Ernest Hemingway Explains Writing “The Old Man and the Sea” and What Motivates Him to Write, in a Remarkable and Unpublished Letter

“I write stories for myself and always have...I write standing up and I have been standing up at this damn typewriter now for about two years.”.

“I wanted to get clean away from my book and come back to the final going over completely fresh and seeing it all as new.”

Ernest Hemingway believed that what mattered in life was the journey, not the end, expressing this as “It is good to have an end to journey…; but...

“I wanted to get clean away from my book and come back to the final going over completely fresh and seeing it all as new.”

Ernest Hemingway believed that what mattered in life was the journey, not the end, expressing this as “It is good to have an end to journey…; but it is the journey that matters, in the end.” He felt that this principle applied to his literary work as well, saying the secret to writing was to set very ambitious, even unattainable, goals each time, and then work towards attaining them. In that process, a great work could, and often would, result. He amplified on this in his Nobel Prize Banquet speech: “For a true writer each book should be a new beginning where he tries again for something that is beyond attainment. He should always try for something that has never been done or that others have tried and failed. Then sometimes, with great luck, he will succeed.”

In 1951 Hemingway wrote, and the next year published, “The Old Man and the Sea”, one of his most famous books. This was the last major work of fiction produced by Hemingway and published in his lifetime, and was a summation of what he loved most. The story centers on Santiago, an aging Cuban fisherman who struggles with a giant marlin far out in the Gulfstream. In the book, he discusses the struggles of catching and gaffing (using a hook to bring in the marlin once it was close to the boat), and equates the struggle to catch this marlin as a metaphor for Santiago’s struggles with life and ambition. It ends with the man dreaming of Africa, like Hemingway himself no doubt. It is an epic of American literature and the enduring legacy of Hemingway, with echoes of Hemingway’s life throughout. Hemingway was toward the end of writing this book when on June 29 his mother died.

How and why did Hemingway write? In this remarkable letter, he provides the answer to both of these questions, while referencing his style and motivation. It turns out he wrote for himself and not others, and did so standing over his typewriter. The letter also describes the process by which he wrote, edited, and re-read, “The Old Man and the Sea”.

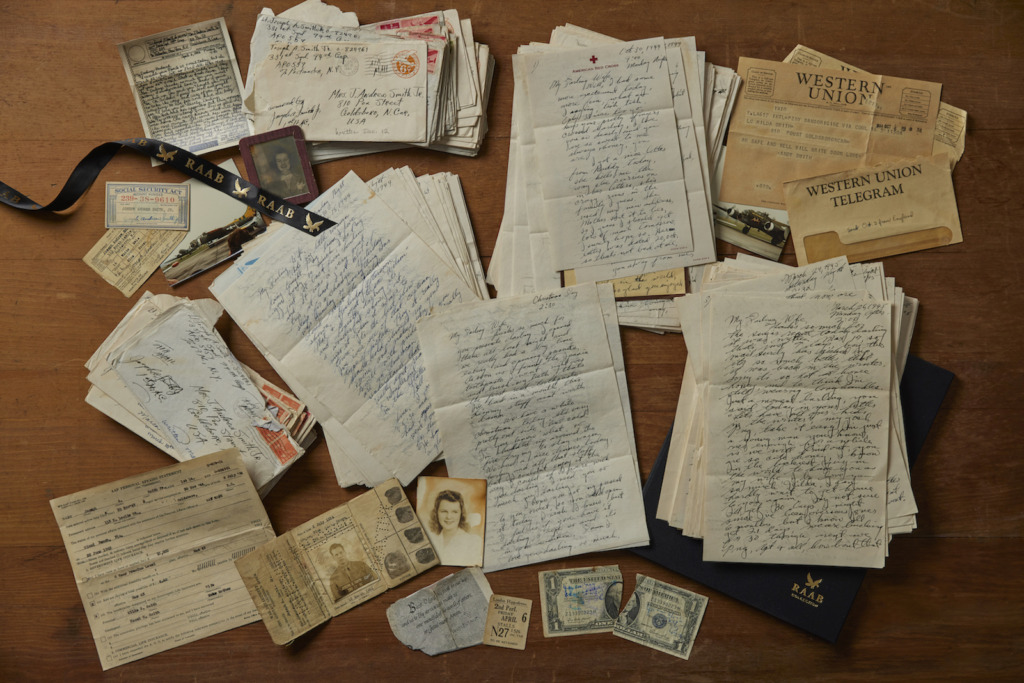

Typed letter signed, on his Cuba stationery, December 16, 1951, to Pete Barrett, Editor of Outlook Magazine, who had published an article by Hemingway in April and wanted another one. “Dear Pete: After I had your wire about not wanting anything over seven thousand words, and sent my letter to you in answer, I worked three more days on the story and then laid off. Have other things I have to do right now. It is now where I can finish it any time I am in the clear.

“When you originally wrote me about doing a piece I had just finished writing, re-writing and cutting 183, 251 words on a novel. I was all set to go on a vacation to Europe and shoot with my eldest boy Jack who has a fine shoot in Germany that he rates as a US Liaison officer to the French Army corps. I wanted to get clean away from my book and come back to the final going over completely fresh and seeing it all as new. As you know it is awfully hard to cool out and break off writing when you have been going steady at it for nearly two years. So I thought it would be a good idea to write something for you when you asked me to, as I was going very good.

“Then came the family tragedy and all the responsibilities I wrote you about. But I’d passed you the word I was going to do a piece or let you know I could not do it in time. So I was damned well going to do it whether it was the best thing for me to do or not.“With your cable, my obligation was removed and I brought the story on to where I can finish it when it is to my best interests to do so. So don’t worry about it. If I write it for myself I can put in things that happened and things that people said that I probably could not put in if I were writing it for a magazine I write articles to order. But I write stories for myself and always have. They do all right and there isn’t any hard feeling.

“I’ll write you a good piece sometime when you want one and it is convenient for both of us and we understand each other on length and terms. Right now what I want to do is get a vacation. I write standing up and I have been standing up at this damn typewriter now for about two years with something like eight days off this whole year for good behavior. Now I’m standing up to it again on a Sunday morning. Best always, Ernest.”

We can find no record of publication of this important letter.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services