As published on Nathan Raab's column on Forbes.com: http://www.forbes.com/sites/nathanraab/2014/01/27/why-thomas-jefferson-would-hate-todays-state-of-the-union-addresses.

Why Thomas Jefferson Would Hate Today's State Of The Union Address

The grand convening of Congress, the throngs of politicians marching in procession, the storied presence of the branches of government, the hushed crowd and then pronouncement of the arrival of the President, the President’s address to a nation from a raised platform, the opposition’s prompt rebuttal: we associate all these with our great democracy. Thomas Jefferson would have absolutely hated it.

The practice of giving a “Speech from the Throne” began in England and was well established by the time of our Founding Fathers. The Monarch would address Parliament when it first convened each year. His address spelled out the King’s priorities and gave a glimpse into his goals. Members of Parliament would file in regal procession to hear their bedazzling ruler. In fact, it was in a now-infamous address to Parliament in 1775 that King George III warned that the rebellion in America was a “desperate conspiracy” that would be crushed by force. These in-person addresses were a symbol of the monarchy to many of our Founders.

The framers of the Constitution did not fix an annual address by the President to Congress, instead stipulating, “He shall from time to time give to Congress information of the State of the Union and recommend to their Consideration such measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient.” This vague instruction has developed into a practice that Jefferson felt not unlike the pomp and circumstance of the “Speech from the Throne”: an annual and formal address by the President to a joint session of Congress, with the Judiciary also represented. For Jefferson, such displays belonged in the regal courts of Europe and not in the republic of the United States.

How do we know this? He told us. To the delivered State of the Union Address, or Message to Congress as it was called, Jefferson attached his antipathy toward monarchy. In 1796, before he became Vice President, he wrote a letter to a close friend in Europe, a letter whose later unauthorized publication became a source of great controversy. In it, Jefferson warned that in America, an “Anglican, monarchical, and aristocratical party has sprung up.” He meant the Federalist Party of John Adams and to which George Washington was presumably sympathetic. The goal of this party, Jefferson explained, was to “draw over us the substance as it has already done the forms of the British government.” Chief among those forms, he would clarify, were “…the pompous cavalcade to the state house on the meeting of Congress, the formal speech from the throne, the procession of Congress in a body to re-echo the speech in an answer…”

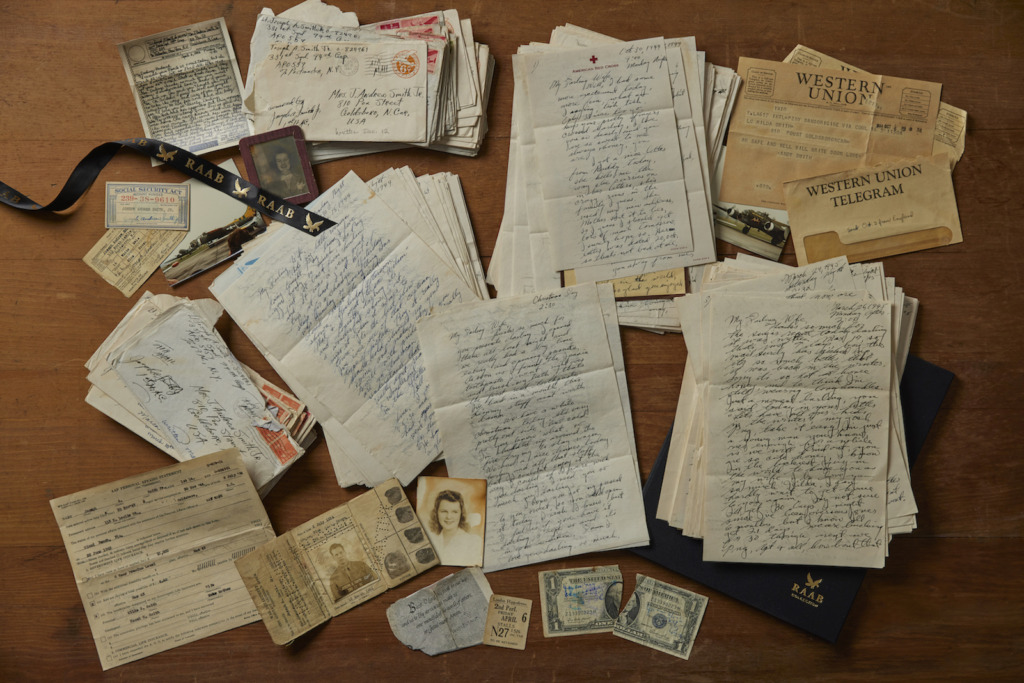

Thomas Jefferson’s 1801 Message to Congress, signed by the President and in the hand of Meriwether Lewis. The original is in the Library of Congress

In 1801, when then-President Thomas Jefferson submitted his own Message to Congress, he remedied this and in doing so set a precedent not broken until Woodrow Wilson, more than a century later. He did not physically go to Congress, nor give an actual speech. Rather, he wrote a letter and included his message. The letter, in the Library of Congress and in the hand of future explorer and assistant to the President, Meriwether Lewis, spoke of the convenience of not giving the address in person. It referenced the undesirability of forcing Congress to respond without having due time to consider the content of the address. And the message itself, which was short by today’s standards, was drafted by Jefferson, copied by Lewis and, more than likely, hand delivered by him as well.

Although it is true that Jefferson’s skills and temperament were probably better suited to the written and not spoken word, he summed up best his aversion to a practice that is now so ingrained that it is the subject of days of speculation, and is a televised, prime-time, and extravagant affair.

Two years before his death, Jefferson wrote to future President Martin van Buren about the annual addresses, referencing conversations he had with President Washington, then deceased. “I took occasion at various times of expressing to General Washington my disappointment at these symptoms of a change of principle, and that I thought them encouraged, by the forms and ceremonies which I found prevailing, not at all in character with the simplicity of republican government, and looking, as if wishfully to those of European courts…. Hamilton [Alexander, Treasury Secretary under George Washington] and myself agreed at once that there was too much ceremony for the character of our government.”