Emily Dickinson on Her Revered Father: He “was always so gallant to his young kinsmen”, and was capable of “great tenderness”

An unpublished three-page letter to her Uncle William, with extremely rare characterizations of her father, whose towering figure dominated her early life.

A long, 3-page letter filled with references to seven members of her family, including her mother; On her cousin, she lyrically writes: “Though not knowing her personally, we have a vicarious acquaintance”; An exceedingly are ALS

Emily Dickinson grew up in a prominent and prosperous household in Amherst, Massachusetts. Along with her...

A long, 3-page letter filled with references to seven members of her family, including her mother; On her cousin, she lyrically writes: “Though not knowing her personally, we have a vicarious acquaintance”; An exceedingly are ALS

Emily Dickinson grew up in a prominent and prosperous household in Amherst, Massachusetts. Along with her younger sister Lavinia and older brother Austin, she experienced a quiet and reserved family life headed by her father Edward Dickinson. In a letter to Austin at law school, Emily once described the atmosphere in her father's house as "pretty much all sobriety." Edward attempted to direct her and protect her from reading books that might "joggle" her mind, particularly her religious faith, but her individualistic instincts and irreverent sensibilities created conflicts that did not allow her to fall into step with the conventional piety, domesticity, and social duty prescribed by her father. In fact, Emily’s independent streak evidenced itself in her writing for the rest of her life.

Emily said of her father, “His Heart was pure and terrible and I think no other like it exists.” Edward embodied the ethics of responsibility, fairness, and personal restraint to a point that contemporaries found his demeanor severe and unyielding. He took his role as head of his family seriously, and within his home his decisions and his word were law. He for over forty-five years led a disciplined, civic-minded public life that included several times representing Amherst in the state legislature, serving thirty-seven years as treasurer of Amherst College, and being elected to the Thirty-third Congress from his region. He was a prominent citizen, active in several reform societies, on the board of regional institutions, and involved in major civic improvements, such as leading the effort to bring the railroad to town in the mid 1850s. Ever respectful of her father's nature ("the straightest engine" that "never played", Dickinson obeyed him as a child, but found ways to rebel or circumvent him as a young woman, and finally, with wit and occasional exasperation, learned to accommodate with his autocratic ways. Her early resistance slowly shifted to a mutual respect, and finally subsided after his death in pathos, love, and awe. Despite his public involvements, the poet viewed her father as an isolated, solitary figure, "the oldest and the oddest sort of foreigner," she told a friend, a man who read "lonely & rigorous books", yet who made sure the birds were fed in winter. When he died, she said, "Lay this Laurel on the one Too intrinsic for Renown Laurel vail your deathless tree Him you chasten – that is he.”

Her father’s brother William, an industrialist in nearby Worcester, was close to the family, and Emily saw him on visits exchanged to each other’s homes. William was the object of her attempt – at age 13 -to get a piano, as she asked for his intercession in finding one. The next year one was delivered to her home. She played it and sang to her father, much to his delight. William’s second wife was Mary, and their daughter – Emily’s cousin – was Helen. Helen married Thomas L. Shields in Worcester on October 26, 1880. Despite her affection for her Uncle, Emily did not leave home to attend the wedding; afterwards he sent her mementos.

Other family members mentioned in this letter are Aunt Libbie (who was Uncle William's and her father Edward's youngest sister Elizabeth Dickinson Currier), who kept house for her brother William in Worcester after his first wife died in 1851. Clara was her cousin Clara Newman, whose mother Mary was also a sister of William and Edward. Emily's father Edward had died in 1874. In 1875, her mother, Emily Norcross Dickinson, suffered a temporarily paralyzing stroke; three years later, she fell and broke her hip. Emily and her sister, Lavinia ("Vinnie") cared for their invalid mother until her death on November 14, 1882.

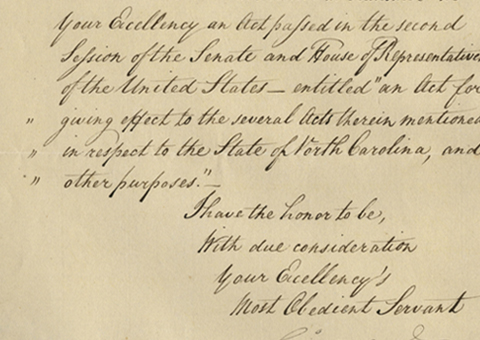

Autograph letter signed, three pages, in pencil, Amherst, no date but November 1880, to Uncle William, thanking him for Helen's cards in the wake of her wedding, filled with mentions of Emily’s relatives, and containing two characterizations of her father. "Thank you, dear Uncle for Helen's cards – You were very thoughtful to send them – though not knowing her personally, we have a vicarious acquaintance through Aunt Libbie and Clara. I hope she may have a charming home, and that Aunt Mary and you may not be too lonely. Please enclose our congratulations when you write my cousin, she will perhaps prize for her Uncle's sake, who was always so gallant to his young kinsmen – and who thought of your home as of his own, and of you – with so great tenderness – Please say to Aunt Mary that we do not forget her. I hope you are both most happy and well – Mother and Vinnie give their love – That we warmly remember Papa's Brother, he will please be sure. Will he guess that the note is from Emily." The paper has an 1876 watermark, and is not published in “The Letters of Emily Dickinson”, edited by Dr. Thomas Johnson. We knew Dr. Johnson personally, and just wish we could go to his office and present him with this unpublished Dickinson letter.

Henry Hills was a close friend of Austin Dickinson, and his wife was a correspondent of Emily’s. This letter, along with a few dozen others of Emily, came into the possession of the Hill family, and remained with them until the 1960s. At that time they were sold to the much-missed Goodspeed’s Bookshop in Boston. Many of the pieces were acquired at that time by the C. Waller Barrett Library, and the remaining ones went to collectors. This particular letter is one of the latter, and was last offered for sale over three decades ago.

A search of public sale records going back to the mid-1970s reveals that fewer than a dozen ALSs of Emily Dickinson have reached that market during all that time. This is the first we call recall seeing in the private market containing characterizations of her father.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services