecapping cases” under “U.S. v Morris,” and indicates that that case was appealed and reversed. There is also a 4 page list of his cases that were taken to the Court of Appeals and a 5 page index.

Blacks credit Trieber with helping to suppress the racist whitecappers:

A resolution from the “colored Republicans of Arkansas,” May 1, 1905, urging President Roosevelt to appoint Trieber to a vacancy on the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals “… We recommend him for his soundness and patriotism in enforcing the amendments to the Constitution of the United States designed to protect all American citizens, as illustrated by his able and comprehensive decisions, rulings and charges respecting whitecapping and peonage by means of which those crying evils are already well-nigh suppressed in the state of Arkansas.” This document is signed by John E. Bush, the foremost black Republican in the state. Born a slave, he became a newspaper publisher. In 1898 he was appointed U.S. Land Office Receiver by President McKinley. He was reappointed to that post by Theodore Roosevelt and again by President Taft.

Trieber’s Rules of Practice plus his jury instructions:

His copy of the Rules of Practice for the United States District Court, Eastern District of Arkansas, for the year 1926, and a twelve page draft of instructions to the jury in a defamation case showing Trieber’s legal writing style.

Trieber’s recognition and letters from Chief Justice (and former President) William Howard Taft:

There are 14 letters of Taft, all on Supreme Court letterhead, 13 of which are to Trieber and one which relates to him. Some of them are significant. The earliest letter dates from September 27, 1921, just two months into Taft’s Chief Justiceship, and is addressed to H.L. Remmel. Taft writes “I…note what you say about Judge Trieber. Everything I hear about Judge Trieber is good…” On February 7, 1923, Taft taps Trieber for a special assignment, asking him “Do you think you could spare any time for judicial work in New York City this summer?_If you could give us a month, you would do a great service…” Trieber also requests the Chief Justice’s opinion on an ethical question. His son had become an attorney, and Trieber was concerned about the propriety of the son appearing in court before the father. He thought that perhaps he ought to resign to further his son’s career. Taft answered, “I suggest not that you resign or that your son move elsewhere, but that he be a little chary of appearing before you. Let his partners attend to the United States Court business. This may be a little inconvenient, but it will…save you from criticism…” On November 20, 1925, Taft again requests that Trieber come to New York where additional judges are needed as “they are in a great fight there.” He continues, “…you can do about twice the work of an ordinary judge.” Following the 12 typed letters are two hand-written ones. On June 15, 1925, Taft does Trieber the honor of saying that another judge has “told me you had written an article of the effect of the Act of February 13, 1925 on the jurisdiction of the Circuit Court of Appeals. May I ask you to do me the favor of sending me a copy. I have to write an article on the subject for the Yale Law Journal and I would be willing to plagiarize from so reliable and exact authority.”

Taft appoints Trieber Senior Circuit Judge:

Trieber finally relented and agreed to assist Taft by accepting the assignment of trying an antitrust case in New York. This document, dated June 4, 1927 and signed by Taft, designates “Hon. Jacob Trieber to perform the duties of District Judge and hold a district court during the period beginning July 15th, 1927 and ending September 17th, 1927, and for such further time as may be required…”

Trieber’s correspondence with Theodore Roosevelt:

In 1905, Trieber wrote President Roosevelt about the situation of blacks in the South. The President’s secretary would later contact Trieber to say that Roosevelt would like to see him when he is in Washington. There are two letters on White House letterhead signed by TR, the latter one dated three days before he left office saying, “You have written me just the kind of letter it pleases and touches me to receive, especially coming from a man like you. Believe me, I appreciate it.” There is another letter from Roosevelt in 1911. In 1912, in the run-up to Roosevelt’s Bull Moose campaign, Trieber sent TR a 4 page letter, a retained copy of which, signed by Trieber, is in the collection. It suggested that the Constitution would be more responsive to the people, and less hidebound by antiquated court rulings, if it were easier to amend. Roosevelt responded on February 29. “I am immensely obliged to you for that letter. It is most valuable.”

Trieber’s naturalization papers:

This is a three page document dated May 11, 1887, relating the proceeding in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Arkansas, the very court to which Trieber would be named fourteen years later. After reciting his renunciation of allegiance to the Emperor of Germany, it “ordered that the said Jacob Trieber be and is hereby admitted and declared to be a citizen of the United States of America.” It is signed by the clerk of court and sealed with the court seal. The naturalization papers of his father are also present.

Trieber’s medal for supporting Grant at the 1880 Republican Convention, struck using metal from the last cannon to be fired at Appomattox:

Trieber was one of U.S. Grant’s “Old Guard” at the 1880 Convention. The loyal 306 men received a gift from the grateful Grant campaign – a 2 3/4 inch diameter bronze medal featuring a bust profile of Grant surrounded by laurels and a series of numbers to 306, “Commemorative of the 36 Ballots of The Old Guard for Ulysses S. Grant for President.” This is Trieber’s “Old Guard” medal.

One of Trieber’s most treasured mementos:

A glass brick that five distinguished friends took turns “stealing” from each other. It was originally owned by merchant I.H. Richards in 1871, at which time Charles Babcock heisted it. Justice Stephenson, Trieber’s mentor, had it from 1873-75 and 1904-5. Samuel Delatour, clerk of the U.S. District Court, held it from 1875-78. Trieber held it from 1903-4 and from 1905 on. A sheet pasted on the back of the brick relates the tale and documents the possession. On it, Trieber has written “Don’t let Stephenson lay violent hands on this.”

Hundreds of letters from Arkansas and Judicial Notables:

Letters supporting him for and congratulating him on his appointment, and various other topics, including a letter from his mentor, Marshall L. Stephenson, colonel of the 2nd Arkansas Cavalry (Union) in the Civil War, congratulating him on his appointment and looking to the future, and a letter from Arkansas Republican state chair H.L. Remmel, who was invited to the White House in an interview with President McKinley and wrote to Trieber to describe his first telling McKinley that Trieber was Jewish.

Over a hundred press clippings detailing Trieber’s entire career, plus other artifacts and copies of many articles by him and about him:

These were kept over the course of the past century by the Trieber family. Included is a photo album and press book kept by Mrs. Trieber.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services