President John F. Kennedy Accepts the Resignation of Llewellyn Thompson as Ambassador to the Soviet Union in Order to Bring Him Back to Washington as His Key National Security Advisor on Soviet Affairs

During the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis three months later, Thompson’s advice was largely responsible for avoiding nuclear war between the U.S. and the Soviet Union.

Lewellyn E. Thompson was one of the most important American diplomats of the 20th Century. He was the United States Ambassador to the Soviet Union at the height of the Cold War, serving two separate tours in the administrations of Presidents Dwight D. Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy, and Lyndon B. Johnson, and...

Lewellyn E. Thompson was one of the most important American diplomats of the 20th Century. He was the United States Ambassador to the Soviet Union at the height of the Cold War, serving two separate tours in the administrations of Presidents Dwight D. Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy, and Lyndon B. Johnson, and then acting as advisor to Richard M. Nixon. Few Ambassadors faced as many crises as Thompson did in Moscow – the shooting down of a U.S. U-2 reconnaissance aircraft over Russia, the great confrontation between the U.S. and Soviet Union over Berlin and the building of the Berlin Wall, very difficult summits between Soviet Premier Khruschev and Presidents Eisenhower and Kennedy, the August 1968 Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, and tensions over the Vietnam War. But there were also steps toward better relations. At Thompson's suggestion, Nikita Khrushchev became the first Soviet leader to visit the U.S. in 1959. Thompson helped arrange (and was present for) the 1967 summit in the U.S. between President Johnson and Premier Alexei Kosygin in Glassboro, New Jersey, after the Six-Day War in the Middle East exacerbated tensions. Also in 1967, the Soviet Union and U.S. agreed to begin cooperation in space, with the joint Soyuz-Apollo program. The first treaty on Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons was signed on July 1, 1968.

Thompson’s stint as Ambassador to the Soviet Union began in 1957 when President Eisenhower appointed him to the post. President Kennedy reappointed him in 1961, which was a tribute to Thompson, as new presidents usually name their people to the top diplomatic posts. Thompson’s diplomatic skills were, however, legendary, and stemmed from his philosophy, as he said, of being “a great believer in quiet diplomacy. I think that in the long run it gives a better chance for finding successful solutions to our problems.” His friendliness and willingness to talk, combined with both patience and perseverance, made him extraordinarily effective in the often difficult Cold War dealings with the Soviet Union. Thompson became well acquainted with the Soviet hierarchy, including Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, Premier Alexei Kosygin, Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko, and Anatoly Dobrynin, his counterpart as the Soviet Ambassador to the United States. He knew Khrushchev very well and had stayed at Khrushchevʼs private country dacha – which was highly unusual for a foreign diplomat – and had spent many hours with Khruschev, both alone and in meetings with other Soviet officials. Secretary of State Dean Rusk would call him “our in-house Russian during the missile crisis.”

Thompson ended his first tour in Moscow in 1962, when President Kennedy brought him home to Washington to become his Ambassador-at-Large, as a member of the Executive Committee of the National Security Council (ExComm), advising the President on Soviet affairs. President Johnson reappointed him to the ambassadorship to Moscow in 1967, and he served until 1969. He came out of retirement to advise President Nixon on the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT) negotiations with the Soviet Union and represented the United States in the SALT talks from 1969 until his death in 1972. He thus was able to provide valuable insight into Soviet thought to four American presidents. Secretary of State William P. Rogers called him “one of the outstanding diplomats of his generation.”

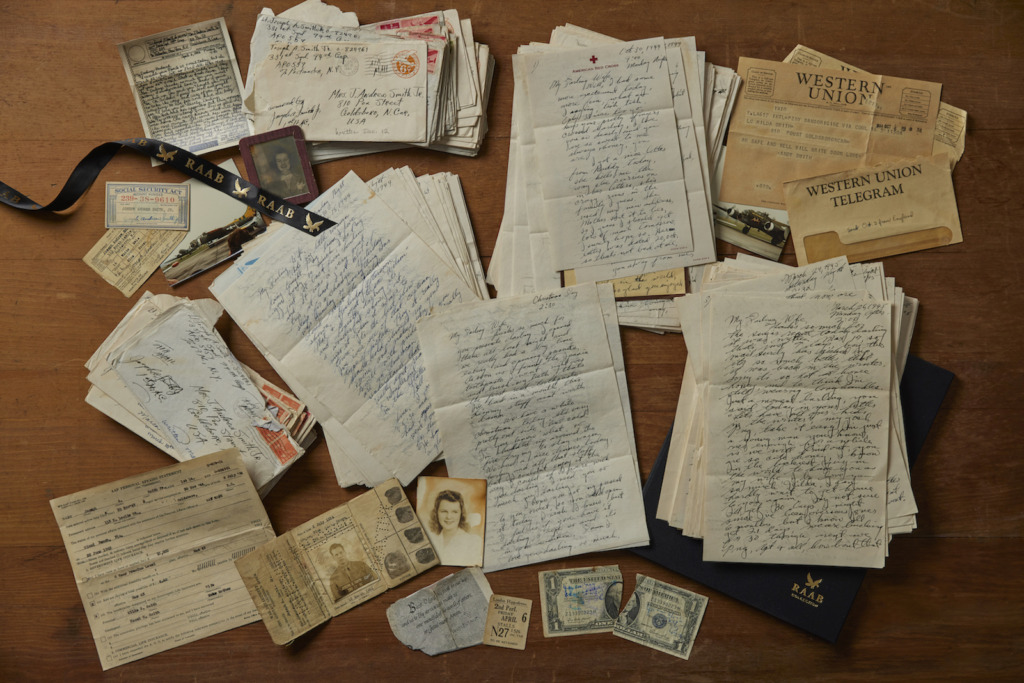

Typed Letter Signed, on White House letterhead, Washington, July 10, 1962, to Thompson, both accepting his resignation and mentioning his new position with the National Security Council. “I have your letter of resignation as Ambassador to the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, and I accept it effective on the appointment and qualification of your successor. On behalf of our Government, I wish to thank you for your devoted and dedicated service. Your career has been distinguished by continuous outstanding performance. I am deeply pleased that you will shortly undertake another important assignment.” This letter would have major implications for history.

Thompson was barely home before he had to wrestle with the Missile Crisis in October 1962. That crisis pitted the United States and the Soviet Union nose to nose, closer to nuclear war than they ever had been or ever would be. In the early evening of Friday, October 26, 1962, as war over the Missile Crisis seemed inevitable, Khrushchev sent Kennedy a conciliatory letter in which he offered to remove Soviet offensive missiles from Cuba if the United States would promise not to invade Cuba. As Kennedy was considering that letter, Khrushchev sent a much more belligerent one early the next morning, October 27. He offered to withdraw missiles form Cuba only if the United States would withdraw similar American missiles from Turkey.

Kennedy’s advisors pondered the second letter, with some arguing for military action based on it and others considering trading the missiles in Cuba for those in Turkey. Thompson argued vociferously against either course. He resisted the idea of military action, and also opposed trading away the Turkish missiles because he knew that America’s NATO allies would perceive a trade of missiles under pressure as meaning that the United States had abandoned them. Instead, he urged Kennedy not to consider the second letter as negating the first one, but to respond to Khrushchevʼs first and conciliatory letter and to ignore the subsequent belligerent one. He knew that an American promise not to invade Cuba would let Khrushchev off the hook, since Khrushchev could claim strategic success in avoiding an American invasion. Thompson correctly perceived that Khrushchev did not want war but wrote the second, bellicose letter under scrutiny from Soviet generals and hard-line members of the Politburo. “The important thing for Khrushchev, it seems to me,” Thompson said, “is to be able to say ‘I saved Cuba; I stopped an invasion.’ And he can get away with this, if he wants to, and he’s had a go at this Turkey thing, and that we’ll discuss later.”

Ultimately, Kennedy took both of Thompson’s pieces of advice: The National Security Council meeting resulted in a letter from the President accepting the terms of Khrushchev’s first (and conciliatory) letter. Then, outside of the National Security Council, the President met secretly in the Oval Office with a small group that included Thompson, Secretary of State Dean Rusk, and Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy. He instructed Bobby to have a back-channel meeting with Soviet Ambassador Dobrynin in order to convey clandestinely to Khrushchev that, although the President could not publicly agree to remove American missiles from Turkey, the United States would dismantle those missiles in time. Echoing Thompsonʼs concerns, Bobby was told to emphasize that dismantling the missiles was not a trade. The diplomacy worked, and the Missile Crisis was over.

Dean Rusk later wrote that, although Robert Kennedy presented the proposal that the National Security Council adopted, it was Thompsonʼs idea. Others in a position to know buttressed this view. According to the memoirs of Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrinyn, at a reception for the diplomatic corps at the end of 1962, Kennedy “expressed satisfaction at the way the whole crisis was being wound down. He called over Llewellyn Thompson, pointed at him, and said, ʻNow I have a very good, cautious, and experienced adviser on Soviet affairs.’ I commented that, having such able advisers, it was also a good idea to listen to them.” Robert Kennedy echoed the Presidentʼs respect for Thompson. JFK, he said, “liked Tommy Thompson. This is obviously influenced by my personal opinion, you know, and I expect it’s based on the conversations that we had. Tommy Thompson he thought was outstanding. I also thought he was outstanding. He made a major difference. The most valuable people during the Cuban crisis were Bob McNamara and Tommy Thompson, I thought.”

This letter comes from the Thompson descendants.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services