Henry Clay Takes a Stand on the Slavery Expansion: The South Should Concede the Issue

The Great Compromiser’s premonition of Civil War: If no agreement is found between the North and South on slavery, “I think the future full of uncertainty.”.

He is pressured to support Zachary Taylor in the 1848 presidential against his wishes, warning that Taylor is an unknown quantity who may “totally disappoint Whig hopes”

The question of the annexation of Texas was one of the most controversial issues in American politics in the late 1830s and early 1840s. Texas...

He is pressured to support Zachary Taylor in the 1848 presidential against his wishes, warning that Taylor is an unknown quantity who may “totally disappoint Whig hopes”

The question of the annexation of Texas was one of the most controversial issues in American politics in the late 1830s and early 1840s. Texas would be admitted as a slave state, and the real issue was thus not Texas but slavery, at least originally. The admission of Texas to the Union would upset the north/south sectional balance of power in the U.S. Senate, and provide slavery a huge new place to grow. Congress and the country were deadlocked. But the Texas question opened the door to a movement in the United States that claimed expansion to be its “manifest destiny”. The 1844 election became about annexation, and also about “manifest destiny”.

Henry Clay lost the 1844 election, his third shot at the presidency as the Whig Party nominee, to an aggressively expansionist Democratic nominee, James K. Polk, as a result of his equivocation about annexation and expansion. He was astride the fence like that because most Whigs opposed both annexation of Texas, which would mean an additional slave state, and manifest destiny. Then in 1845 came the Mexican War. Many Whigs, such as Abraham Lincoln and Daniel Webster, opposed annexing Texas and going to war with Mexico. Some did so simply on moral principles, thinking it an unprincipled land grab; while others feared that much of the territory the United States would gain would become open to slavery (and strengthen that institution and the Southern states); and still others opposed expansion because of concerns that adding new states would decrease the political power of the states they lived in and represented. Many Whigs tapped dance through the war, seeking to oppose the war while still supporting the troops, and wanting at all events to avoid being seen as unpatriotic.

The Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo ending the war arrived from Mexico in February 1848, and provided that Mexican lands north of the Rio Grande would be ceded to the United States. The treaty posed an anguishing problem for the Whigs. It brought the peace for which they had clamored, yet it entailed the territorial acquisition so many of them had opposed and even feared. In the end, the Senate somewhat reluctantly ratified the treaty on March 10 by a vote of 34 to 14, with the Whigs split. The admissions of California and New Mexico as states would be decided during the summer. But more important was the question of whether Congress and the country would be able to find an overall resolution to the slavery issue, so as to make these expansion decisions palatable and avoid a deepening confrontation between north and south.

In 1848 Clay expected to be nominated, and with Polk too ill to seek reelection, thought he would be able to win. Both of the major parties hoped to avoid the slavery issue's divisiveness in 1848. However, many Whigs saw no hope of success by nominating Clay a fourth time, and promoted the nomination of General Zachary Taylor, a Mexican-American War hero. Taylor was nominated on the four ballot, and Clay was resentful. The Democrats turned to Lewis Cass of Michigan, a colorless party loyalist. Cass advocated popular sovereignty on the slavery issue, meaning that each territory would decide the question for itself – a stance that pleased neither side. Taylor, who had no political experience and had never voted, was elected in November.

In the extraordinary following letter, Clay stakes out a position against the expansion of slavery, something he had previously tried to squirm out of doing, predicts that lack of North/South agreement over slavery expansion will have repercussions, and that if there is no agreement, he is worried about the future. He denounces those who make slavery the only important issue before the country. He states that the Whig Party is not pro-war, claims that Gen. Winfield Scott had wanted to be his 1848 running mate, knowledge of which would have won him the nomination, and assigns blame for his loss of the nomination. He also discusses the upcoming presidential election, saying that he is being pressured to support Taylor against his wishes, and warns that Taylor is an unknown who may disappoint.

His additional named references in the letter are: Ex-President Martin Van Buren, who was running on the anti-slavery Free Soil ticket; Gen. Winfield Scott, a hero of the Mexican War who would himself be the Whig Party nominee in 1852; Joseph Vance, a Whig Congressman who was been the first Whig governor of Ohio, and was known for his views against the annexation of Texas and the Mexican War; Garnett Duncan, a Kentucky Whig Congressman; Lewis D. Campbell, an Ohio Whig Congressman; and George Robertson, a Kentucky judge. The Barnburners and Hunkers were opposing factions of the Democratic Party in New York, the former more radical and the latter more conservatve.

The letter’s recipient was Thomas B. Stevenson, a diehard Clay supporter and editor of the Marysville (KY) Eagle newspaper. Following receipt of this letter, Stevenson wrote a lengthy letter justifying Clay to the New York Tribune on August 24. It is published in The Works of Henry Clay.

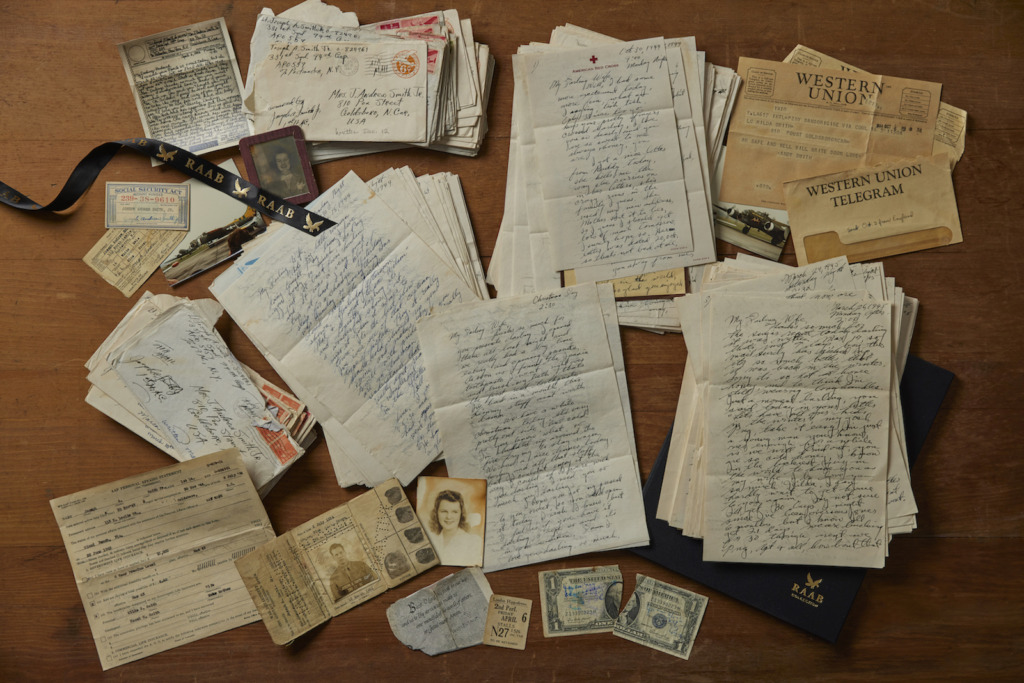

Autograph Letter Signed, two pages, Ashland, Lexington, Kentucky, August 14, 1848, to Stevenson, and marked "Private”. “I am extremely sorry to learn by your letter of the 10th inst. the alarming illness of your child, which i sincerely hope may be spared to you, notwithstanding your fear. My friend in Ohio (Mr. Van Tromp of Lancaster) attributes to Vance the controlling influence which determined the course of the Ohio delegation; he himself being gained over by the influence of the Congressional clique at Washington. That is now my opinion. With that view he forwarded on the 20 delegates to go together, and to promise that none would break unless all did so. With that view, also he opposed, as Mr. Campbell states, any appointment of a committee to confer with delegates from other states. I suspect that the distinguished friend of mine, as Genl. Scott calls him, to whom he communicated his willingness to run as Vice President on a ticket with me, was G. Duncan, who was in New York about the time of the General’s arrival from Mexico. Genl. Scott's letter to me is not marked private nor confidential; and I think you might say, in your letter to the Tribune, 'that you have had the most satisfactory evidence that General Scott was willing to run as a candidate for the Vice Presidency on a ticket with me, and that that fact was not disclosed to the members of the Philadelphia Convention by the member of Congress who was authorized to make it known.’

"The retrocession of New Mexico and California, I did not suppose to be at present practicable; but if the question to which they have given rise should long remain unsettled, and the existing excitement and agitation should continue and increase, I should not be surprised if public opinion should finally take that direction. If the South were wise, it would yield the point in dispute, even if, contrary to my opinion, it [the best argument] was with her. In the meantime, many of the friends of the principle that free territory should remain free, are putting themselves in a position full of embarrassment. They think that it is the great question of the day, overruling and suspending all other questions. How then can they vote against a presidential candidate who agrees with them, and for another who differs from them, on that paramount question? I, who do not attach the same importance to that question, feel no such embarrassment.

“I am excessively bound (even from Ohio!) to come out and endorse General Taylor. As if he had not spoken in a way that all may comprehend him! As if it were not enough that I should submit quietly to the decision of the Philadelphia Convention! Suppose I could endorse him, and being elected, he should totally disappoint Whig hopes, would I not be justly liable to the reproaches of any one that I might have misled?’ North Carolina was one of the states which was to have gone for him by spontaneous combustion. And what has she done? Gov. [John M.] Morehead told Judge [George] Robertson that it would have given me a majority of 12,000. The Whig clique at Washington totally mistook the character of the Whig Party, as it once was. You have correctly described it. It is not a gun-power party.

"If Congress has risen without an adjustment of the slave question, I think the future full of uncertainty. Mr. Van Buren, will, I believe, get a much larger vote than is now imagined. The Whig party at the North and in Ohio is much more imbued with the anti-slavery feeling than the Locofoco party, and in all of the states except New York, he will make upon the former the larger inroads. I should not be surprised if many of the Old Hunkers in New York unite with the Barnburners and the dissatisfied Whigs to give the vote of that State to Mr. Van Buren, and thereby indirectly promote the interest of General Cass. But I cease with speculations.” Docketed on the blank verso.

The South did not take Clay’s advice and concede, and by 1850 agitation on both sides of the slavery issue became even worse. On January 29, 1850, Clay introduced a series of resolutions known as the Compromise of 1850, in an attempt to avert a crisis between North and South. The measures past, but Civil War was on the horizon. Clay did not live to see it, dying in 1852.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services