Benjamin Franklin in Paris Struggles to Keep the United States From Financial Failure

ALS from France, 1777.

On September 26, 1776, the Continental Congress elected three commissioners to the Court of France, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson and Silas Deane, their mission being to raise money for the American Revolution, procure arms and supplies, and to negotiate a treaty of commerce and alliance with the French. Because of his wife’s...

On September 26, 1776, the Continental Congress elected three commissioners to the Court of France, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson and Silas Deane, their mission being to raise money for the American Revolution, procure arms and supplies, and to negotiate a treaty of commerce and alliance with the French. Because of his wife’s illness, Jefferson could not serve, so fellow-Virginian Arthur Lee, the brother of Richard Henry Lee, was appointed in his stead. Lee had been acting as a colonial representative in London when the Revolution broke out and was already in Europe speaking informally to the French, so it was a natural choice. When the selection was announced, Franklin turned to another delegate and said: "I am old and good for nothing, but, as the storekeepers say of their remnants of cloth, ‘I am but a fag end, you may have me for what you please.’" So far as the welfare of the United States was concerned, the most valuable part of Franklin’s life was actually still before him.

In March 1776, even before his appointment, Silas Deane arrived in Paris posing as a merchant and was well received by the French. He managed to enlist the support of the Comte de Vergennes, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, and by that summer, the French and Spanish governments both began giving clandestine aid to the Americans, providing munitions through a Portuguese company and pledging a funds to be employed in the purchase and charter of ships for the transportation of military stores. Deane was the sole American agent in France until Arthur Lee came over from England in December, closely followed by Franklin, who arrived in Paris on December 21, 1776. Franklin was the “celebrated Dr. Franklin” from the beginning. As symbolizing the liberty for which all France was yearning, he was greeted with great popular enthusiasm. Thinkers like Diderot regarded him as the embodiment of practical wisdom. The people gathered in crowds to see and acclaim him and shopkeepers rushed to their doors to catch a glimpse of him as he passed along the sidewalk. The nobility lionized him and placed laurel wreaths on his head on ceremonial occasions, while in evening salons be-jeweled ladies of the court vied with one another in paying him homage. His picture appeared everywhere. For his part, Franklin understood how the French saw him, and exploited that image on behalf of the American cause. Perhaps no person in history has come to symbolize America as Franklin did in Paris.

In France, Franklin wore many hats. He acted as diplomat charged with both convincing France to ally itself with America and fund the Revolution; purchasing agent to acquire ships and war supplies to be sent home; head recruiter seeking experienced or promising officers like Lafayette for the Continental Army; loan negotiator to obtain monies the virtually bankrupt Congress needed to carry on the war effort; admiralty judge for dealing with naval matters that arose in the waters around Europe; intelligence strategist handling information in the chess game between the American, French, British and Spanish governments; funds disburser for the vast American acquisitions effort; and was generally the main representative of the new United States in Europe. Yet to implement this entire program, Franklin was given neither funds nor a viable method of raising any. The ship which brought him to France also brought indigo to the value of £3000, which was all the funds that Congress provided. It was the intention of Congress to regularly purchase cargoes of American products, such as tobacco, rice and indigo, and consign these to the Commissioners, who besides paying their personal bills, would use the rest of the proceeds to fund their embassy. This scheme was, however, never worked and Franklin’s mission was not funded. He would need to find the money himself both for the war and his own operations.

Just two weeks after Franklin’s arrival, the American Commissioners formally requested French aid. King Louis XVI approved a response to them and on January 13, 1777 they received a verbal promise of two million livres. In March 1777, Franklin established himself at Passy, a charming village outside Paris where he remained throughout his French mission. In early June, he and Deane received the first proceeds from the French, an advance of one million livres, which they immediately deposited with the banker of the United States in Paris, M. Grand. The Americans were obligated to deliver tobacco later that year in repayment.

Meanwhile, in February 1777 Lee had left for Spain, where he was not officially received but was given an indefinite promise of future aid. Between May and July he was in Berlin fruitlessly seeking permission to use Prussian ports for American privateers. His diplomatic forays having little in the way of results, Lee then returned to Paris. John Adams was similarly unsuccessful in obtaining immediate funds in Holland.

Congress, informed that some money would be forthcoming from France, and having no cash on hand in Philadelphia to pay for its bills for the war, began sending them to Franklin. Moreover, Congress began ordering ships, munitions and other badly needed supplies, generating another procession of drafts for Franklin to pay. Efforts to get Spain, Prussia and Holland to provide financial help being largely unavailing, Congress also instructed Franklin to pay its already-existing foreign bills and indebtedness. In addition to all this, Franklin had to raise his own funds for all of his mission’s operations, as well as the other American embassies in Europe. Since only Franklin in Paris could tap the rock and make the needed funds flow, upon him fell the heavy task of keeping his country from financial failure even as Washington had to save it from military failure.

The French, though sympathetic, did not simply open their coffers. The amount of funds they provided was not initially substantial and Franklin was soon put to devising ways to obtain more. Moreover, France hoped to keep the American war at a low level while buying time to await events and prepare for a potential wider conflict with Great Britain. In the spring of 1777 Franklin was informed that the hoped-for navy would not be ready to dispatch to America until March 1778. The pressure on the American Commissioners increased in late summer, when the aggressive American use of privateers attacking British shipping from the haven of French ports threatened to bring on an immediate, and from a French point of view, premature war. This led the French to conclude that they could no longer prop up the American cause through secret aid, but would need a formal offensive and defensive alliance. Since the military news coming from America in the summer of 1777 was not good, France looked to Spain and they both hesitated to make such an alliance. The situation became worse when news arrived in September of American reverses in the field near Philadelphia, and Franklin struggled to present a positive impression and prevent America’s friends in France from getting too cautious or discouraged. By September, although the bills kept coming, the initial sums France had advanced to the United States bank account were exhausted. Franklin determined that he must approach the French with a request for more. This he did on September 25, pleading with the French for the vast sum of 14 million livres.

To finance, obtain, collect, and ship goods to America in a time of war, with the enemy controlling the seas and having great influence on land, was a task that could not be left solely to the diplomats. Experienced, successful merchants with shipping connections were needed to manage the effort. The task also necessitated the establishment of agencies in the French port of Nantes and in Paris. In May 1776, John Ross, a noted Philadelphia merchant well acquainted with Franklin, was employed by Congress’s Committee of Commerce to purchase clothes, arms, and powder for the Continental Army. Arriving in Nantes in 1777, Ross quickly found that Congress had not allocated nearly enough money for the task it had commissioned. In the early summer of 1777, after arranging for materiel to be shipped back to America and needing funds for the transaction to proceed, he approached Franklin, Deane and Lee and laid the Commerce Committee’s order before them. The Commissioners advanced Ross, on a temporary basis, some of the money they had received from the French in June. By September, pressed for funds to the point that they would soon be forced to seek more from the French, the Commissioners wrote Ross asking for repayment.

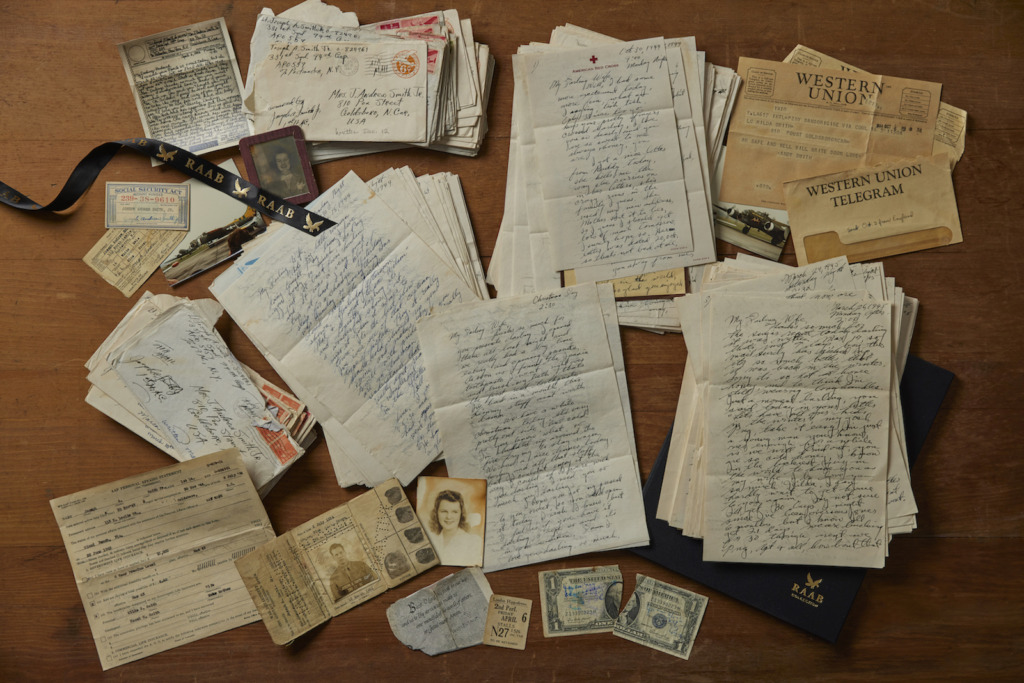

Autograph Letter Signed "B. Franklin" and additionally signed by Silas Deane and Arthur Lee, Passy near Paris, September 13, 1777, to "John Ross, Esq, Merchant at Nantes" urgently requesting payment of funds due them so as to use these toward repayment of the outstanding loan from France to the United States.

"…You gave us to expect at the Time we assisted You with Mr. Grand’s Draughts, for Four Hundred & Fifty Thousand Livres, that you would be able to repay it, or a considerable part of it soon; We must inform You that we are at this Time in very great want of it and pray You would make us as Considerable Remittance as may be in your power, if you are not able to discharge the whole Sum, which would indeed be more agreeable to Us and of great Service to Our Country…"

With integral address leaf in Franklin’s hand, postmarked "PAR" with handstruck "D 23" in red and "SP 16" in black, taxed "8" (décimes) in manuscript.

During his stay in France, Ross is known to have advanced or pledged his own credit for £20,000, so quite likely he dug into his own pocket and repayed Franklin with his own funds. In 1780, Franklin intervened with Congress on Ross’s behalf, trying to get him repaid. He never was.

News of the British defeat at Saratoga in October arrived in France on December 4, 1777, and spurred negotiations to conclude a French alliance. On February 6, 1778, Franklin, Deane, and Lee signed a Treaty of Amity and Commerce with France, as well as a Treaty of Alliance. This alliance would eventually lead to victory in the Revolutionary War.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services