Sold – Signer William Williams Makes a Patriot’s Argument to a Loyalist

He anticipates Nathan Hale: “[I] should not fear to stake ten thousand lives if I had them, that it would end in establishing our liberties”.

In 1774, the British government imposed the Intolerable Acts which annulled the Massachusetts charter, took control of local government from the hands of the colonists and closed the port of Boston. All colonies saw this as a threat to their own independence, and in response, from September 5 to October 26, 1774...

In 1774, the British government imposed the Intolerable Acts which annulled the Massachusetts charter, took control of local government from the hands of the colonists and closed the port of Boston. All colonies saw this as a threat to their own independence, and in response, from September 5 to October 26, 1774 , the First Continental Congress met in Philadelphia with 56 delegates, representing every colony except Georgia.

Attendants included Patrick Henry, George Washington, Samuel Adams and John Hancock. On October 14, a Declaration and Resolves were adopted that both opposed the Intolerable Acts and other measure taken by the British that undermined colonial self-rule, and promoted the formation of local militia units for defence. The rights of the colonists were asserted, including those to "life, liberty and property." On October 20, the Congress adopted the Continental Association in which delegates agreed to a boycott of British imports and an embargo of exports. These measures failing to effect an alteration in the British position, on February 1, 1775, the Massachusetts provincial congress met during which John Hancock and Joseph Warren began defensive preparations for a state of war. Eight days later, the British Parliament declared Massachusetts to be in a state of rebellion. News of that measure reached American shores in mid-March 1775. By then the time for effecting a compromise had passed, Americans were taking sides, and the war was just one month away.

In 1756, after serving in the French and Indian War, William Williams became town clerk of Lebanon, Connecticut, a post he would retain for 45 years. However, he was also active on the state and national levels. In 1757, he was selected as a representative to the Connecticut Assembly, rising to hold the office of Speaker in the momentous year of 1775, when the American Revolution commenced and citizens took sides. The following year, with the question of independence under debate and Williams being a known advocate, he was elected to serve as a Connecticut delegate to the Continental Congress. Williams arrived too late to vote for the Declaration of Independence on July 2, 1776. He was, however, on hand on August 4, when he joined with the other delegates in signing the official, engrossed Declaration. He continued to serve as a member of the Continental Congress through 1777. A man of ardent temper, Williams threw himself vehemently into the struggle for independence, wielding a vigorous pen and drawing generously on his purse in support of military activities. During a great part of the Revolutionary War he was a member of the Council of Safety, and expended nearly all his property in the patriot cause. He even went from house to house soliciting donations to supply the army.

Benjamin Stiles, a 1740 graduate of Yale College, was a noted Connecticut lawyer who represented Southbury in the Connecticut Assembly from 1754–71. He was a conservative and on the approach of the American Revolution took the part of a Tory. In October 1775, it was charged that he had “publickly and contemptuously uttered and spoken many things against the qualification of the three delegates of the colony now belonging to the Continental Congress, &c., &c., whereof he hath openly showed his inimical temper of mind and unfriendly disposition." He was cited to appear before the General Assembly. Col. Benjamin Hinman, mentioned in this letter, was a Lieut. Colonel in the French and Indian War and commanded the Connecticut Militia. On the outbreak of the Revolution, he was appointed colonel of one of the Connecticut regiments and served with distinction during the war. The Governor spoken of was Jonathan Trumbull, a patriot who supported American independence and was the only colonial governor to continue in office through the Revolution. He also happened to be Williams’ father-in-law.

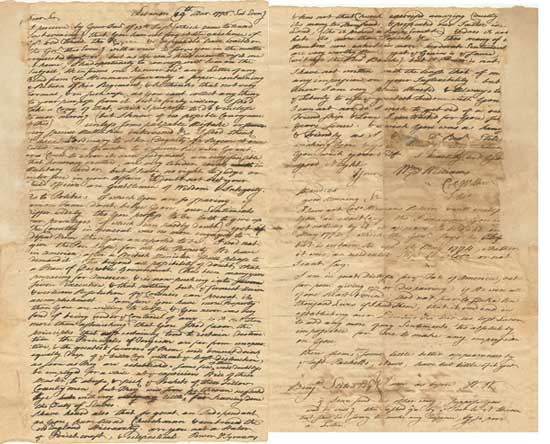

Autograph Letter Signed, Lebanon, Conn., Saturday evening, March 19, 1775, to Benjamin Stiles. Missing margins have resulted in the loss of some letters and a few words, though fortunately virtually all of the lost text is easily reconstructed. “I perceive by your last of 13th instant (which came to hand last evening) that you have not forgot the existence of your old friend, though etc…[I] designed to have waited on the Governor this evening with a view to serve you in the matter requested by you, but as he was kind enough to visit me at home, I had opportunity to converse with him on the subject. He informs me he never received any letter of any kind from Colonel Hinman save only a paper containing a return of his Regiment, & he thinks that not very formal, & in such wise as you can’t collect anything to your purpose from it, but is freely willing I should take a copy of that, which I propose to do & inclose tomorrow morning (but I know of no possible conveyance of this). Unless some palpable mistake or very special matter has intervened etc., I should think it as extraordinary to alter dignity of a regiment once settled as for a grantor to assume his own grant and Court to error its own judgment. [I] am very sensible that honorary matters are very tender points in military order but I have no right to judge or interfere in your affairs & doubt not but that your field officers are gentlemen of wisdom & integrity.

As to politics, of which you are so sparing, if common fame do not belie you, our sentiments differ widely. Though you profess to be loath to give up your privileges (of which I can hardly doubt), yet if the Country in general was no more engaged to defend them than you are reported to be, I would not give the pen I use for all the property we have in America, after a British minister shall please to demand it. Tis beyond all possibility of doubt that a plan of despotic government has been many years preparing for America, and is now pushing into severe execution, & that nothing but the firmest union & virtuous resolution of the Colonies can prevent its accomplishment. I am sure that you have more property than you are willing to lose, & you never was very fond of being under the control of any, is it not then more than astonishing? that you should favor the principles that most certainly tend to certain destruction. The principles of Toryism are far from unoperative & the greatest favorers of them will & must drink equally deep of ye bitter cup without the least distinction as soon as they are established. Some few of them will doubtless be employed for a while at ye capricious will of their master, to abuse and pick ye pockets of their fellow Countrymen, but they will soon be thrown neglected bye, with very little thanks for having done the duty of slaves.

I have heard also that so great an independent as you have turned churchman & embraced the old England hiarchy. Are you not a hater of priest enough, & ecclesiastical power & tyranny, & has not that church exercised amazing cruelty [to] its many ten thousands, & persecuted our Fathers in [Eng] land, though it proved a happy event etc. & does it not hate us more than Papists etc. though many of [its] members now entertain more moderate sentiments [and] are very worthy men. Yet ye genius is the same (witness the Rev. ?), but the power is not. I have not written with the least thought of [making] any impression on your inflexibility, but [you] know I am very plain hearted & always [take] ye liberty to use ye greatest freedom with you. I cannot nor do I wish to get rid of an old friendship & love…I wish you was as… friendly as I…I heartily bid you good night.” He continues the letter on Monday morning the 20th, quite possibly after hearing word that the British Parliament had declared Massachusetts to be in a state of rebellion. “I have got Colonel Hinman’s return & will inclose you an exact copy, though I imagine you [will] get nothing by it. It appears to be dated [in] May 1772, which the Governor says…but is certain he received it May 1774, whether it was an accidental slip by ye Colonel or not I can’t say.

I am in great distress for ye fate of America, & far from giving up or despairing, if we were all of one heart & mind, [I] should not fear to stake ten thousand lives if I had them, that it would end in establishing our liberties etc. But tis lost labor to add any more of my sentiments, tis absolutely for me to make any impression on you. There seems now some little better appearances by the last packets…” He signs with initials, then continues “If I can find no other way, [I] suppose you would be willing I then should [send] by post to New Haven, but [I] should be sorry to make any expense by so poor a letter.” Although Williams ironically expresses concern about this being “so poor a letter,” in fact it is nothing short of extraordinary. We do not recall seeing, nor can we find record of, another signer’s letter in the marketplace so eloquently putting into words the essential argument, both political and personal, in America at the dawn of the Revolution – Patriot versus Loyalist.

Just 25 days after writing this letter, Massachusetts Royal Governor Gage was secretly ordered by the British government to enforce the Intolerable Acts and suppress "open rebellion" among colonists by using all necessary force. On April 18, 1775, he ordered 700 British soldiers to Concord to destroy the colonists’ weapons depot. That night, Paul Revere and William Dawes were sent from Boston to warn the colonists. Revere reached Lexington about midnight and warned Samuel Adams and John Hancock who were hiding out there. At dawn on April 19, about 70 armed Massachusetts militiamen stood face to face on Lexington Green with the British advance guard. At that moment, the ‘shot heard around the world’ began the American Revolution.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services