The Nation’s First Attorney General, Edmund Randolph, Defends Himself Against Accusations of Personal Impropriety While Serving in Washington’s Cabinet

The allegations were made by Benjamin Harrison, Jr. and regarded the estate of Continental Congress President Peyton Randolph.

“You speak of a supposed secrecy in the transaction… the truth is that the bargain was a topic of general conversation here…I have never handled a shilling of the money of the estate of Mr. Randolph; nor do I ever intend it…My engagement is founded upon my own estate not the estate...

“You speak of a supposed secrecy in the transaction… the truth is that the bargain was a topic of general conversation here…I have never handled a shilling of the money of the estate of Mr. Randolph; nor do I ever intend it…My engagement is founded upon my own estate not the estate of Mr. Randolph…But you will pardon me for adding that I hold myself justified in this transaction so strongly that nothing would have drawn better from me but my ardor to place every thing upon its proper footing.”

Peyton Randolph was President of the First and Second Continental Congresses, until he resigned because of illness. His successor was John Hancock. Randolph was married to the sister of Benjamin Harrison, a Signer of the Declaration of Independence, and his nephew and one of his heirs was Edmund Randolph, who in 1789 became the first Attorney General of the United Staes. Upon Peyton’s death in 1775, Harrison and his son, Benjamin Harrison, Jr. became executors of his estate, a position to which Edmund would also be named. Some of Peyton’s estate was auctioned in 1783, after his wife’s death. Randolph family cousin Thomas Jefferson bought his books, among them bound records dating to Virginia’s earliest days that still are consulted by historians. Added to the collection at Monticello that Jefferson sold to the Federal government years later, they became part of the core of the Library of Congress. But part of Peyton’s estate still had assets and debts in 1790.

Judge Henry Tazewell was a creditor of Peyton’s estate. He and Benjamin Harrison Jr. wanted to become the mortgage holders on one of Peyton’s properties, and Harrison tried to change arrange a transaction to reflect that. But Edmond Randolph prevented it, saying that no single executor could make that change. Harrison was none too pleased.

Peyton served in the French and Indian War with Col. William Byrd, and they remained friends. After Byrd’s death, the Randolph family were advisors to Byrd’s children and involved in their financial dealings. The Randolphs clearly felt some responsibility to the Byrds and became involved in what was in effect a life insurance policy on some of them. Tazewell had an obligation to pay $4000 to the estate of the Byrds when they died. Nathanial Harrison of Brandon offered that for $200 paid in hand by Tazewell now, he would take over that obligation. Tazewell ended up agreeing to assume debts against the Peyton Randolph estate in return for which Edmond Randolph took over the obligation to pay the Byrd estate.

Benjamin Harrison, Jr. then accused Randolph of acting improperly and secretly in handling the assets and liabilities of Peyton’s estate, and making the deal to provide financial benefit to himself and in effect violating his fiduciary duty to the estate. He demanded that Randolph resign as executor, which was a threat to Randolph’s reputation. Randolph responded that his dealing were proper and no secret, that he had never handled a nickel from his uncle’s estate but had the right on his own account to undertake with a potential future debtor to secure him against any such debt. He then explained that he could not resign even if he wanted, defended his conduct, and insisted on an immediate resolution. After all, if his reputation was tarnished by wrongdoing regarding his uncle Peyton’s estate, Virginians George Washington and Thomas Jefferson would find out immediately, and he would have to resign as Attorney General in disgrace.

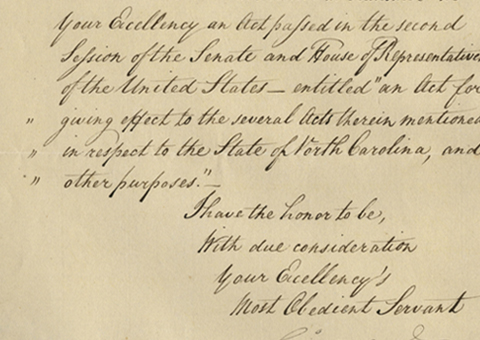

Autograph letter signed, Williamsburg, June 21, 1790, to Benjamin Harrison Jr. “Dear sir, I am sorry that any transaction of mine should have interrupted your attention to your little boy, whose safety is so near to your heart. But as what I have done never would have been done had I doubted its propriety, so shall I not hesitate a moment in relating it to you.

“About four years ago, or perhaps more, Mr. Tazewell informed me that you and he were negotiating for the mortgage and meant to accept for some purpose or other which I do not recollect a payment by discount to change the security. The subject was mentioned to me for my approbation. I then declared as I still declare that one executor had no right to make such change. I never heard more of it myself until the last day or March last in the stage. He then observed that Mr. Harrison of Brandon would for 200 pounds paid to him now undertake to discharge him from $4000 at the death of Mr. and Mrs. Byrd. But no conversation passed between us on the subject. When he was about to leave the Richmond circuit, he wrote to me concerning a demand which Mr. Robert Carter had against my uncle’s estate; and supposing that it might be inconvenient to him to pay such a sum he offered me the terms which I have stated above. We postponed any thing definitive until he returned home. It was then agreed upon his paying for me 1742 pounds 17 shillings and 6 pence by assumpsits of certain debts that I would indemnify him against double that sum without interest within 20 days after the death of Mr. and Mrs. Byrd. The bargain was concluded in Richmond.

“And now after this statement of facts, give me leave to make some more particular observations.

“1. You speak of a supposed secrecy in the transaction. It would have given me no discoloring to it, in my judgment, had Mr. Tazewell and myself been the only persons to whom it was known. I did not, nor do I, consider myself any more bound to communicate this affair to any body else than I should be to communicate any money contract whatever. However the truth is that the bargain was a topic of general conversation here and was not avoided to be represented even in Richmond. I am very sure at least that I did not care who knew it and that I should have been equally free upon it if a seasonable opportunity had arisen in discourse as upon any other business which related to myself. When I saw you at your house I might perhaps or might not have informed you if we had not been interrupted by the coming in of Mr. Giles. But if I had done so it would have been merely in that style in which one acquaintance opens his affairs to another. I never saw you again but in the street when I told you the probably time of my departure. Having omitted it altogether I do not discover an objection to the omission.

“2. I have never handled a shilling of the money of the estate of Mr. Randolph; nor do I ever intend it. But this does not debar me from undertaking to a future debtor of that estate to secure him against his debt out of my private fortune.

“3. I have never seen the mortgage or any paper relating to the purchase of Kingsmill. My engagement is founded upon my own estate not the estate of Mr. Randolph. Nor is the security in my view changed. I wish I had a copy of the agreement with Mr. Tazewell. But I shall make it a point after what you have written to wait his return, obtain a copy of it, send it to you, and wait also for a letter from you concerning it. This I engage to do not from a sense that it is demandable of me but from a wish that no misrepresentations may take place after I have left the state. Nay more, upon this same ground, I will not leave the state until such communications shall have passed between us as shall either prove satisfactory or upon their being declared otherwise by you until you shall have a complete opportunity of taking any steps legal or equitable that you might choose.

“4. You will know that I qualified as an executor with no design to act. And if there were a practicable way of withdrawing myself from executorship and guardianship I would cheerfully embrace it. I cannot conceive any reason which would cause me to hesitate a moment about it but an expression in your letter which requests me to withdraw from both characters. I can assure you that my continuance in them springs from the difficulty of extricating myself from them and not to render them subservient to any purpose which is not honorable. My intention was to have obtained from Mr. Hanson a part of the bond due from the Wilton Estate and to have kept it on interest until Mr. and Mrs. Byrd’s death. I wrote to him upon this business and received his answer in the negative many days before I left this place for Richmond. So that when I suggested proposals of accommodation, I did so without any regard to myself. But I shall feel myself at liberty to provide for these deaths in the best manner in my power and my object is to procure 1700 pounds from a creditor for the estate which is due now and to keep it up or if it should be paid off in the mean time, to put it out to interest. My next design is to insure the lives of Mr. and Mrs. Byrd for 20 years. With these things however the estate has no concern and my engagements will have no tincture of either executor or guardians.

“I have thus answered I believe part of your letter. The postscript being only an extension of the idea of secrecy I shall make no further reply than I have already made. But you will pardon me for adding that I hold myself justified in this transaction so strongly that nothing would have drawn better from me but my ardor to place every thing upon its proper footing before I leave the country. P.s. I hope to hear from you by the stage. Be so good as to show this letter to Capt. Singleton and your sister as well as the governor….”

This is not only a rare ALS of Randolph as Attorney General, but one of great significance to him. He used all of his skills in framing it, and they are on display here. We obtained the letter directly from the Benjamin Harrison descendants, and it has never before been offered for sale.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services