Andrew Jackson’s Original “Trail of Tears” Letter

The Historic Instructions that Initiated the Government's Removal Policy, written to the “Civilized” Indian Tribes to Remove Themselves from the American South and Move West

For years this was on display in the permanent exhibition at the National Constitution Center. They wrote: “This letter signed by President Andrew Jackson just seven months after he took office initiated the government’s policy of removing Indian tribes from their native lands in the Southeast in order to make way for...

For years this was on display in the permanent exhibition at the National Constitution Center. They wrote: “This letter signed by President Andrew Jackson just seven months after he took office initiated the government’s policy of removing Indian tribes from their native lands in the Southeast in order to make way for white settlement”

This very letter was read in person to their chiefs, with Jackson’s cajoling and threatening language

Just months later, after the Indians refused, came the Indian Removal Act

As for the new land, the Indians were promised that “they & their children can live upon [it as] long as grass grows or water runs, in peace and plenty. It shall be theirs forever.”

Nothing has more poignantly defined American colonization and dominion than relations with the native tribes. The way in which these two civilizations first contacted each other, dealt with each other, and lived on shared land is a central element of our national identity. In 1829, issues with the Indians and American desire for more territory, burst forth onto the national agenda, and defining American actions would be President Andrew Jackson, which actions would, for more than a century, define not only American relations with the native tribes but westward expansion – an expansion that was the essence of America. This letter, previously lost, represents the initiation of a new and determined policy with broad ramifications, one designed to remove the Indians and establish a precedent for dealing with other Indian tribes in the future.

Up until the early 19th century, the principle was recognized that the Indians were sovereign on their lands, and that treaties were necessary to divest them of their holdings. Although Congress came to take the position that Indians were subject to federal law, the practice of treaty-signings and a spirit of joint occupation of the territory imbued relations between the United States and the Indians tribes in those years.

From time immemorial, five Native American tribes in the South – the Chickasaw, Choctaw, Cherokee, Seminole and Creek – occupied a great domain from which portions of the states of Florida, Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi would be formed. These together are often referred to as the Five Civilized Tribes. As the 19th century began, white settlers began to move into their lands, and seeing the Indians as an impediment, petitioned the government for their removal. In Washington and in state capitals, Indians were increasingly viewed as the main obstacle to westward expansion. States and territories in which the Five Civilized Tribes lived established policies that the people of a state or territory were sovereigns within that jurisdiction’s lands, and that Indians were simply residents of that state or territory like any citizen, without ownership rights as the original inhabitants of the state or territory. Voices began being heard seeking removal of the Indians. However, without active cooperation from Washington, these did not result in Indian removal. An 1802 federal law provided for the relocation of the tribes in Georgia to the new Louisiana Purchase as soon as could be amicably accomplished. Still no tangible action was taken to implement the law.

Andrew Jackson occupies a unique role in the history of this clash of civilizations. In 1814, Major General Jackson led an expedition against the Creek Indians climaxing in the Battle of Horse Shoe Bend (in present day Alabama near the Georgia border), where Jackson’s force soundly defeated the Creeks and destroyed their military power. He then forced upon the Indians a treaty whereby they surrendered to the United States over twenty-million acres of their traditional land, about one-half of present day Alabama and one-fifth of Georgia. His next salvo was the 1820 Treaty of Doak’s Stand, also known as Treaty with the Choctaw. Jackson was sent as commissioner to conclude the treaty; this reflected the official perception at that time that the Indians’ concurrence by treaty was a necessity. The convention began on October 10 with a talk by “Sharp Knife,” the nickname given to Jackson, to more than 500 Choctaws. Chief Pushmataha accused Jackson of deceiving them about the quality of land west of the Mississippi. Jackson reportedly shouted “If you refuse … the nation will be destroyed.” On October 18 the treaty was signed. The Choctaw agreed to give up approximately one-half of their homeland.

As the 1820’s developed, Jackson publicly took the position that these Native Americans were simply residents of a jurisdiction like anyone else. This translated well into his brand of popular democracy, which placed power and sovereignty in the hands of the people of a state or territory. He rode to victory in the 1828 Presidential election and was inaugurated on March 4, 1829. According to the Jackson Papers, he had two pressing concerns on taking office.

The second was dealing with cabinet issues (the Peggy Eaton affair). However, first and foremost was adopting an Indian policy, as Indian issues were a boiling fire. Between the time Jackson was elected and his inauguration, the states of Georgia, Alabama and Mississippi passed laws making tribes subjects to state dominion. But enforcement was an issue and local efforts to cajole tribes to move West hit a wall. Politicians bemoaned the contrast between the stated policy of removal and the laxity with which it was pursued. After he entered the White House, the clamor among Jackson’s core constituency for removal had risen to a high pitch. In his first address to Congress, the President supported this goal. In September 1829, he began iterating his policy in an organized way to these constituents, with his stated intention to remove the tribes. He circulated copies of his position to white supporters.

In October, Jackson received a letter from an influential Mississippi military man and mail contractor, Major David Haley. Haley, well known in the Choctaw nation, wrote that only action by Jackson himself would convince the Indians to move West. “The chiefs cannot prepare the Indians for a treaty. This must be done by the government through some person that the Indians are well acquainted with who has influence with them. This person must go through the nation and call the indians in council in the different towns and reason with them…This power must come directly from you.” Haley volunteered to do just this. He also included letters from others attesting to Choctaw unwillingness to submit to local law. They warned that any chief that dared advocate removal would be endangering his life. We know that Jackson met personally in the White House with Haley for two reasons. First, he has docketed Haley’s letter with the words, “Major Haley to be seen and conversed with on the within subject.” The second reason is this letter, newly discovered.

Jackson believed in the principle that leadership would come from him, and that the national government must take active leadership in forcing the issue. He accepted Haley’s offer, thus taking the first step in not only his active involvement but in dealing with the Indian problem decisively and ending it on a national basis.

The President dictated a letter he handed to Haley, and it was taken by Haley himself to the seats of power in the Choctaw and Chickasaw nations, which were where this first confrontation would take place. The letter was to be read aloud by Haley to the Indians, who was to assure them of its authenticity. It was carried by Haley throughout the southeastern stretches of the U.S. and was read to hundreds of Native Americans and their leaders. The original of this letter was lost to time, though from a draft it became famous and is quoted in countless books on the subject, such as Fathers and Children: Andrew Jackson and the Subjugation of the American Indian by Michael Paul Rogin. Until now, the real content of the letter Jackson gave Haley has been unknown. Some small amount of text has been lost, but this is the Letter Signed, likely in the hand of his nephew Andrew Jackson Donelson, Washington City, October 15, 1829, to Haley, presented and not mailed, and carried throughout the Choctaw and Chickasaw nations.

“Having kindly offered to be the bearer of any communications to the Indians [through the] countries you will pass on your [way] home, which I might think proper to make to [them, I], take the liberty of placing in your hands [copies] of a talk made by me last Spring, to the [Creeks] which I wish you to show to the Chiefs of the…Choctaws. As far as this talk relates to the present situation and future prospects, it is their white brothers and my wishes for them to remove beyond the Mississippi, it [contains] the [best] advice to both the Choctaws and Chickasaws, whose happiness and…will certainly be promoted by removing [beyond] the Mississippi.

“Say to them as friends and brothers to listen [to] the voice of their father, & friend. Where [they] now are, they and my white children are too near each other to live in harmony & peace. Their game is destroyed and many of their people will not work & till the earth. Beyond the great river Mississippi, where a part of their nation has gone, their father has provided a co[untry] large enough for them all, and he ad[vises] them to go to it. There, their white…[will not trou]ble them, they will have no claim to [the l]and, and they & their children can live upon [it as] long as grass grows or water runs, in peace and plenty. It shall be theirs forever. For the improvements which they have made in the country where they now live, and for the stock which they [can]not take with them, their father will [sti]pulate, in a treaty to be held with them, [to] pay them a fair price.

“Say to my red Choctaw children, and my Chickasaw children to listen. My white children of Mississippi have extended their laws over their country; and if they remain where they now are…must be subject to those laws. If they will [remove] across the Mississippi, they will be free [from] those laws, and subject only to their own, and the care of their father the President. Where they now are, say to them, their father the President cannot prevent the operation of the laws of Mississippi. They are within the limits of that state, and I pray you to explain to them, that so far from the United States having a right to question the authority of any State to regulate its affairs within its own limits, they will be obliged to sustain the exercise of this right. Say to the chiefs & warriors that I am their friend, that I wish to act as their friend, but they must, by removing from the limits of the States of Mississippi and Alabama, and by being settled on the lands I offer them, put it in my power to be such.

“That the chiefs and warriors may fully understand this talk, you will please [go] among them and explain it; and tell [them] it is from my own mouth you have it and that I never speak with a [forked] tongue.” Here a portion of a page is unclear. However, using the text of the draft and extant final segments, it continues:

“Whenever [they make up their] minds to exchange [their lands]…[for land] west of the river Mississippi, [that I will direct] a treaty to be held with them, [and assure them, that every] thing just & liberal shall [be extended to them in that treaty.] Their improvements [will be paid for], stock if left will be paid [for, and all who] wish to remain as citizens [shall have] reservations laid out to cover [their improv]ements; and the justice due [from a] father to his red children will [be awarded to] them. [Again I] beg you, tell them to listen. [The plan proposed] is the only one by which [they can be] perpetuated as a nation….the only one by which they can expect to preserve their own laws, & be benefitted by the care and humane attention of the United States. I am very respectfully your friend, & the friend of my Choctaw and Chickasaw brethren. Andrew Jackson.”

Jackson’s changes are subtly interesting. In the published version, paragraph one, Jackson told the Indians that they must remove if they wanted to “preserve their Nation.” This threatening language was removed in the final. In paragraph two he added that he was the Indians’ “father &?friend.” In paragraph three, he adds that if the Indians “remain where they now are [they] must be subject to those [state] laws.” In the last paragraph, he underlines “Tell them to listen” and adds that only by listening can they “be benefitted by the care and humane attention of the United States.” So he is both shaving away some overtly threatening language while thrice insisting rather threateningly that the Indians listen, and also adding some points he saw as useful to his presentation.

This letter shows Jackson’s apparent view of the limitations on Presidential power under the Constitution. It also gives a glimpse of how the Constitution was maneuvered around to ignore its treaty-making provisions, and to unilaterally claim for states powers of supremacy over the federal government they did not have. It also is an irony that just four years later, this same President Jackson was denying that state laws could nullify federal power in his altercation with South Carolina.

On November 29, the message reached Choctaw Chief David Folsom. On December 14, the Missionary Herald reports that the Chief rejected removal. Folsom had fought side by side with Jackson years earlier and was the son of a white man and himself a Christian. The stage was set for a confrontation the Indians could not win.

In May 1830, in direct response to this rejection, Jackson promoted through Congress and signed into law the Indian Removal Act, allowing him to implement his goals under U.S. law. Then commenced the Trail of Tears. In 1831, the Choctaw were the first to be removed, and they became the model for all other removals. After the Choctaw, the Seminole were removed in 1832, the Creek in 1834, then the Chickasaw in 1837, and finally the Cherokee in 1838.

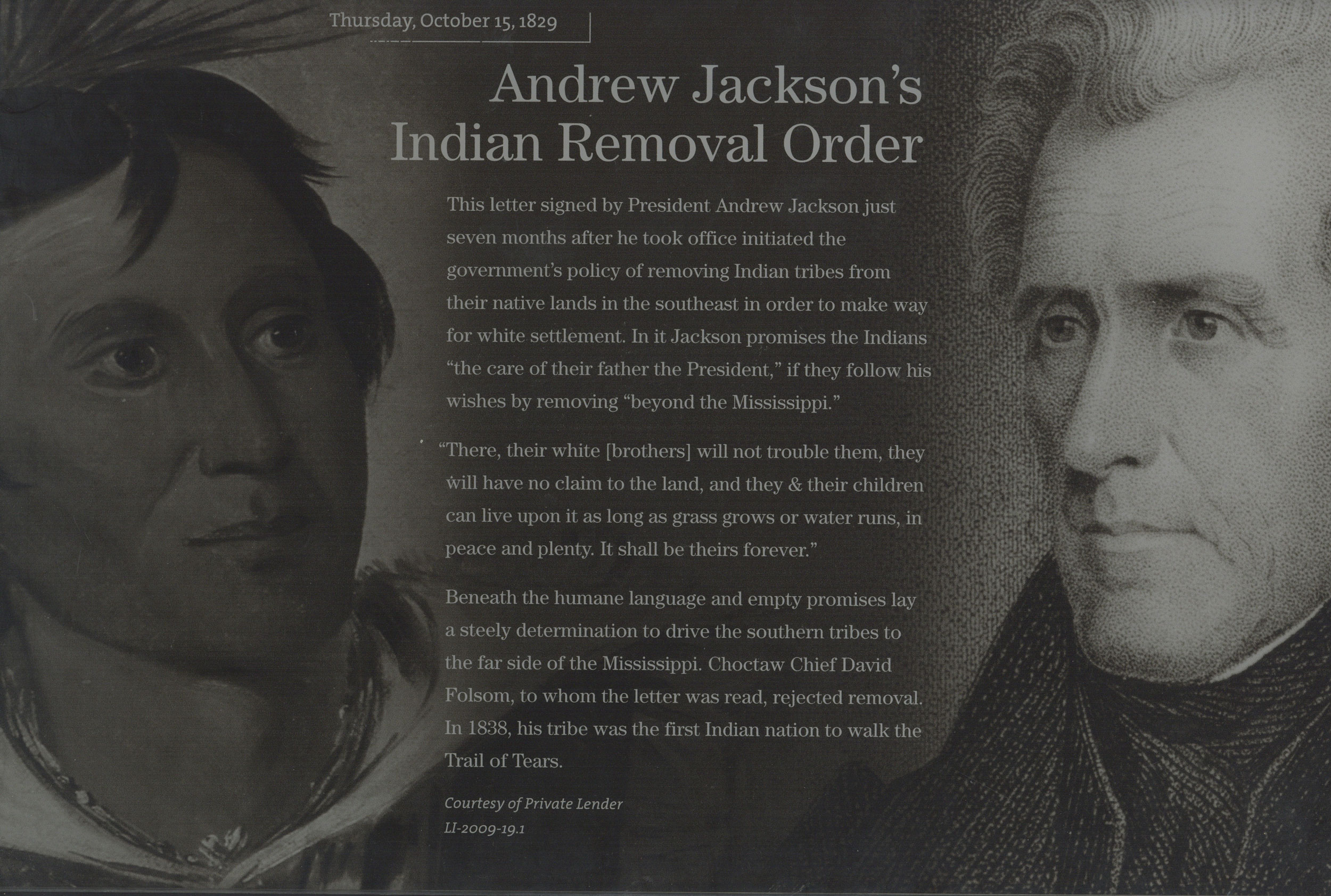

This letter was for years displayed as part of the permanent exhibition at the National Constitution Center. The plaque that stood next to the letter on display comes with the letter. It reads: “This letter signed by President Andrew Jackson just seven months after he took office initiated the government’s policy of removing Indian tribes from their native lands in the Southeast in order to make way for white settlement. In it Jackson promises the Indians ‘the care of their father the President” if they follow his wishes by “removing beyond the Mississippi.” “There, their white [brothers] will not trouble them, they will have no claim to the land, and they & their children can live upon it as long as grass grows or water runs, in peace and plenty. It shall be theirs forever.’

Beneath the humane language and empty promises lay a steely determination to drive the southern tribes to the far side of the Mississippi. Choctaw Chief David Folsom, to whom the letter was read, rejected removal. In 1838, his tribe was the first Indian nation to walk the Trail of Tears.”

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services