Winston Churchill Denies He Was a Warmonger Who Helped Bring on World War I

This was the precise accusation that led to his being ostracized during his Wilderness Years 1933 to 1939 - that he had pushed for World War I to break out and was now hoping to stoke another.

"My view was that if war was inevitable this was by far the most favourable opportunity and the only one that would bring France, Russia and ourselves together. But I should not like that put in a way that would suggest I wished for war and was glad when the decisive...

"My view was that if war was inevitable this was by far the most favourable opportunity and the only one that would bring France, Russia and ourselves together. But I should not like that put in a way that would suggest I wished for war and was glad when the decisive steps were taken."

In the years before World War I, Churchill was First Lord of the Admiralty, and as such a member of Prime Minister Asquith's Cabinet. In that post, he gave impetus to several reform efforts, including development of naval aviation, the construction of new and larger warships, the development of tanks, and the switch from coal to oil in the Royal Navy.

Following the assassination of Archduke Franz-Ferdinand of Austria by a Serbian nationalist on June 28, 1914, there seemed at first to be little immediate threat to European peace. Churchill continued with his plans to effect economics in the Naval budget and a test mobilization of the Third Fleet replaced the usual summer maneuvers. But on July 24 the Austrian Government issued a stringent ultimatum to Serbia, one it could not fully meet, as a result of which Russia mobilized and rushed to Serbia's aid. This set off mobilizations in France, Germany and Austria. Suddenly, Churchill wrote his wife, "Europe is trembling on the verge of a general war." On July 26, Churchill and the First Sea Lord, Prince Louis Battenberg, cancelled the Third Fleet test so as not to diminish that fleet's readiness. Churchill began preparing for war, signaling the Mediterranean Fleet: "European political situation makes war between Triple Alliance and Triple Entente Powers by no means impossible." When Germany declared war on Russia on August 1, Churchill implemented emergency measures throughout the United Kingdon, even though these actions were not approved by the Cabinet. Watchers were placed along the coastline, harbor were cleared, bridges were guarded and all boats were searched. The First Fleet was quietly moved from Portland Head and took up war stations in the North Sea. Moreover, Britain informed France and Germany that Britain would not allow German ships through the English Channel or the North Sea in order to attack France.

There was, however, considerable division among Cabinet members over how Britain should respond to the crisis. Almost all were opposed to being involved in the Balkans and 12 of 18 initially voted against providing aid to France and Russia. But Churchill did not subscribe to these reservations. He argued fervently that Britain's honor and interests required her to assist France, and Belgium if the latter's neutrality was threatened. And he had little doubt about where the fault lay, as even then he distrusted the intentions of Germany and placed sole blame on Germany and Austria. He later wrote in "The World Crisis" that "The Germans had resolved that if war came from any cause, they would take and break France forthwith as its first operation. The German military chiefs burned to give the signal."

Some of his colleagues in Whitehall, as well as citizens around the country, were thankful for his positions and his diligence, but others thought that he relished battle a little too much. Prime Minister Asquith thought that Churchill was a little too bellicose, and future Prime Minister Lloyd George recalled of the day Britain joined the war: “Winston dashed into the room, radiant, his face bright, his manner keen, one word pouring out after another. You could see he was a really happy man.” Sir Maurice Hankey later commented that "Winston Churchill is a man of a totally different type from all his colleagues. He had a real zest for war. If war there must needs be, he at least could enjoy it." Churchill's support came from rather strange quarters. Lytton Strachey, a member of the pacifist Bloomsbury group, said that "God put us on an island and Winston has given us a navy. It would be absurd to neglect these advantages." Churchill recognized his own strengths and weaknesses. He wrote to his wife days before war was declared: "Everything tends towards catastrophe and collapse. I am interested, geared up and happy. Is it not horrible to be built like that? The preparations have a hideous fascination for me…Yet I would do my best for peace, and nothing would induce me wrongfully to strike the blow."

War fever swept Britain at the end of July and during the first days of August 1914. When Germany ignored Britain's ultimatum demanding the honoring of Belgian neutrality, on August 4 the British government declared war against Germany and the Austrian-Hungarian Empire. People were jubilant about the war throughout Europe; it was indeed the last of the wars entered into with enthusiasm. Those politicians who had led their peoples into war were very popular, and young men everywhere took up arms, expecting glory and an end to the struggle before Christmas. That's how World War I started, but not the way it ended. The war stretched until November 11, 1918, resulted in 37,000,000 casualties, impoverished Europe, and was simply the most miserable, bloody, fetid, discouraging war up to that time. In the years immediately after the war, people began to question the necessity for the war altogether, with many openly considering the war a pointless waste. To be accused of warmongering for the outbreak of World War I was no small thing; in fact it could be damaging, both careerwise and personally. Nor did leaders involved in 1914 want to think that they had pushed the world into a catastrophe. Yet by the 1920s some were saying that Churchill was just such a warmonger, and had some responsibility for pushing the nation over the break.

In 1916 Lord Beaverbrook purchased a controlling interest in the newspaper "The Daily Express." Very influential, this paper helped bring down Prime Minister Herbert Asquith's government, which it considered inept, and it also pushed for Asquith's replacement by David Lloyd George, which was indeed the result. Soon his newspaper was the most widely read one in the world. Beaverbrook often disagreed with Churchill, but they developed a warm personal relationship, particularly after the outbreak of World War II. In that conflict, Churchill appointed Beaverbrook minister of aircraft production and supply. But they were already on friendly terms in the early 1920s; in November 1924, they dined together on the evening Churchill became Chancellor of the Exchequer, after the prime minister the most important position in the British government. About that time Beaverbrook began working on a book, which would be published in 1928 as "Politicians and the War: 1914-1916." He wanted to consult with Churchill to be sure some of his facts were straight, and Churchill, always alive to the power of words, for his part had a lively interest in making sure that the history reflected his perspectives. The matter that concerned him the most, he reveals in this letter, would be any claim touching on responsibility for the outbreak of World War I.

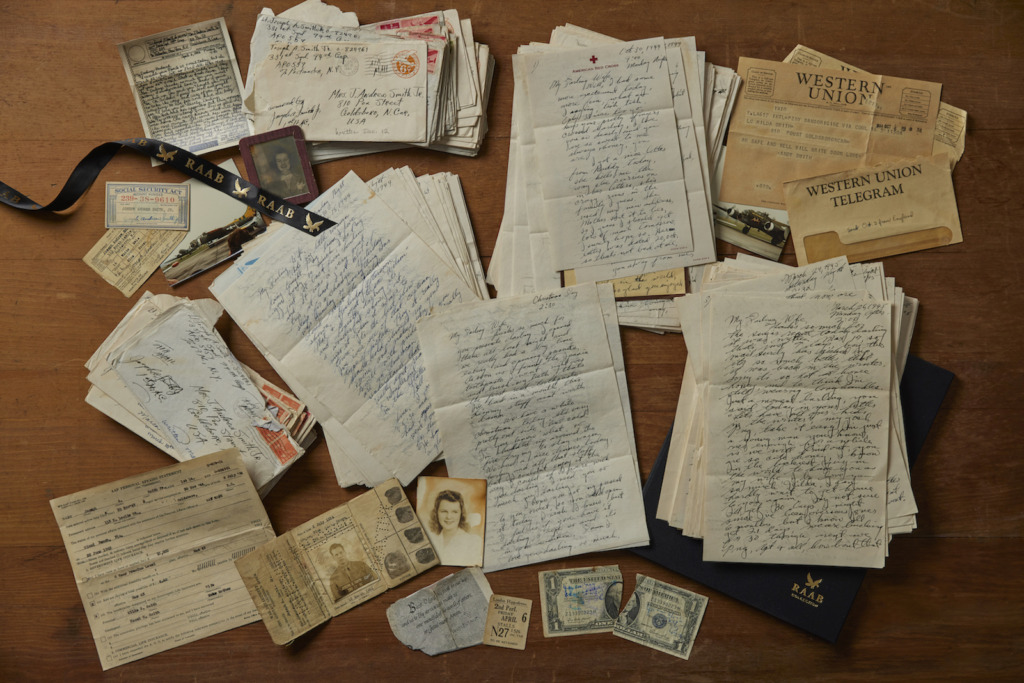

Typed letter signed, two pages, October 19, 1925, to Lord Beaverbrook, clarifying his position at the time of the war's outbreak, denying that he had actually advocated the war, and exhibiting "alarm" (to use his term) that anyone should think otherwise. "I am very much obliged to you for sending me through Freddie the passages in your Book which relate to me. You will not expect me to agree with all of them, but I have no complaint to make about any. I do not think you are accurate in saying that I proposed a consultation with you before the Budget. It was on the morrow of that event. Otherwise, I have no comments.

“You once told me that you had written some account of our talk together with F. E. at the Admiralty the night Germany declared war upon Russia, and I was a little alarmed at the description you gave of my attitude. I gather that you are not dealing with this episode in the present volume, but if you should do so perhaps you would let me see the reference. My view was that if war was inevitable this was by far the most favourable opportunity and the only one that would bring France, Russia and ourselves together. But I should not like that put in a way that would suggest I wished for war and was glad when the decisive steps were taken. I was only glad that they were taken in circumstances so favourable. A very little alteration of the emphasis would make my true position clear. I gather however you are holding the earlier and more fateful volume of your Memoirs in suspense." We don't recall another Churchill letter reaching the market on the subject of his responsibility for World War I, and position in regard to it.

Churchill was right to be concerned about such an impression and its potential impact on his career. Although he may have received a sympathetic hearing from Beaverbrook, some in positions of responsibility, and throughout the nation, were not so kind. All they recalled, or chose to recall, was not the nuance that Churchill had not advocated the war but simply stated that if it was to come, that then was the right time, but his advice and excitement entering into it. And in the end, this impression crippled, and almost destroyed, his career. The main reason that Churchill was ostracized by government leaders in the years 1933 to 1939 – his Wilderness Years – was precisely this: that while the British leadership and people were trying to avoid another war with Germany by appeasement, Churchill was again warmongering for another catastrophic war. They saw his position as dangerous and unstable, with Germany again his whipping boy. Best to keep him at arm's length. This mischaracterization of Churchill's position about Hitler, based on "old news" from 1914, almost led to a complete disaster for Britain and Europe in 1939-1940. And although most people have long since abandoned this critique of Churchill, some still hold to it. One example is the book "The Twelve Days" by G.M. Thomson, which examine's the causes and outbreak of World War I, taking the position that Churchill was "the main warmonger in 1914".

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services