Trial Attorney Clarence Darrow, Famous For Debunking Supernatural Religion in the Scopes Monkey Trial, Ridicules the Idea of Life After Death

In the face of death, people “have always clung to the hopeless myth that their friends are alive after they are dead. I am thoroughly convinced that there is nothing in it.”.

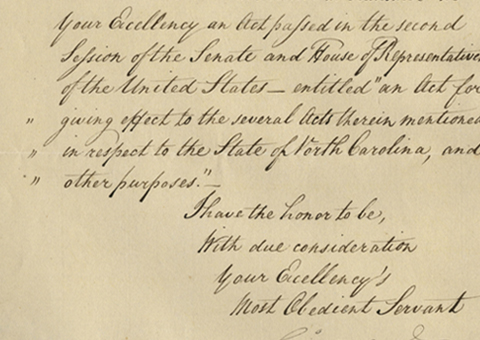

A newly discovered, unpublished letter

Clarence Darrow was, and remains, the most famous American to earn his reputation as a trial lawyer. For decades he was the defender of the underdog and fighter for civil rights, and he is remembered for his defense of John Scopes’ right to teach evolution in what...

A newly discovered, unpublished letter

Clarence Darrow was, and remains, the most famous American to earn his reputation as a trial lawyer. For decades he was the defender of the underdog and fighter for civil rights, and he is remembered for his defense of John Scopes’ right to teach evolution in what is known to history as the Monkey Trial. When he volunteered to defend Scopes, Darrow had already reached the top of his profession. His notable career started when the workers of the Pullman Railway Company went on strike in 1894, and Darrow resigned his job working for railroad interests to defend the workers against the railroad. Over the next years he defended strikers, labor leaders, and anarchists. By the turn of the century he was a noted voice for the rights of the radical left. In 1912 he defended two union officials accused of murder in the dynamiting of the Los Angeles Times building.

In 1925, Tennessee and some other southern states passed laws making the teaching of evolution illegal. The American Civil Liberties Union led the charge of evolution's supporters. It offered to fund the legal defense of any Tennessee teacher willing to fight the law in court. Scopes accepted the challenge, and in the spring of 1925 walked into his classroom and read from a Tennessee-approved textbook part of a chapter on the evolution of humankind and Darwin's theory of natural selection. His arrest soon followed. The elder statesman William Jennings Bryan was a very outspoken Christian who lobbied for a constitutional amendment banning the teaching of evolution throughout the nation, and he was selected to prosecute Scopes.

It was never the law that excited Darrow – it was the great contest over ideas. He had supported Bryan in his first presidential campaign, but Darrow was now the most prominent avowed agnostic in the nation, and openly opposed Bryan's religious beliefs. For years Darrow had been trying to engage Bryan in a public debate over science and religion, and when Bryan was named to prosecute the state’s case against Scopes, Darrow believed the trial would be the perfect platform for that debate. He agreed to defend Scopes. The trial turned into a media circus. When the case was opened on July 14, journalists from across the land descended upon the site of the trial – the mountain hamlet of Dayton, TN. Preachers and fortune seekers filled the streets. Entrepreneurs sold everything from food to Bibles to stuffed monkeys. But most importantly, the trial became the first ever to be broadcast on the brand new medium of radio, and thus became the first great philosophical debate between famous advocates argued live to a national audience.

In the courtroom, Darrow faced an uphill battle. Judge John T. Raulston carried a Bible and began each day with a prayer. He refused to overturn the anti-evolution law and would not allow scientists to testify in favor of evolution. Frustrated, Darrow came up with an unorthodox plan. On the seventh day of the trial, on a platform outside the courthouse, he called Bryan himself to the stand as an expert on the Bible. Before a crowd of two thousand people, Darrow tried to corner Bryan into admitting the unreasonableness of his belief in Genesis, hammering Bryan with tough questions on his strict acceptance of several Bible's stories, from the creation of Eve from Adam's rib to the swallowing of Jonah by a whale. On the subject of miracles. Darrow rejected the idea of them, while Bryan believed that miracles happen, though he could not explain how. The debate had escalated into a furious argument over the meaning of religion, with the entire nation listening in. In the end Scopes lost and was given a small fine, but the battle proved a victory for supporters of evolutionary theory. The trial, and Bryan and Darrow, were the subject of the film classic Inherit the Wind.

Darrow was a champion of freethought and humanism, and a foe of supernaturalism. He once wrote, “I am an Agnostic because I am not afraid to think. I am not afraid of any god in the universe who would send me or any other man or woman to hell. If there were such a being, he would not be a god; he would be a devil.” He envisaged the eventual passing of Christianity and "all the mythology that has gripped the world so strangely through ignorance and yearning.”

Autograph letter signed, on his personal letterhead, Chicago, December 26 (no year but circa 1930), to a man who had written him on the subject of life after death. “When one is in trouble, they are always seeking consolation and aid. This is one of the reasons why men have always clung to the hopeless myth that their friends are alive after they are dead. I am thoroughly convinced that there is nothing in it, forgetfulness is the only boon."

This letter is unpublished, and its discovery adds to our knowledge of Darrow’s views and methods of expressing them. A search of public sale records going back four decades reveals just one other letter articulating Darrow’s views on religion having reached that market during all that time.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services