In a Back Channel, Secret Communique During the Vietnam War, Senator Robert Kennedy Engages in Diplomacy With the Viet Cong to Free an American Prisoner

He writes the President of Algeria, in powerful language, referring to President John F. Kennedy’s fight in the “interest of peace for all the people of the world”

- Currency:

- USD

- GBP

- JPY

- EUR

- CNY

This incredible unpublished letter comes from the estate of the Algerian Ambassador to the United States and has never before been offered for sale

1965 marked an escalation in the War in Vietnam. On February 19, 1965, some units of the South Vietnamese Army launched a coup and were able to force...

This incredible unpublished letter comes from the estate of the Algerian Ambassador to the United States and has never before been offered for sale

1965 marked an escalation in the War in Vietnam. On February 19, 1965, some units of the South Vietnamese Army launched a coup and were able to force a leadership change. In response to this, National Security Council Director McGeorge Bundy and Secretary of State Robert McNamara wrote a memo to President Johnson. They gave the President two options: use American military power to defeat the Viet Cong insurgency, or negotiate thus attempting to “salvage what little can be preserved.” Bundy and McNamara favored the first option; Secretary of State Dean Rusk disagreed. Johnson accepted the military option and sent a telegram to U.S. Ambassador Maxwell Taylor in Saigon, saying “The U.S. will spare no effort and no sacrifice in doing its full part to turn back the Communists in Vietnam.” President Johnson had crossed the Rubicon.

On February 2, 1965, just before the coup, the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam, the official name of the group called Viet Cong in the U.S., kidnapped Gustav Hertz, Chief of Public Administration for the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) in Vietnam. Hertz’s captivity set in motion an intricate series of diplomatic gestures that involved several governments, including those of Algeria, Cambodia, and France, and numerous prominent individuals, such as Senator Robert F. Kennedy, Cambodian leader Norodom Sihanouk, and Algerian President Ahmed Ben Bella, in an effort to win his release.

On March 30, 1965, the U.S. Embassy in Saigon was bombed by the Viet Cong. One of the V .C. agents, Nguyen Van Hai, was caught, swiftly tried and condemned to death by the Saigon government. Both the clandestine Viet Cong radio station and Radio Hanoi immediately warned that if Hai were executed, Hertz would be too. Until a plan to free Hertz could be devised, therefore, the immediate problem was to keep Hai alive. That ran counter to the mood of the South Vietnamese government.

Each time Hai’s execution was scheduled, U.S. officials pleaded for a postponement. Chester Cooper, who handled the Hertz case for the White House, remembers one telegram from Ambassador Maxwell Taylor saying there was great pressure in Saigon from the police and the families of the bombing victims, and he did not think Hai’s death by firing squad could be delayed any longer. Somehow it was.

In June 1965, Prime Minister Nguyen Cao Ky came into office with the support of American officials, and he promised to carry out death sentences against all terrorists. Only under unremitting pressure from the U.S. ambassador did Ky reluctantly agree to exempt Hai.

While the Administration was concentrating on preventing Hai’s death, the Hertz family approached members of Congress for help. The first one contacted was Senator Robert F. Kennedy, who lived in nearby McLean, Va. The senator, after clearing with the Administration, paid a visit to an old friend, the Algerian ambassador, Cherif Guellal. In 1962 the National Liberation Front, political organization of the Viet Cong, had established in Algiers its first mission outside Vietnam. Would the Algerian government, Kennedy asked Guellal, consider intervening with the N.L.F. on behalf of Hertz?

The Kennedys had a unique relationship with the government of Algeria, which had just received its independence. As early as 1957, John F. Kennedy had taken the floor of the U.S. Senate and given a speech that denounced France for its colonialism in Algeria and called for Algerian independence. He had even introduced a resolution to that effect. When Algeria obtained its independence in 1962, Kennedy, then President, issued a moving statement: “This moment of national independence for the Algerian people is both a solemn occasion and one of great joy. The entire world shares in this important step toward fuller realization of the dignity of man. I am proud that it falls to me as the President of the people of the United States to voice on their behalf the profound satisfaction we feel that the cause of freedom of choice among peoples has again triumphed.” So the Kennedys had the ear of Algeria.

The same day Guellal met with RFK, he telephoned Ahmed Ben Bella, Algeria’s president, who consented to try to liberate Hertz. Within a few days, Guellal reported back to Kennedy that the N.L.F. representative in Algiers, a onetime guerrilla fighter named Huynh Van Tam, had said his organization would agree to an even exchange – Hertz for Hai. The Algerians further reported that Tam had voluntarily extended their discussion to include all prisoners then held by the Viet Cong, military as well as civilian, saying their willingness to divest of prisoners was because the V.C. had to move so swiftly around the countryside. Even the matter of the logistics of a Hertz-for-Hai swap was discussed. One plan was to ask Senator Kennedy to come to Algiers, where Hertz would be handed over to him. “I am convinced,” Ambassador Guellal said later, “that the N.L.F. was very, very ready.”

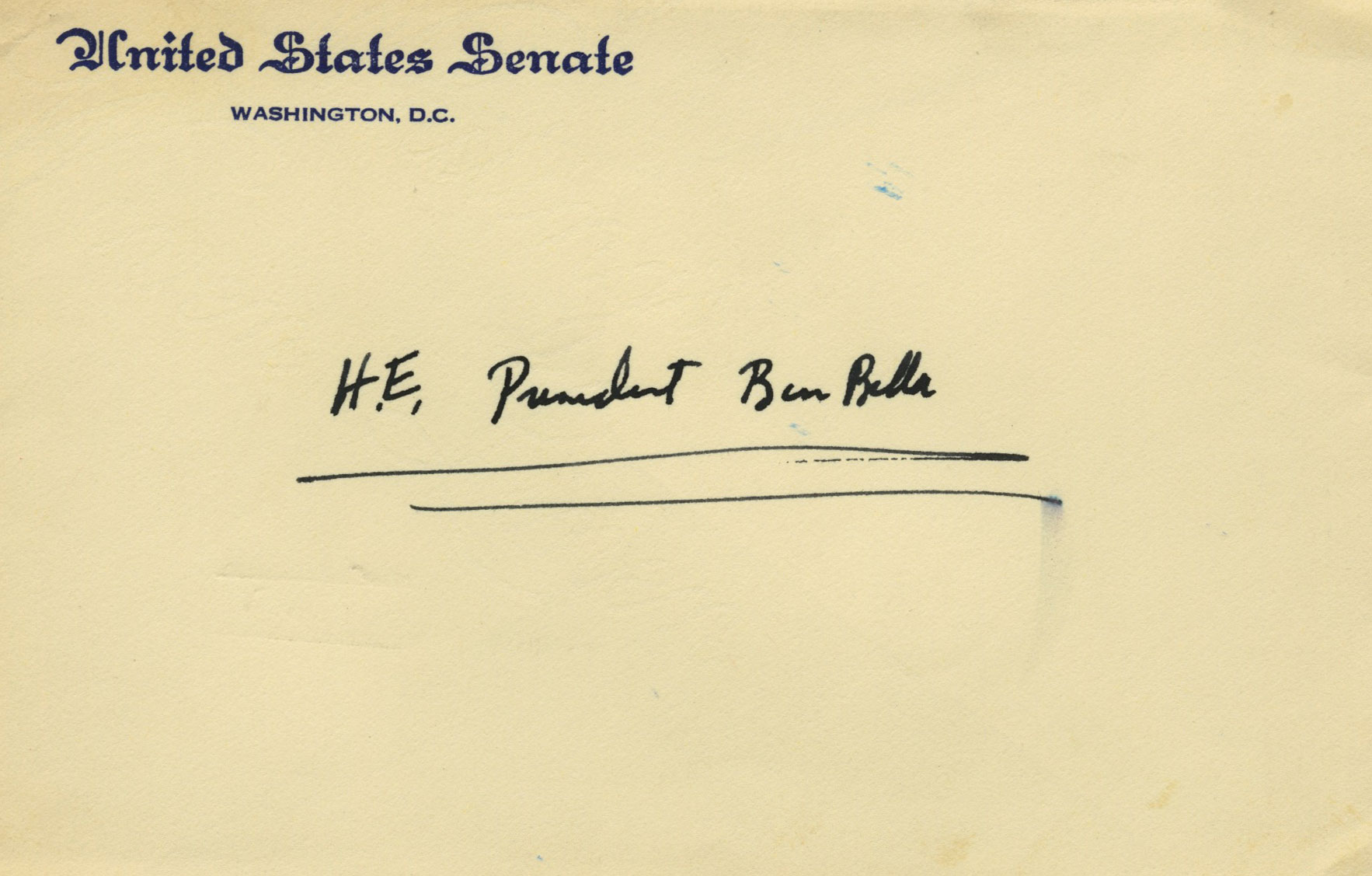

This letter is Robert Kennedy’s original response to his invitation to Algeria, hand delivered to the Algerian Ambassador to the United States.

Autograph letter signed, on Senatorial letterhead, June 1965, to the President of Algeria. “Dear Mr. President. I send you my best wishes. I believe that you and President Kennedy working together were able to accomplish many things for the peoples of both our countries, but also in the interest of peace for all the people of the world. I know even without him that you will continue that effort.

“My appreciate to you for the discussions with your Ambassador. I am grateful for your invitation to visit Algeria and would very much like to come.

“The Kennedys have always had a strong feeling of affection for you and your people. Respectfully Robert Kennedy”

This unpublished letter comes from the estate of Ambassador Guellal and has never before been offered for sale.

As for the Hertz-for-Hai exchange, it never happened. Senior officials in Washington ended up feeling that freeing Hai would send the wrong message to the South Vietnamese at a moment when escalation of the war was the number one priority. Both men remained in prison. At the end of the war, in 1973, Gustav Hertz’s name appeared on a list delivered to the U.S. government of Americans who had died in captivity in Vietnam. He had not been executed, but had died of malaria in a North Vietnamese prison.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services