The Unpublished Frontier Account of Anna Baker, Educator to the Sioux Boys and Women, A Rich, Historically Significant Account, Powerfully Told

Her account of life at the Yankton agency, her and others' pioneering efforts at education and detailed, often poetic accounts of events and incidents with the Sioux and Ponca populations

Note on provenance: This was passed down with the Gregory heirs and has never before been offered for sale.

Note on rarity: We are unable to find another such an important first hand account from an important female pioneer having reached the market

These original photographs come with the archive...

Note on provenance: This was passed down with the Gregory heirs and has never before been offered for sale.

Note on rarity: We are unable to find another such an important first hand account from an important female pioneer having reached the market

Educational and religious pioneers she discusses: among them Missionary JW Cook, Agent Rev. John Gasmann, Sister Lizzie Stiteler, linguist Rev. Samuel D. Hinman, Rev. J. Owen Dorsey, Bishop Hare and St. Paul’s School for Indian Boys. She also discusses the construction of the pioneering school for girls.

Prominent Native Americans: Red Cloud, Flying Pipe, and Chief David Tatiyopa, as well as Sioux Chief Deloria, whose conversion she describes in detail.

Life of a woman on the reservation: There is a huge amount of first person information on the life of women as teachers and students. She goes to great lengths to break out the roles played by women in the Natives’ cultures, and also describe her life as a woman and the other women around her.

The service for Chief Deloria: “The Sunday services are most interesting. Scarcely one passes without one or more baptisms, some of infants and many of all ages. An old Chief, Deloria, who has been long considering the duty of giving up all save one wife and then of being publicly married to her, at last asked to have the ceremony performed and before a congregation of curious or sympathetic witnesses. The old chief and his wrinkled but smiling old wife responded clearly as directed. One of the sons of the couple, Philip Deloria, is a remarkably fine fellow of about 21 years who already possesses a fair education and is planning to become a minister to his people.”

A new school for boys and another for girls: “St. Paul’s school is a reality, Mrs. Duigan being house mother and the Rev. Henry St. George Young house master. There is already quite a number of boys gathered there and they are to be taught to do house and garden work as well as handle book and slate. This building is to have a large two story addition running out from the western end of the church and here a boarding school of 20 girls to be established.”

Attempting to engage the women of the reservation: “One school is doing fairly well and some days are really quite encouraging. Dear Mrs. Gasmann has helped me organize a sewing school to meet Saturday afternoons in the church and though but six timid women came in response to the first invitation we are convinced the numbers will increase.”

The burial of non-Christian Sioux: “On top of this scaffold the body was laid in its wrappings and secured firmly in place, then the pony was led so as to stand directly underneath his master then and there killed by a host which we distinctly heard. The body of the pony will be left there as it felt and daily some friend will carry a small quantity of food and place it on the scaffold that the spirit of the man may still ride and feast as of old”

From the earliest days of the Republic, administrations recognized the importance of having a structure to treat with Native Americans, and agents were designated for this purpose, given the roles of protecting and promoting commerce, managing treaties, and, in later years, distributing rations and teaching what were considered “civilized” skills. Until 1849, this job was performed by the military, under the auspices of forts and agencies, sometimes at reservations, when such reservations were established. In that year, authority was wrested from the military and given over to civilian control in an effort to ensure qualified and moral agents. In 1869, a Board of Indian Commissioners was created to exercise that civilian control more effectively. Moreover, when U.S. Grant became president, he brought to the enterprise a belief that religious leadership had proven effective in establishing productive and peaceful relations. His 1871 State of the Union said: “The policy pursued toward the Indians has resulted favorably … many tribes of Indians have been induced to settle upon reservations, to cultivate the soil, to perform productive labor of various kinds, and to partially accept civilization. They are being cared for in such a way, it is hoped, as to induce those still pursuing their old habits of life to embrace the only opportunity which is left them to avoid extermination.” The emphasis became using civilian workers (not soldiers) to deal with reservation life, especially Protestant and Catholic organizations.

Women played an important and underappreciated role in the life of the Agency. Baker and the women who joined her were pioneers. And she describes the creation of a girls boarding school for Native American girls.

The Sioux Native Americans were one of the great plains tribes, or rather a collection of three related tribes, one of which being the Yankton Sioux. The majority of these Sioux moved on to their new reservation in the 1860s and were fairly hostile to other neighbors, among them the Ponca, a smaller tribe who had for a brief time their own agency not far away. Both were in South Dakota. These agencies were a symbol of a larger civilian reservation management period, one in which the mandate for these agents expanded and incorporated a clearer religious and even educational component.

In the 1860s, John Shaw Gregory, grandson of naval hero John Shaw, and Francis Hoyt Gregory went West. JS had his own military career, which had begun as a young shiphand on board the slave hunting vessel The Raritan in the South Atlantic, sitting off Brazil and looking for vessels heading north and west. Shaw served as one of the first agents to the Ponco, if not the first. He called East for his brother, Henry E. Gregory, who followed him West to South Dakota, following his appointment by Grant himself as agent to the Ponca Indians. Henry had been promoted during the Civil War by Abraham Lincoln.

Two years later, in an unrelated event, Anna Baker, a young woman with a broken engagement, gave up her life in New England to become a teacher to the Native Americans. She spent a brief spell with family and friends in Sioux Falls, before heading even farther West, by steamboat and stage, to take her place at the Yankton agency. There she would be one of the first formal educators under this new Native American regime. She was a pioneer, and she joined other pioneers, among them Missionary JW Cook, Agent Rev. John Gasmann, Sister Lizzie Stiteler, linguist Rev. Samuel D. Hinman, Rev. J. Owen Dorsey, Bishop Hare and St. Paul’s School for Indian Boys, prominent Native Americans like Red Cloud, Flying Pipe and Chief David Tatiyopa, as well as Sioux Chief Deloria, whose conversion to Christianity she describes in detail. There is a huge amount of first person information on the life of women as teachers and students. She goes to great lengths to break out the roles played by women in the Natives’ cultures, and also describe her life as a woman and the other women around her.

She witnessed many things that most European descendants never would. And she kept a daily journal. The contents of that journal have evidently never been published before now. They tell of death, disease, attack, hardship, but also of education, love, baptism, gossip, and the nature of life as a woman on the reservation in this early period.

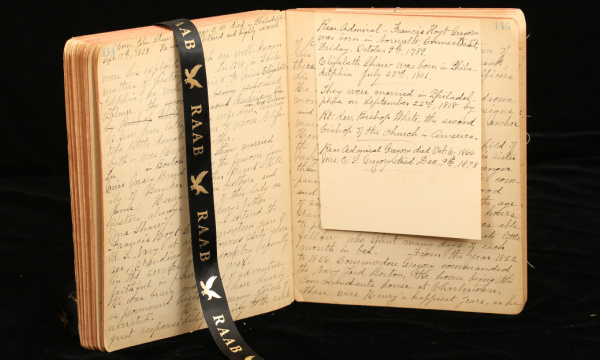

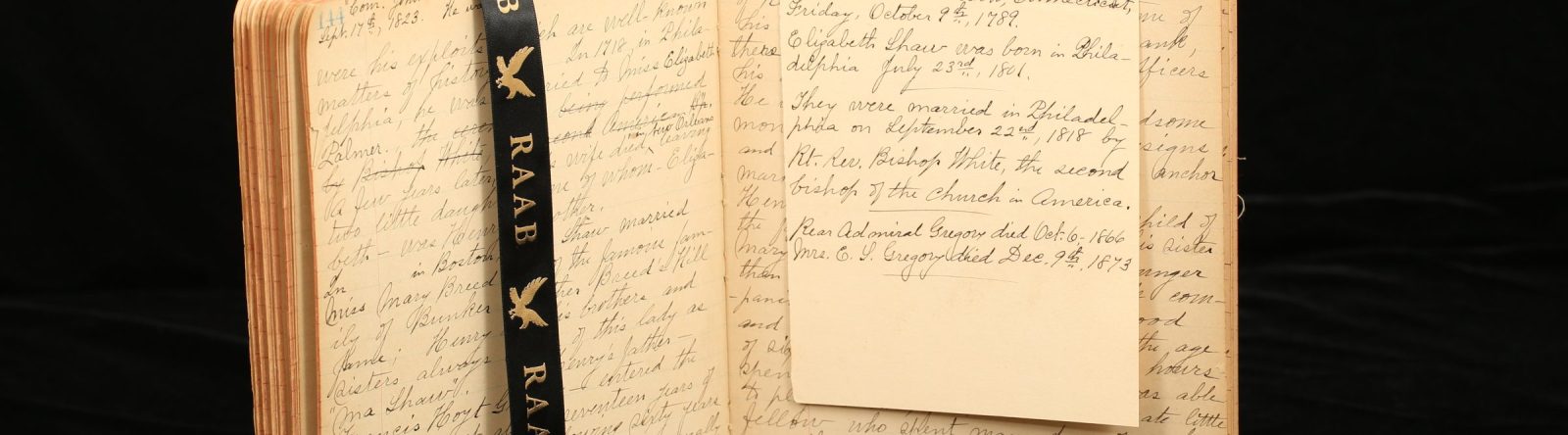

The Sioux reservation account, as a diary, of Anna Gregory, kept after her return east, dating 1872-1938, consisting of 160 pages of dense writing. The pages or organized as follows:

Page 1-18 – A detailed and unsparing history of the Baker family and its offshoots, a valuable genealogical resource

Pages 19-133 – The first person diary

Pages 134-142- No content

Pages 143-168 – A detailed biography of the life of her husband Henry

Based on the uniform nature of the script, the first person pen of Anna, and other factors, this is almost certainly a copy created by Anna for her son Harry, who would die before her. The original of the journal written in the 1870s then has likely been destroyed, as instructions from her indicate, this being the only source now for the content which would otherwise be completely lost. It therefore begins: “This book is the property of Harry Baker, Sioux City, Iowa, June 10, 1904.”

What follows is a 17 page biography of Anna Baker’s family, leading up to her birth. It ends: “Now we will let Anna tell the remainder of her story herself.” (page 18)

The journal, a very small selection

Page 19 is the first page of the day-by-day, first person entries. A broken engagement had sent her to see family in Iowa. It begins April 8, 1872, Davenport, IA. “Now for it! Truly here is a turning point in my life… I am a young woman, of twenty-five years, possessing perfect health, a good education, many friends but no money to speak of. My parents died when I was young and my brothers and sisters all much older than myself have raised me with abundant love and affection…” (page 19)

“I have arrangements all made to go to an Episcopal Mission to teach the Sioux Indians in Dakota.” (page 20)

Arrangements to get West and travel were more complicated. She had evidently not seen a steamboat in operation before. From April 1872.

“There is no rail road extending beyond Sioux City, transportation being by stage and freighting teams or through the season of navigation by steamboats on the Missouri. And such boats! The odd things have one immense stern wheel as propelling force, churning volumes of the foaming, muddy water as they crawl up or glide more rapidly down stream. Interest of all to me, however, are the great spars with joints at the top, reminding one of grasshoppers legs. The spars are placed at the boat’s bow and so constructed that when the boat runs aground on one of the ever present sandbars the signal is promptly given to swing out the lower ends of the spars, plant them firmly in the sand of the bar and pry the boat free….There is expected hourly to arrive from St. Louis a large side-wheeler, the Mary McDonald, which carries passengers and freight to points further up the river.” (22-23)

She became fast friends with the Gasmanns from Norway. He was an Episcopal clergyman and Indian agent: “Very large, blond, blond man, reminding one of the Vikings of Norway…. Mrs. Glassman too is large, a brunette, a sister of Bishop Clarkson of Nebraska.” (24)

“We are by this time quite accustomed to the monotonous calls of the men who sound for depth of water. One is stationed on the lower deck with plummet and line to ascertain the depth of the water on the most doubtful side; this man’s long drawn call of perhaps “six and a half, six feet,” “five feet” etc. is repeated in the same drawling tone by a second man placed at the rail just above the first and thus is heard by the pilot in his letter wheelhouse.” (26)

She arrives at the Ponca Agency.

“Our arrival was a big event to the natives and we had a chance to see Indians large and Indians small crouching on the very edges of the crumbling bank, near as possible to the great ‘wata peta’ or ‘fire boat’ one of the first of this season to greet their eyes…. The figures of all ages stood or sat motionless and closely wrapped in dirty shawl or blanket, often up to their eyes which saw everything. About three hundred men, women, and children were grouped about our landing…Two white men were visible, one a laborer and the other a tall slender gentleman – Major Henry E. Gregory [future husband], the government agent for the Poncas, and who with his negro service man [someone has written in here John Williams], had his home in a very comfortable though plain frame house back a block or more from the river bank.” (April 26 1872, page 27)

She pushes on to her destination at the Yankton Agency

“The wind was blowing furiously, as we are told it generally does in Dakota, though there was brilliant sunshine to welcome us, and yes there upon the bank was the missionary, Rev. JW Cook, with a few other white persons and a small gathering of Indians.” (April 27, 1872, page 30)

She provides a description of Yankton.

“A short distance from the bank of the river, perhaps half a city block, stands the agent’s residence, a very comfortable looking frame dwelling painted white with green blinds, one large room being used as office, while a little nearer the river are located numerous ugly buildings, some of logs, with earth roofs and others framed, all unpainted. These are the various workshops and store houses built and utilized by the US government. Facing the river stands the store, whose stock they tell me consists of a medley of all sorts of goods from candy and chewing gum to farming implements and household furnishings. The trader has his dwelling over the store.” (same date, page 30)

And a description of the church tract.

“Mr. Cook kindly pointed out to me various features of the mission tract. The combined church and house (dwelling) really looked quite attractive, the house 1 1/2 story of logs being attached to the frame church whose tower contains a large bell. A neat fence encloses all the mission grounds, while on the bluff, further in the rear, a cemetery has already been laid out. To the westward, perhaps another block distant, are the detached church and dwelling of the Presbyterian mission. One entering the mission house we were greeted by an old lady ‘Auntie West’, whose life for many years had been spent in teaching the Indians in Minnesota under Bishop Whipple before coming here a few months ago. A bright eyed young woman, about my own age, Sister Lizzie Stiteler, added her welcome and a shy little boy of 9 years – a waif whom Mr. Cook had found and adopted in Wyoming…. Only a few [Indians] lived within sight of the Agency proper, there being here and there a log house in sight, as their homes were scattered for miles all over the reservation. On one day of each week – Ration Day – they come trooping in to the store houses for their week’s supply of food.” (same date, page 32)

Her room with Sister Lizzie.

“There is a comfortable looking double bed which I am to share with Sister Lizzie, while Master Willie has a pallet on the floor in one corner, my trunk looms up in another and around the eaves closely packed are boxes and bags of tea, crackers, sugar and other necessaries of life for which there seems to be no other available refuge. Where can one find a moment’s privacy? I am writing now in the living room down stairs with talking going on about me. Can I accomplish my real good for any soul by leading this life?” (same date, page 35)

She attends her first church service with the Sioux.

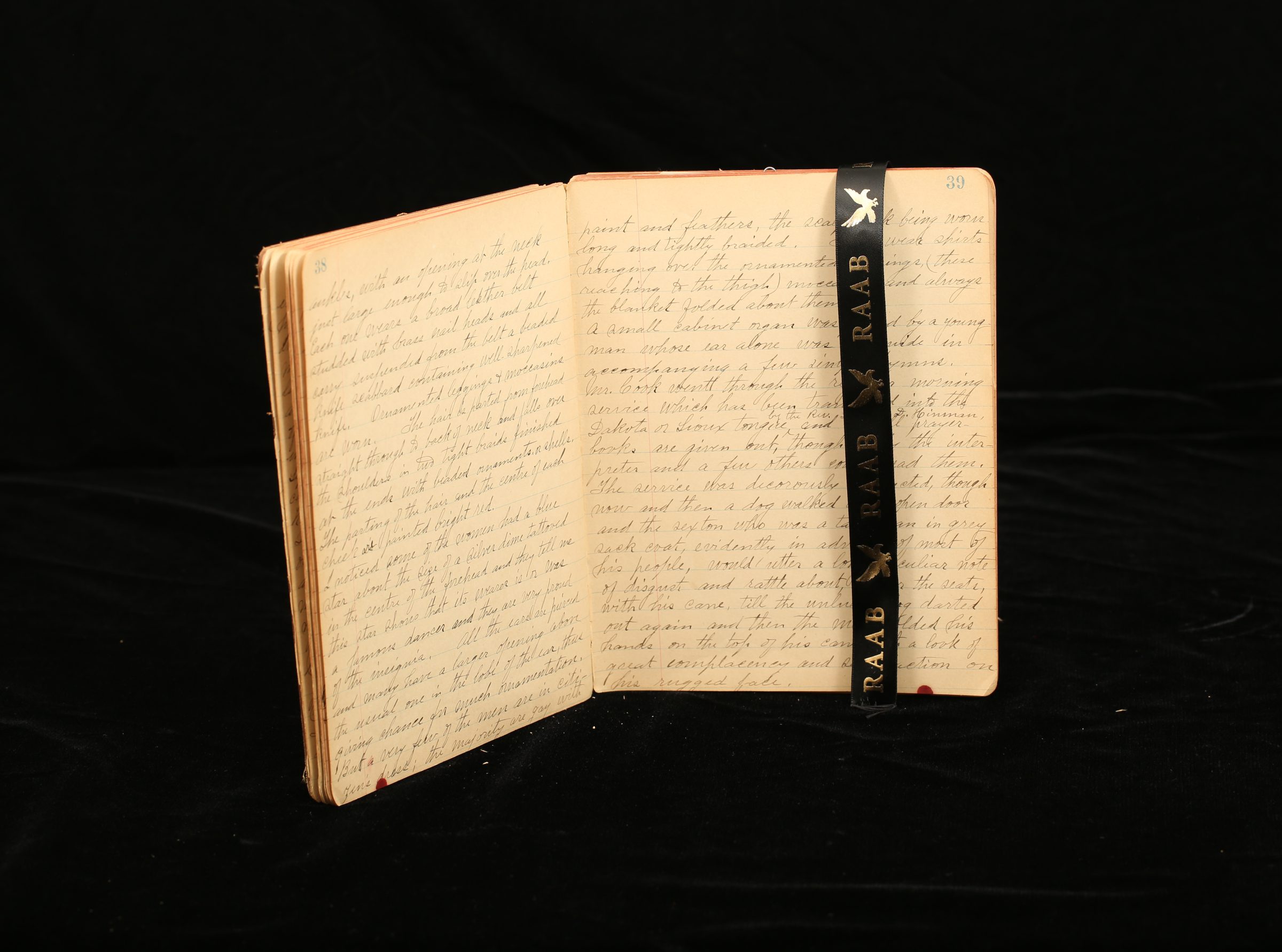

“Mr. Cook has been here with the Sioux but a year and a half but has already such a command of the language that he seldom requires an interpreter save in delivering sermons. An early communion service was held for the mission family and by nine o’clock the bell was rung hastily though the Dakota service began at 10:30. Considerable ringing and tolling of the bell seemed necessary in order to gather them in. Most interesting it was to me to watch the gathering from all directions. Women with pappooses on their backs, the little black head bobbing about contentedly over the mother’s shoulders came walking or on horseback, sitting astride. There were many lumber wagons drawn by a pair of sturdy little ponies carrying whole families. In church the women and small children all occupied the motherly half of the space, while the men and larger boys strode into the other rows of seats with lordly airs. The women and girls seem to be very modest; seldom is the shawl or blanket dropped off the head though they enter heartily into such parts of the service as have become familiar to them. The women wear straight calico dresses, not reaching to their ankles, with an opening at the neck just large enough to slip over the head. Each one wears a broad leather belt studded with brass nail heads and all carry suspended from the belt a beaded knife scabbard containing well sharpened knife. The hair is parted down the forehead straight through to back of neck….I noticed some of the women had a blue star about the size of a silver dime tattooed in the centre fo the forehead and they tell me this star shows that its wearer is or was a famous dancer… All the ears are pierced and many have a larger opening above the usual one in the lobe of the ear….” Much more on this subject. (April 28, 1872, page 37-8)

“A small cabinet organ was played by a young man whose ear alone was his guide in accompanying a few simple hymns. Mr. Cook went through the regular morning service which has been translated by into Dakota or Sioux tongue by the Rev. Samuel D. Hinman, and small prayer books are given out, though only the interpreter and a few others could read them. The service was decorously conducted, though now and then a dog walked in the open door…” (same date, page 39)

A vacancy shortly thereafter transferred her back to the first stop on her trip, the Ponca Agency, where she had met Mr. Gregory. The trip there was treacherous due to very bad weather. (page 41)

“Lights were visible in the mission house and we were kindly welcomed. The Rev. J. Owen Dorsey and his mother, Mrs. Stanforth, conduct this work…” (May 1, 1872, page 42)

The teaching begins

“Enough to do? Indeed there is. As these poor Poncas have no appropriation from the government for food, no Ration Day, and subsist as best they can from their poor farms and charity. The tribe is a small one, only about 600, and Maj. Gregory is striving to secure better days for them. Oh these poor children whom we are trying to reach to read English and to live in the White man’s way! Seven dirty children were assigned to me today to read from their primers “I see a cat.” And I was cautioned to note that the fourteen small hands were all affected by the itch, that a basin was beside the door and that each child must receive an application of the ointment prepared for that purpose.” (same date, page 44)

A Sioux attack

“The hostile Sioux have frequently been seen on the bluffs back of the Agency, dashing down now and then to steal a Ponca pony and finally by killing and scalping a lone Ponca man, who ventured too far out alone…. All the able bodied men gathered for defense. They were all naked save for breech bloth and hideously painted from head to foot; one demon was his entire self one half green and one half black as ink. Mounted on their fleetest ponies they circled about the mission house and gesticulating wildly and talking incessantly. Their agent did all in his power to quiet them and had their dead comrade decently buried.” Help is called for at a neighboring fort (Ft. Smith) and the women and children are secluded. (June 1, 1872, page 45)

The commotion leads to plans to move the Ponca to live with the Omahas, and Anna is moved back to Yankton.

“Preparations are being made for the removal of the Poncas from their present location to a reservation further South in Nebraska which they may share with the Omahas with whom they are allied.” (June 25, 1872, page 47)

Classes at Yankton start their fall session.

“This coming week will bring the opening of the school, which is held in the front half of the church, outside the chancel of course. I have made a black board to fit on a sort of easel frame so that I may change it about or quickly remove it altogether. The Indians do so well love Music! I regret I neither play nor sing since I could be much more useful….” (September 1, page 51)

The death of Flying Pipe

Through the past size weeks there has lain literally at our gate a sick and dying man whose tepee was set up there that we might the more readily attend to him. Every day one of us has carried him – Flying Pipe – a disk of food and bowl of tea of which every mouthful had to be fed to him. Now the poor tortured body is lifeless and Mr. Cook is to conduct his funeral at sunset, the heat being so great earlier. Immediately the tepee will be removed as no one of the Sioux will ever sleep in a teepee on the spots where a death has occurred. (same date, page 52)

She discusses the work of the mission when handing out rations and to develop farming

“These people have many good farms and are rapidly learning to care for them properly. On the evening before Ration Day, teepees will spring up as though by magic all about the agency and there are pregnant calls from one group to another to share in a dog feast. They raise these pets for boils and stews when the supply of beef runs low. All is bustle and stir on the morning of issue day. The agency stands ready with scales and measures to supply each head of the family with the quantity of flour, bacon, coffee, salt, sugar, and soda or baking powder his ticket calls for…” (same date, page 52)

And Anna notes the home life of the women of the Sioux

“The woman of the family performs the hardest part of the labor of their simply home life; she cuts the wood, tends the fires, carries home the beef on her back and her lord and master carries – his pipe. All the water used by the white families is brought from the Missouri river in a large tank on wheels, drawn by two or four horses as traveling (wheeling) may be, distributing it on regular days, each family keeping one or more large barrels for its reception. The Indians in their distant camps learn to be economical with water, as in most instances it is carried from the river by the woman in a keg which rests on her shoulders and is held in place by a leather strap bound across her forehead….” (same date, pate 53)

Her assistant is later Chief David Tatiyopa

“We have opened school and the bell is run at 845am, my Indian assistant David Tatiyopa being on hand and for two days the attendance was good, that is about 20 present but then a steam boat came and the pupils did not come.” (Sept 5, 1872, page 54)

With Mrs. Gasmann, she has created a sewing school.

“One school is doing fairly well and some days are really quite encouraging. Dear Mrs. Gasmann has helped me organize a sewing school to meet Saturday afternoons in the church and though but six timid women came in response to the first invitation we are convinced the numbers will increase.” (Oct 1 1872, page 55)

Baptism on the reservation

“Upon receiving baptism, the child or adult drops the heath name of ‘Girl walks backwards’ or whatever it may be and received the one of Mary, Lucy or any one the clergymen see fit to bestow upon her.” (Dec, 27, 1872, page 56)

The conversion of Sioux Chief Deloria

“The Sunday services are most interesting. Scarcely one passes without one or more baptisms, some of infants and many of all ages. An old Chief, Deloria, who has been long considering the duty of giving up all save one wife and then of being publicly married to her, at last asked to have the ceremony performed and before a congregation of curious or sympathetic witnesses. The old chief and his wrinkled but smiling old wife responded clearly as directed. One of the sons of the couple, Philip Deloria, is a remarkably fine fellow of about 21 years who already possesses a fair education and is planning to become a minister to his people.” (Feb 16 1872, page 59)

Bishop Hare and the new St. Paul’s school

“Bishop Hare, who has come to take up his perplexing burden, is an elegant and scholarly gentleman… He plans to erect at once a building some 300 feet distant from this one to be known as St. Paul’s school for Indian boys…” (May 15 1873, page 62)

“St. Paul’s school is a reality, Mrs. Duigan bieng house mother and the Rev. Henry St. George Young house master. There is already quite a number of boys gathered there and they are to be taught to do house and garden work as well as handle book and slate. This building is to have a large two story addition running out from the western end of the church and here a boarding school of 20 girls to be established.” (Jan 1, 1874, page 63)

Burials on the reservation

“All Christian Indians desire and receive burial in the cemetery back of the mission grounds but we have just witnessed one of the genuine heathen funerals. A very popular young man, a great dancer, died yesterday and all night long we could hear the wailing crises of his friends as they walked and walked dover the bluffs occasionally cutting small gashes in breast or legs to demonstrate their grief and to give zest to their howls. During this afternoon, the funeral procession passed here, the body wrapped and bound securely in blankets lying on a sort of little borne by friends, while his favorite pony was immediately behind its dead master. Some on horseback and many on foot there followed quite a string of mourners winding their way to a distant high bluff where a sort of scaffold about 6 feet high had been erected. On top of this scaffold the body was laid in its wrappings and secured firmly in place, then the pony was led so as to stand directly underneath his master then and there killed by a host which we distinctly heard. The body of the pony will be left there as it felt and daily some friend will carry a small quantity of food and place it on the scaffold that the spirit of the man may still ride and feast as of old. In the case of death of a Christian Indian the agency carpenter makes a coffin of pine of required dimensions, painting the outside white or black… then follows a solemn service in the church and we all go up to the cemetery so as to afford all possible comfort to the bereft family. Several times I have stood and held an umbrella over Mr. bared head while he officiated at the grave in pelting rain or burning sun.” (May 1, 1874, page 68)

The new addition for the girls is done, with some description devoted to it

“The second floor is one large dormitory with 20 lockers along the sides for the girls use. Mother Lang left us some time ago, as she could take up her more lucrative and congenial work of ladies nurse in Yankton, and Miss Sarah Robbins is house mother. Miss Campbell attends to the cooking, washing, etc…. Our school is nicely started, though not taxed to its full capacity. Miss Robbins and I share one of the new bedrooms and Miss Amelia Ives has the tower room. Miss Ives has exclusive charge at the St. Paul’s School of the large store room Bishop Hare has established there…” (Sept 15, 1874, Page 70)

The next several pages are devoted to her engagement and married to Major Henry Gregory, the birth of their children, and her removal from Yankton to the Lower Brule Agency, or White River, after the appointment there of her husband.

Accusations were made against many of the Indian agents of the period of financial improprieties. Gregory was caught up in this and was for a while removed from his position.

“Both Dr. Livingston and Henry have some enemies among the army officers who have not been able to run these two agencies and such misrepresentations have been made that suddenly, with no warning both agencies have been seized by officers with soldiers ordered to keep both agents away from their books and supplies till investigations shall be made.” (April 3, 1878, page 89)

She recounts being present at the suicide of brother in law John Shaw Gregory.

She meets Red Cloud at the Pine Creek Agency

“Our old friend the Rev. John Robinson, now Merrick, is the missionary here. These Indians, whose Chief Red Cloud is a fine man and quite celebrated, are an industrious tribe, doing a deal of freighting and spending money money freely.”

They head back to CT and see Barnum’s performance featuring the famous Jumbo the Elephant.

“The children had great fun feeding the big elephant Jumbo at Barnum’s.” (march 10 1883, page 106)

Heading back West, they are once again back at Lower Brule Agency.

“Here are now the Rev. Luke Walker, a full blonded Santee Indian with a white wife, is a priest in charge of this mission”

The Brule natives revolted.

“We have passed the worst Indian scare I have ever experienced. Henry was ordered to make a new count (census) of the whole tribe of Brules on this reservation but when the Indians learned of the order they rebelled as they delight in making a larger showing than they really have, thinking thus to obtain more food. Henry appealed to his superior Maj. Gasmann for privilege of telling them they must obey orders and rations would be withheld till they agreed to be counted. They better element, more than half the tribe very sensibly came to terms but there have bene mutterings and threats and several days passed beyond the usual issue day and finally the wild ones rose. They filled the office, pushed Henry out of it and then came down towards the housing carrying him and tossing him though not roughly. A great commotion was all about us, but the Indian policemen stood firmly by Henry and the malcontents were persuaded to keep quiet til Maj. Gasmann could come down to talk with them further…” (Aug 1885, page 111)

At this point, the diary deals primarily with personal issues, including Henry’s death, at which point, in the early 1900s, it jumps to the 1920s and then quickly into the 30s. She is back east with her children. Her son Harry, such a major presence in the book, passes away, leaving her to finish the book in her 80s and 90s with a handful of entries noting the Depression.

Pages 143-168 consist of a detailed biography of Henry E. Gregory by his wife. So the first section of the book is her family’s biography. The second is her biography of her husband. Both as bookends.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services