The Slave Trade, Secret Alliances, and a New World Order: The First Major US Diplomat to South America, In Brazil, Issues a Series of Reports to the Americans Negotiating in Europe in 1814, Warning of a New Potential Alliance in the Western Hemisphere

A remarkable and archive, with much unpublished material, relating to the Argentine War of Independence, the balance of power in South America, the slave trade, neutrality, and issues that emerged with the fall of Napoleon and transatlantic peace.

“England is probably waiting only until they decree the abolition of the Slave trade at Vienna, to force that measure upon Spain and Portugal, which will throw all these countries into confusion”

For the first two centuries of the Spanish empire in America, the vast region draining from the Andes Mountains east...

“England is probably waiting only until they decree the abolition of the Slave trade at Vienna, to force that measure upon Spain and Portugal, which will throw all these countries into confusion”

For the first two centuries of the Spanish empire in America, the vast region draining from the Andes Mountains east to the River Plate at Buenos Aires had no direct link with Spain, all official contact being through the Viceroy in Lima. In 1726 Buenos Aires had a population of only 2200. In 1776 the entire area, from the eastern Bolivian highlands through Paraguay, Uruguay and Argentina to the southern tip of the continent, was given separate status as the viceroyalty of La Plata with its capital at Buenos Aires.

The Napoleonic conflicts had a major impact on the colonies in South America, both Spanish and Portuguese. The Portuguese royal family fled their country to temporarily reside in Brazil and its capital, Rio de Janeiro. There they forged an alliance with Great Britain, which was fighting their enemy and usurper, the French. In Spain, King Ferdinand VII was replaced by Napoleon with his brother Jerome, a deeply unpopular move in Spain.

In 1810, the Argentine War of Independence began, a war that would last eight years. It pitted the Argentine patriotic forces, headed by Generals Belgrano and General San Martin, against forces loyal to the Spanish crown. The patriots, who fought nominally in the name of the deposed Ferdinand VII, established a new governing region called the United Provinces of the Rio de la Plata. In mid-1814, patriot forces clinched an important naval victory over the Spanish, securing Buenos Aires and dooming Spanish rule in Uruguay.

In March 1814, following Napoleon’s defeat and the collapse of the First French Empire, Ferdinand VII was restored to the Spanish throne. This signified an important change, since most of the political and legal changes made on both sides of the Atlantic—the myriad of juntas, the Cortes in Spain and several of the congresses in the Americas, and many of the constitutions and new legal codes—had been made in his name. Before entering Spanish territory, Ferdinand made loose promises to the Cortes that he would uphold the Spanish Constitution. But once in Spain he realized that he had significant support from conservatives in the general population and the hierarchy of the Spanish Catholic Church; so, on May 4, he repudiated the Constitution and ordered the arrest of liberal leaders on May 10. Meanwhile, the patriots in Argentina wished to go to the court of Spain and meet with Ferdinand VII to gain an alliance or a recognition of their efforts, yet they had no direct conduit.

As all this was happening in South America, the peace in Europe shook up the status quo. Napoleon was overthrown (if only temporarily), and negotiators in Ghent had ended the War of 1812. This freed Britain from the drag of ongoing wars, which opened up a host of new issues for the Western Hemisphere. The Spanish and Portuguese colonial powers had been enemies of the French and by virtue of that not enemies of Britain. The Portuguese court in fact was in effect allies of the British. Would the end of war mean a new commercial or colonial dominance by the British on the doorstep of the United States?

The first major US diplomat in all of Latin American was Thomas Sumter, Jr., who was sent to the the Portuguese court in exile in Brazil to negotiate a commercial and political arrangement. He was first hand witness to these epochal events in South America. This he attempted to do.

Although aiming to keep a measured neutrality, he was drawn in to the complicated diplomatic play between the Spanish New and Old Worlds. After the news of the successful negotiations at Ghent reached there, General Belgrano and the Argentines sought an avenue to negotiate in Europe with Ferdinand. They went to Sumter, hoping for an introduction and some influence. This he provided, sending the Argentine leaders over with a letter of introduction, first to London where negotiations for a commercial treaty were taking place, and, failing that, to Crawford as representative in France. Sumter also included a detailed diplomatic assessment of the post-War of 1812 situation in his region, addressed to the American envoys in Britain and France, which the Argentines were to deliver for him. There was a variety of other relevant documents, so the envoys negotiating the commercial treaty would be fully informed on the situation. That same year he also wrote separately to Crawford on the same subject, letters that post-date when the Argentines left Rio.

Sumter was anxious to let the Americans in Europe know the state of hostilities and alliances in South America. Though the South Americans seemed on the verge of securing independence, and the Americans had reinforced theirs in the now-concluded War of 1812, he feared the new peace in Europe would give Britain an opportunity it did not previously have: to spend its efforts full time on the development of a maritime commercial structure where it could dictate the terms of commerce among all parties in the Western Hemisphere. Thus the British, having failed to gain supremacy in the Western Hemisphere by military means, might gain it by commercial ones.

This is a remarkable, and in many cases unpublished, archive of materials. The recipient was the U.S. Ambassador to France, William H. Crawford. Crawford was U.S. ambassador to France during the War of 1812, and was responsible for superintending the American consuls in Europe, and keeping them informed of developments. More than that, he was an advisor to the President on the happenings on the Continent. As Ambassador to the Court of one of the two major adversaries in the conflicts in Europe, he was also actively involved in the Ghent negotiation process, advising the negotiators and responding to their confidential communiqués. He would later serve as Secretary of War and Secretary of the Treasury under Presidents Madison and Monroe.

This archive includes 9 items.

Sumter’s detailed diplomatic report on the region, the Spanish and Portuguese powers, and the impact of the new balance of powers, as it pertains to US interests.

Letter signed, 17 long pages, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, to Crawford, March 10, 1815. In very small part: “It seemed by no means impossible too that Spain and Portugal, who had taken steps to make all America accessible to general commerce, might be forced to acquiesce in this scheme of a general confederacy of the maritime & colonizing powers against the prosperity of the other powers, from the danger of being separated from their American & other foreign possessions, if they should venture to oppose England's views as to the abolition of the Slave trade, or of reestablishing the colonial system in their great continental dominions of America; both of which measures are necessary to the interest and security of her small colonies, and those of the above powers who have been designated as likely to become her confederates, almost all of whom have already abolished the Slave trade or promised to do so in a short time; for were these immense possessions of Spain & Portugal to become permanently open, to the commerce of Europe & America, with the Slave trade existing exclusively in their favor, they would soon sap the colonial system by confining each metropole to the consumption of her own colonial products, and could soon, if it were an object, destroy their existence as colonies, from the mutual benefit the free States in America and the great States without colonies in Europe would derive from their direct intercourse, which would in proportion to their several faculties and intelligence augment their navigation their agriculture, manufactures and maritime strength — It must be confessed that this sort of policy was in June last attributed to England & to the other maritime states rather upon calculation than upon any distinct proofs or indications of her views or theirs.

“It was observable that she had however done much to attach Sweden to her, and to secure Holland, very much – Sicily and Naples too as nations of a different maritime description were either chained or won to her side — Of Portugal she seemed sure and from her footing in the Spanish colonies, gained since the Spanish revolution, she might have hoped to coerce Spain to serve her purposes — as to the abolition of the Slave trade, and as to the modification of the trade to Spanish America, provided the constitution of the Cortes had remained in force, so as not to let it interfere too much with the colonial products of the confederacy and their markets.

"The two difficulties at that time the most prominent in the way of England appeared to be the indisposition of the Prince Regent of Portugal to abolish the Slave trade and to restore the colonial system here: or rather his indisposition, temporary or permanent to return to Lisbon; which fortified his repugnance to be pressed or hurried on the other two points the prospect then existing that the Spanish colonies, tired of their divisions and fruitless efforts for independence separate from Spain, would have yielded to the consolidation enacted in the constitution of the Cortes, under some modification or other, which would have left their commerce acessible in some liberal shape to other powers and particularly to those of Europe which having no colonies would find themselves interested to influence and protect Spain, and also Portugal, in adopting and persisting in their new anticolonial policy, by comprehending America and its commerce in the system of balance to be projected out of the new state of things.

"It seemed at the same time possible by a proper understanding and guarantee of these interests between the great inland powers of Europe and Spain, Portugal and the United States, the joint possessors of all continental America which produce articles wanted by the former, and nothing in rivalship, with them, to raise such a map of influence against England & her colonial system, whatever it might be, as would have detached France, Holland, Sweden and Denmark from her policy in this respect, particularly as what they were likely to recover in their colonies would be too much exposed for them in their present weak state to promise any great or lasting advantage, unless their possession & protection should be provided for in some general scheme of defence armed or unarmed against the commercial and maritime preponderance of England — The choice for them to make would lie between, security for their colonies with a limited but lasting enjoyment of them, in peace with the continents of Europe & America, united to restrain England to peace and the natural profits of her own colonies and foreign possessions – Or, alliance with & dependence upon England, with the prospect of being dragged into all her differences and Wars commercial or political with the north of Europe and with the continental powers of America – Such a state of things would perhaps extinguish the colonial system which has so long disturbed Europe, and place commerce on a better footing than it ever has been…

“It is therefore probable that the intractibility of Ferdinand on the subjects of abolition & colonies to suit the views of the English ministry, will force it to revert to the antient policy, still popular in England, of seizing what she can secure in Spanish America, & protecting, at a certain price in Commercial advantages, the freedom of what she cannot appropriate. Now let this spoil appertain to England alone, or to a confederacy of maritime powers in Europe, the effects thereof must be injurious to all the excluded powers in Europe & to the United States— It is almost certain also, that the destiny of Brazil must assimilate with that of Spanish America — Such views as these I have heretofore thought worthy of the consideration of the United States and of all the powers of Continental Europe, but especially of those who having no colonies must be directly interested in the open Commerce of all America.

“…England is probably waiting only until they decree the abolition of the Slave trade at Vienna, to force that measure upon Spain and Portugal, which will throw all these countries into confusion – Her ministers must anticipate this effect, and probably desire it, rather than see South America free, unless it be connected with or dependent upon England in such a way as to secure the existence & the superior profits of her own colonies; in the former state of colonies they did but little injury to hers, and while they gilded Spain & Portugal they really enriched England & Holland — from experience they have learned not to fear colonies regulated by Spain & Portugal; if they should be suddenly deprived, as such, of the slave trade they would again become wildernesses at least in such parts as produce many of the articles in rivalship with those of the british islands — for in that state neither Spain nor Portugal would admit foreign settlers, nor will Spaniards or Portuguese emigrate to them, to work themselves – I have been astonished to find what repugnance the lower orders of people in those countries have to settling in their colonies – It is only from the Western Islands & the Canaries that they can be induced to move to America, and that only when famine and their governments drive them to it.”

Before the boat carrying the above left, Sumter added this.

Autograph letter signed, 3 pages, March 13, 1815, to Crawford. He discusses the possible shifting of the balance of power in Europe going forward and how this may affect the United States. He talks of Spain, Portugal and their South American colonies, as well as France, England and the possibility of a new continental system. “It would be a singular event if all these five countries should be allowed, by those nations who have no colonies, to fall back into that state, after they had been pronounced by the Spanish and Portuguese governments freed from it.”

Sumter’s original communications with the leaders of the Argentine revolutionaries is present, as well as their introductory letter to Crawford.

Autograph letter signed, 4 pages, January 17-18, 1815, being a copy of correspondence all in Sumter’s hand from Manuel Belgrano and Bernardino Rivadavia of the United Provinces to Sumter (in Spanish), requesting his assistance, and Sumter’s response (in French). Sumter’s letter, in part: “The search for peace that you are undertaking in Europe is of great interest not only to the people of this Continent but also to many of the great sovereigns of the other Continent…What is further worthy of their wisdom is that it is in their interests [to make this peace] because although Europe may again control the balance of the world, this balance can last no longer than the former, as was the case before, if one neglects the general prosperity of commerce…” After a brief note on Latin America, he continues, “The government of the United States is addressing the ministers in Europe, who are searching for the re-establishment of maritime rights guaranteed by the former international system…. Those in Northern Europe who are without colonies are naturally in favor of liberty of commerce in all America, the good benefit of their navigation, their revenue, and their marines.”

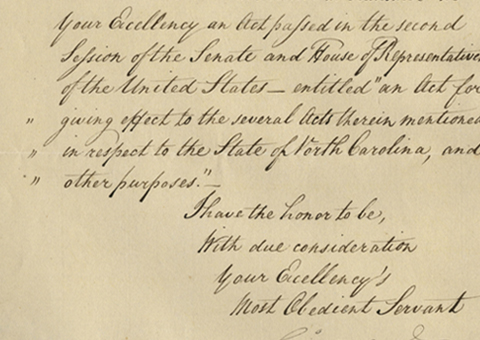

Letter signed, 2 pages, March 7, 1815, to Crawford in Paris, introducing General Belgrano & Don Bernadino de Rivadavia of Buenos Aires to Crawford in order to facilitate Argentine peace negotiations with Spain. “One of the objects of their pursuit is understood to be a pacificatory arrangement with Spain, which country they have no means of approaching.”

Sumter also included evidence of the break in neutrality on the part of the Portuguese, showing the violation of American neutral rights and demonstrating the close relations between Portugal and the English. He adds in his communications to show the Americans in Europe that he has done his part to show American goodwill.

Letter signed, 9 pages, March 1, 1815, to the Marquis de Aguilar, foreign minister of Portugal for Brazil, informing the Portuguese of his intelligence on the nature of the peace treaty and its implications for US-Portuguese relations in South America. The U.S. Minister is officially informing him that "a Treaty of Peace between Great Britain & the U.S." has been reached at Ghent and that "hostilities" will cease upon its signing by the leaders of both nations. This should end blockades and "prove beneficial to the commerce of his dominions". Sumter points out that false conditions of the treaty are being circulated by speculators and perhaps even the British, in an attempt to make themselves look better and gain favor. He assures the government of Portugal that "no principles of the U.S., nor any public rights" have been "sacrificed or compromised". An “approximation” of the Treaty is laid out and thoroughly explained, from Indian rights, to territorial disputes, to property captured, to boundaries, to fishing rights, etc. He also mentions numerous prior treaties signed by both the U.S. & Great Britain that take precedence and are still in effect.

Letter signed, 7 pages, February 25, 1815, to the Marquis de Aguiar. Sumter talks at length about the War of 1812 and the efforts of America's "gallant Seamen & Militia" to once again secure the rights of all neutral nations from the “naval tyranny" of England and restore "maritime peace”. He addresses an incident where two British Frigates, the Niger & the Laurel, using a false American flag proceeded to attack and rob a vessel between Africa and America. A second similar act took place on "the coast of China". The American Consul for Canton was in Macao at the time and is sending proof of the latter to his Excellency. Sumter uses very strong language in accusing the British and also complains of "misconduct" on the part of the Portuguese Governors of Macao and the Azores in both these episodes. He outlines charges, requests damages be paid and that the responsible officials be punished, and cites a number of previous cases involving England, Spain & Portugal.

Copy of letters from the American Consul at Canton, China and the U.S. Minister at Rio de Janeiro, February 25, 1815. Detailing an account of the seizure of the American ship Arabella in Macao harbor by the British frigate HBM Doris, with the aid of Portuguese soldiers and the Governor of Macao. A complaint is being made by the United States. This relates to the above letter from Sumter.

Copy of a letter from Aguiar, April 27, 1815, in Portuguese, relating to a diplomatic maritime dispute between the US and Britain and involving Portugal. Relating to the above incidents.

"Copy of Mr. Canning's address to the Regency of Portugal in December 1814." This includes extensive observations by Sumter, as well as a copy of another address by Lord Strangford. These appear to bolster his feeling about the developing post-war balance between the European Continent and its colonies and former colonies.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services