After His 1844 Presidential Election Loss, Business Leaders Aid an Insolvent Henry Clay With a Large Cash Payment For His Services to the Whig Party

The archive of Abbott Lawrence, at the center of the confidential effort, consisting of 7 letters, including Clay’s unpublished letter of gratitude

Henry Clay: “I request, my dear sir, that you will on this, as you have been on previous similar occasions, [be] my friendly organ in communicating my sentiments of profound gratitude for this signal act of generosity. The delicate and unostentatious manner in which it has been performed greatly diminishes the repugnance...

Henry Clay: “I request, my dear sir, that you will on this, as you have been on previous similar occasions, [be] my friendly organ in communicating my sentiments of profound gratitude for this signal act of generosity. The delicate and unostentatious manner in which it has been performed greatly diminishes the repugnance which I feel in consenting to it. Be pleased to assure those to whom I am so greatly indebted, that in a reverse of our fortunes, nothing would afford me so much pleasure as to be able promptly to contribute to their relief.”

The 1844 presidential election was a close contest that turned on the controversial issues of slavery expansion and the annexation of Texas. James K. Polk beat Henry Clay by a whisker – one percent of the popular vote – in what was Clay’s last hurrah as a presidential nominee.

This loss left Clay in a financially precarious situation, in part because of the expenses of the election. His personal property was worth almost $140,000 in 1839, but by 1844 it was valued at only $51,000, and little of that was liquid. Like other men of his class, Clay carried debt. Also, he had cosigned a note for his son Thomas, but when Thomas’ business collapsed Clay found himself on the verge of bankruptcy. He was now responsible for his son’s debt, and struggled to pay his own property taxes. In response, Clay determined to liquidate his land holdings in neighboring states, took a mortgage on his home and estate, and searched for ways to economize. But by March 1845, Clay owed some $40,000 and was on the verge of losing his beloved estate Ashland.

Only the generosity of his friends saved Clay from destitution. Prominent merchants and businessmen took up a collection upon hearing about Clay’s financial distress, and paid off part of his debt. The president of the Northern Bank of Kentucky, John Tilford, wrote Clay with the good news, assuring the statesman that his benefactors considered their generosity “only a part of a debt they owe you for your long and valued services in the cause of our country and institutions.”

The men who aided Clay in his time of need were staunch Whigs, and Clay had been their foremost advocate and spokesman for a generation. They felt the need to express their gratitude, and had the wisdom to do so with subtlety. The men who initiated the project were Kentuckians who were not merely Whigs, but friends and neighbors of Clay. They included: John Tilford; General Leslie Combs, member of the Kentucky legislature, railroad pioneer, state auditor, and a noted speaker; R. P. Letcher, member of the Kentucky House of Representatives; and Kentucky physician Dr. B.W. Dudley. They determined to reach out to the great Whig money moguls in the East for funding, and to do so through the auspices of Abbott Lawrence.

Abbott Lawrence and his brother Amos were among the most important merchants, industrialists, and philanthropists of their day, and are credited as the founders of New England’s influential textile industry. They were also prime movers in favor of railroads, and in time became one of the wealthiest families in the United States. Abbott represented Massachusetts in Congress several times, and was an active advocate of Henry Clay’s “American system”, which consisted of three mutually reenforcing parts: a tariff to protect and promote American industry; a national bank to foster commerce; and federal subsidies for roads, canals, and other “internal improvements” to develop profitable markets. In September 1842, he was president of the Whig Convention in Massachusetts that advocated Clay for President, and in 1844 he was a delegate to the Whig National Convention that nominated Clay. In the 1844 campaign, Lawrence was one of Clay’s most ardent supporters.

The effort to aid Clay was kicked off by this Autograph letter signed, 4 pages, Lexington, KY, November 25, 1844, to Abbott Lawrence, signed by Dudley, Letcher and Combs, and marked “Confidential”, laying out the need and their proposition. “We desire to address you upon a subject which, although of much delicacy, we are sure will greatly interest your feelings… we desire you will consider it is strictly confidential. We will not dwell upon the grief which we know you equally share with us, as to the disastrous result of the presidential election. The great Leader of the Whig Party, and their unsuccessful candidate, now in the eve of life, is laboring under the embarrassment of considerable debt. Had his life been dedicated to the pursuit of his profession and his private affairs instead of to the public service, he would now doubtless be an opulent man. As it is, if he could dispose of his out lands, he would be able to extinguish his debts, which, with his economical habits would always afford him an ample support. But this operation, always difficult and dilatory, is under the present aspect of affairs almost impossible to ordinary purchasers. And without some assistance he may be reduced to the necessity of disposing of his long favorite residence of Ashland…

“A principal part of the debt which now embarrasses him, was contracted under circumstances characteristic of his well-known generosity and magnanimity. One of his sons who had been engaged in the manufacture of hemp, in consequence of the sudden great depression in that business… was unfortunate and made a conveyance of all of his property for the benefit of all his creditors pro rata and without any preference… Mr. Clay voluntarily relinquished his interest in the conveyance, and the consequence was that they [the creditors] were paid everything and he [Clay] nothing. The sum thus lost ($25,000) would relieve Mr. Clay from his embarrassments and render him perfectly easy. We know how agreeable it would be to him to obtain that sum by a sale of his out property and with that view we have obtained and transmit here with a memorandum descriptive of it, and assigning what is supposed to be its intrinsic value.

“Our object in addressing you as a prominent friend of Mr. Clay is to request your friendly consideration of the matter, and that you will consult confidentially with other friends, and ascertain and inform us if the very desirable purpose in view, can be accomplished. If purchasers for the whole could not be found, one or more of the tracts of land designated in the memo might be disposed to such friends as might be inclined to aid him. It is proper that we should inform you that we are the personal and political friends of Mr. Clay, as well as his neighbors, but have not means ourselves, nor do we know where they could be had in this vicinity, to afford the desired assistance and relief…”

The Kentuckians also sent Lawrence the memo mentioned above, which was a list and description of the tracts in Illinois, Indiana, Missouri and Ohio that they were proposing the moguls buy from Clay (since there were no other likely buyers), and this list is part of this archive. These lands are described in some detail, with notations about the quality of the lands and their potential uses (whether they are fertile for farming, useful for timber, etc.). The total value for these tracts is given as $27,275.91. That list, in a clerical hand, ends by stating, “This is very good land and is partly occupied. Upon all the above lands the taxes have been paid regularly up to this time, and the titles are unquestionable.”

Also included is Lawrence’s retained clerical copy of the Kentuckians’ letter, at the end of which it is noted that Lawrence had reached out and sent copies of it to John Jacob Astor, businessman, merchant, fur trader, and real estate tycoon, who was the first multi-millionaire in the United States; Stephen Whitney, merchant in New York City whose fortune was considered second only Astor’s; M.H. Grinnell, merchant, shipper, Congressman, and president of the New York Chamber of Commerce; and John L. Lawrence, New York State senator and a prominent Whig. There is a P.S. stating: “Well aware of Mr. Clay’s great reluctance to incur any pecuniary obligation, we have assumed much responsibility & you will excuse us for desiring this to be known only to a few friends of that gentleman.” Below that, headed as “Memorandum” is a summary of the list and description of the tracts. Others besides these men were also notified.

Just six days after the Kentuckians’ letter to Lawrence, Henry Timberlake Duncan penned one to him as well. Duncan was a farmer, livestock breeder, and Whig, as well as a friend of Clay’s. He acknowledged the existence of the previous project, but here presents his own alternative method of helping Clay by what we now might call crowdsourcing – raising a large sum by having many contributors paying very small amounts each. Autograph letter signed, 4 pages, Lexington, KY, December 1, 1844, to Lawrence, making his case to help Clay. “I take the liberty… to address you upon a subject of touching interest to all true Whigs…. the national feeling and gratitude to our illustrious leader Henry Clay, a name dear to every patriot… Of all the projects coming under my notice, that which proposes to raise the sum of $100,000 to be suitably invested and given to Mr. Clay strikes me as decidedly the most suitable. This is to be raised in sums of not exceeding $5 to an individual. This sum I would propose to invest in the bonds of glorious old Massachusetts and Kentucky in sums of $50,000 of each… I could not address one my dear sir where I should expect more of sympathy and generous and patriotic impulses then in your own noble heart…”

Author George W. Holley of New York was the next one to write Lawrence. Autograph letter signed, 3 pages, Niagara Falls, January 11, 1845, setting out a desirable goal of relieving Clay “from his monetary difficulties and this too in a manner that shall entirely spare his feelings as a private citizen.” He went on to propose that the movement to erect an “enduring memorial” to Clay undertaken by Clay Clubs around the country be utilized as a vehicle, by raising more money than was required for a memorial, “and then presenting the balance of whatever sum may be thus raised directly to him.” He then presented a rather surprising proposition, stating that Clay “if he was able and his duty to his family would permit, would be glad to emancipate all of his slaves.” This theory may be based upon the fact that Clay had, despite his financial difficulties, just liberated one of his finest slaves.

Lawrence was sympathetic and ready to help by doing something, but he had aided Clay financially before. He was not immediately comfortable with the notion that the nation’s wealthiest men, whose interests Clay had publicly championed, and some of whom – including himself – had already come to Clay’s financial assistance previously – be seen to ratchet up this aid and essentially pay Clay a huge sum – what in today’s dollars would be well over a million dollars. On March 13, Lawrence wrote Clay directly about the matter, to inform him that he had “determined quietly to raise from your friends and mine, a few thousand dollars” to help reduce the “pecuniary obligations that might press upon you.” He went on, however, to state that there was “a general movement among our people to raise a large sum for an individual [Clay], for whom I have more than once in bygone years successfully exerted myself, to clear him of debt.” Therefore, Lawrence informed Clay, “I could not under past and present circumstances unite In this movement and maintain my own self-respect.” He then substituted his own plan, which was “raise a small sum for the relief of a friend for whom I entertain the truest friendship.” He would contribute $500 and ask others to do the same, But he was not done with the letter when he apparently had pangs of regret, telling Clay that he “could raise a larger sum of money…and much more if I were to make a general appeal to your friends.”

In the end $4750 was initially raised for Clay’s relief, of which $4,250 was sent by Lawrence to John Tilford, president of the Northern Bank of Kentucky, to be applied to Clay’s $7,000 debt with that bank. Tilford wrote to Clay on March 20, 1845, that he had received the funds forwarded by Lawrence “from friends who are desirous of contributing to free you from pecuniary cares,” to be applied to “the payment of that much of your indebtedness“ to the Northern Bank of Kentucky.

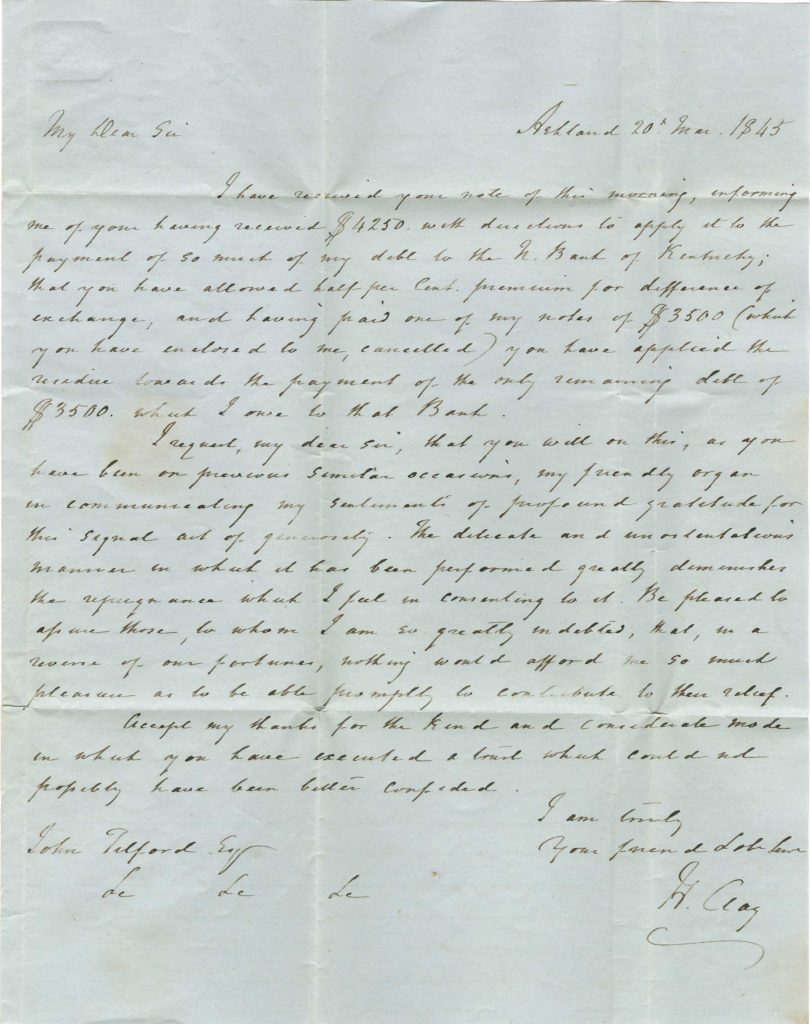

Clay responded that same day. Autograph letter signed, Ashland, Kentucky, March 20, 1845, to Tilford. “I have received your note of this morning, informing of your having received $4250 with directions to apply it to the payment of so much of my debt to the Northern Bank of Kentucky; that you have allowed half percent premium for difference of exchange, and having paid one of my notes of $3500 (which you have enclosed to me, cancelled), you have applied the residue towards the payment of the only remaining debt of $3500 which I owe to that Bank. I request, my dear sir, that you will on this, as you have been on previous similar occasions, [be] my friendly organ in communicating my sentiments of profound gratitude for this signal act of generosity. The delicate and unostentatious manner in which it has been performed greatly diminishes the repugnance which I feel in consenting to it. Be pleased to assure those to whom I am so greatly indebted, that in a reverse of our fortunes, nothing would afford me so much pleasure as to be able promptly to contribute to their relief. Accept my thanks for the kind and considerate mode in which you have executed a trust which could not possibly have been better confided.” The integral address is still present, addressed to John Tilford, Esq., Lexington. This letter may be unpublished, as it does not appear in “The Papers of Henry Clay,” nor appear when searched for by content.

The following day Tilford wrote to Lawrence. Autograph letter signed, Northern Bank of Lexington, Kentucky, March 21, 1845. “I am in receipt of your letter of the 13th in which a check for $4250, which I have applied as instructed to the discharge of that amount of Mr. Clay’s indebtedness to this bank. I enclose his letter acknowledging the receipt of it.” Thus Clay’s letter to Tilford came into Lawrence’s hands.

Lawrence did in fact do more. He went to some of his friends, and on April 2, Tilford wrote Clay that he had received an additional $5,000 from Lawrence. This paid off Clay’s debt to the bank and reduced the debt he owed to another lender.

There are 7 pieces in this, Lawrence’s own archive relating to aiding Clay, in this important but little known incident. It is particularly fascinating to note that Lawrence and the others were certainly concerned about appearances and wanted things to be confidential, But if today a public servant received funds to pay his personal expenses from persons and firms that had business before the government, and that the public servant could influence, it would be widely considered unethical , and might constitute bribery.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services