Sold – Extremely Rare Investment Document From the Beginning of Andrew Carnegie’s Career

While still working for the Pennsylvania Railroad, he invests in an iron-making firm, and brings the railroad's president and vice president into the deal!.

Until after the Civil War there was no American steel industry, and in fact the entire steel-making process had barely been invented. In its place at the war's start was a small-time iron industry, in which a typical iron furnace cost about $50,000, employed some 70 men, and produced just 1,000 tons...

Until after the Civil War there was no American steel industry, and in fact the entire steel-making process had barely been invented. In its place at the war's start was a small-time iron industry, in which a typical iron furnace cost about $50,000, employed some 70 men, and produced just 1,000 tons of iron a year. Producing rails for railroads was their primary business. With the Civil War came the first large orders and continuous business, and every plant ran night and day. Of the $3 billion that the war cost the U.S. government, a goodly share went to the iron men.

Andrew Carnegie went to work for the Pennsylvania Railroad in 1853, at age 18, as a telegraph operator. He so impressed his boss, Thomas A. Scott, superintendent of the western division, that Scott named him his private secretary. In 1860, Scott became the first Vice President of the Pennsylvania Railroad, and a few years after Carnegie (at age 28) succeeded Scott as superintendent. As the chief aide to one of the most influential railroad magnates in Pittsburgh, and then a superintendent himself, Carnegie was in a position where all manner of special opportunities dropped into his hands. The first plum came in the shape of a chance to buy ten shares in the Adams Express Company, at $60 a share. His mother raised $500 by mortgaging their home, while Scott lent him the remaining $100; and he became a capitalist. Every month Carnegie received a dividend of $6, which opened his eyes to the magic of share-holding. From then until 1865, Carnegie was an active investor in the projects of others, seeking out ventures, generally preferring those with some relation to railroading, and sharing the investments with senior colleagues at the railroad. Carnegie still, however, remained in the employ of the Pennsylvania Railroad until 1865.

Carnegie first took notice of the profitableness of the iron business in 1864, when he bought a 1/6 interest in the Iron City Forge Company. In 1865 he organized his first business, the Keystone Bridge Company. For that enterprise he succeeded in placing stock in the hands of J. Edgar Thomson, president of the Pennsylvania Railroad; Thomas A. Scott, vice-president; and a number of other officials. At the same time the Superior Iron Company sought to build the Superior Rolling Mill at Manchester, near Pittsburgh, to make iron rails. Again Carnegie invested, brought Thomson and Scott into the deal, and they became actively involved.

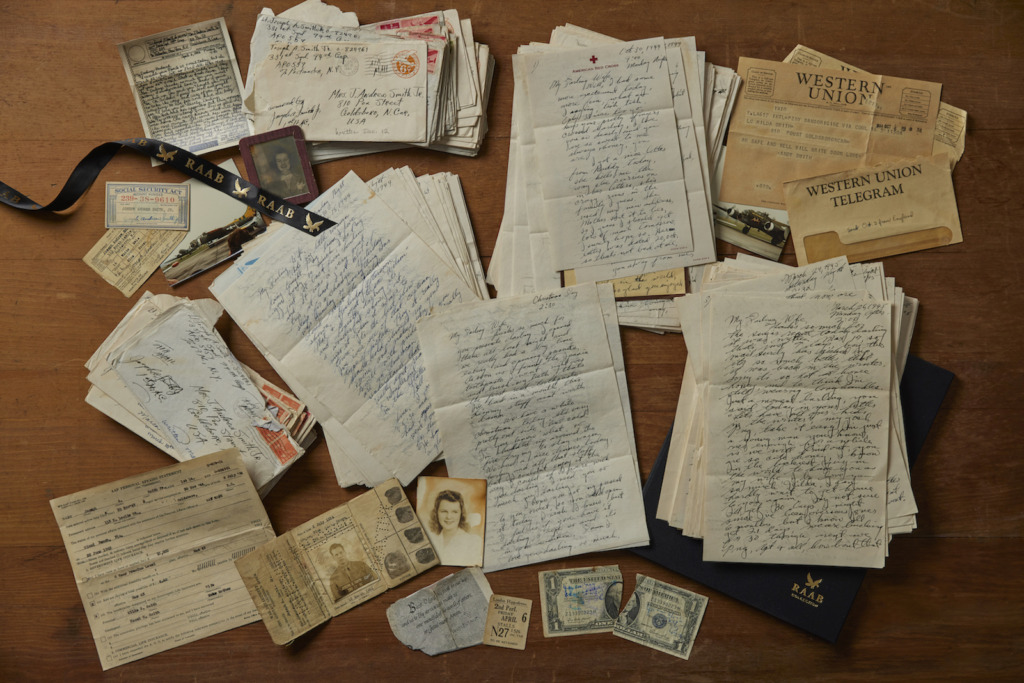

Autograph Document Signed, Pittsburgh, January 3, 1865, being a receipt made out to "Andrew Carnegie Esq., Trustee" for the sum of $2000 as the fourth installment "on 200 Shares in the Superior Iron Company." The recto of the receipt is in the hand of, and is signed by, John Scott, son of Thomas. On the verso Carnegie has written, "Received from J.E. Thomson the sum paid as here enclosed. A. Carnegie, Jany. 3/65." It thus appears that either Carnegie bought the stock on Thomson's behalf, or that Thomson lent the money to Carnegie to buy the stock and was given this receipt.

In March 1865 Carnegie resigned from the Pennsylvania Railroad and in May left the United States for Europe. This opening phase of his life came to an end. After he returned, his attention turned to steel, a process which he had learned of while traveling.

Documents from this early phase of Carnegie's career are very rare, this being our first. Moreover, a search of public records going back 40 years turns up nothing earlier than 1870.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services