The Marquis de Lafayette Pronounces the Values That Make a Revolution Successful: “Courage in action, generosity after victory, complete selflessness”

This would be his swan song, his final major act as a revolutionary, written just days after the abdication of the King in the August 1830 Revolution.

In overthrowing a dictatorial monarch, he writes a British Parliamentarian, saying the alliance between England and France, “will bring with it the liberty, peace, and happiness of Europe.”

On December 7, 1776, Silas Deane struck an agreement with two French officers in sympathy with the American cause, Baron Johann DeKalb and his...

In overthrowing a dictatorial monarch, he writes a British Parliamentarian, saying the alliance between England and France, “will bring with it the liberty, peace, and happiness of Europe.”

On December 7, 1776, Silas Deane struck an agreement with two French officers in sympathy with the American cause, Baron Johann DeKalb and his young protégé, the Marquis de Lafayette, to offer their military knowledge and services to help achieve American independence. King Louis XVI feared angering Britain and prohibited Lafayette’s departure, but Lafayette purchased his own ship and readied for the trip. The British ambassador to the French court demanded the seizure of Lafayette’s ship, and Lafayette was threatened with arrest. He managed to set sail nonetheless and arrived in America on June 13, 1777. Lafayette then traveled to Philadelphia and tendered his services to Congress. Although his youth (he was just 19) made Congress reluctant to promote him over more experienced officers, the young Frenchman’s willingness to volunteer his services without pay won their respect and Lafayette was commissioned as a major-general. He became Washington’s aide-de-camp, and a close personal, virtually father to son, relationship developed between the two men. Lafayette was active at the Battle of Brandywine on September 11, 1777, and was wounded; after the battle, Washington cited him for “bravery and military ardor.” He was with Washington at Valley Forge, and then participated in the Battle of Monmouth. Following the formal treaty of alliance with France, Lafayette asked to return to France to consult the King as to his future service and to act as an advocate of the American cause. In 1779, Benjamin Franklin reported from Paris that Lafayette was performing the latter function very effectively at the French court. Following a six-month respite in France, Lafayette returned American and was involved in the war effort in Virginia. He played a key role in the successful siege of Yorktown in 1781, helping contain British forces long enough for them to be trapped and have no alternative but surrender. After the war Lafayette returned to France, where he became a key figure in the early days of the French Revolution. But his influence waxed and waned, he spent seven years in an Austrian prison, and over the decades faced many trials, tribulations and failures.

In 1824 the United States was in the midst of the Era of Good Feelings, was growing and progressing, and seeing a brilliant future. At the same time the generation of the Founding Fathers and Mothers who had created the republic was passing from the scene; the memory of their deeds and their ideals was growing dim, even as their grandchildren enjoyed the benefits of their labors. So the nation was looking forward and backward at the same time. Lafayette was the last surviving general of the Revolution, and although neglected in Europe, the story of his gallantry during that war, his wounds suffered at the Battle of Brandywine, his Virginia campaign that forced Lord Cornwallis into Yorktown, his relationship with the beloved Washington, were all part of the American legend. President Monroe invited him to visit. He accepted, and his 1824-5 visit to the United States became one of the landmark events of the first half of the 19th Century in America. For those who had been involved in that fight—the Revolutionary officers and those of the Society of the Cincinnati and similar organizations—the visit of their old chief would be the occasion to again light the torch just on time to pass it to a new generation. For their progeny, it would be the chance to bid a symbolic farewell to the fading, revered generation of the Revolution.

While Lafayette was returning to France, Louis XVIII died, and Charles X took the throne. As king, Charles intended to restore the absolute rule of the monarch, and his decrees had already prompted protest by the time Lafayette arrived. Lafayette was the most prominent of those who opposed the king. In the elections of 1827, the 70-year-old Lafayette was elected to the Chamber of Deputies again. Unhappy at the outcome, Charles dissolved the Chamber, and ordered a new election: Lafayette again won his seat. He was popular enough that Charles felt he could not be safely arrested, but Charles’ spies were thorough: one government agent noted “his [Lafayette’s] seditious toasts … in honor of American liberty”.

On July 25, 1830, the King signed the Ordinances of Saint-Cloud, removing the franchise from the middle class and dissolving the Chamber of Deputies. The decrees were published the following day. On July 27, Parisians erected barricades throughout the city, and riots erupted. In defiance, the Chamber continued to meet. When Lafayette, who was at La Grange, heard what was going on, he raced into the city, and was acclaimed as a leader of the revolution. When his fellow deputies were indecisive, Lafayette went to the barricades, and soon the royalist troops were routed. Fearful that the excesses of the 1789 revolution were about to be repeated, the deputies made Lafayette head of a restored National Guard, and charged him with keeping order. The Chamber was willing to proclaim him as ruler, but he refused a grant of power he deemed unconstitutional. He also refused to deal with Charles, who abdicated on August 2. Many young revolutionaries sought a republic, but Lafayette felt this would lead to civil war, and chose to offer the throne to the duc d’Orleans, Louis-Philippe, who had lived in America and had far more of a common touch than did Charles. Lafayette secured the agreement of Louis-Philippe, who accepted the throne, to various reforms.

In parliament, Sir Francis Burdett was a reformer, who at one point so infuriated those in power that he was thrown in the Tower of London. He denounced corporal punishment in the army, and supported all attempts to check corruption, but his principal efforts were directed towards procuring a reform of Parliament, and the removal of Roman Catholic disabilities. He advocated universal male suffrage, equal electoral districts, vote by ballot, and annual parliaments; but his motions met with very little support. He succeeded, however, in carrying a resolution in 1825 that the House should reconsider the laws concerning Roman Catholics. This was followed by a bill embodying his proposals, which passed the Commons, but was rejected by the House of Lords. In 1827 and 1828 he again proposed resolutions on this subject, and saw his proposals become law in 1829.

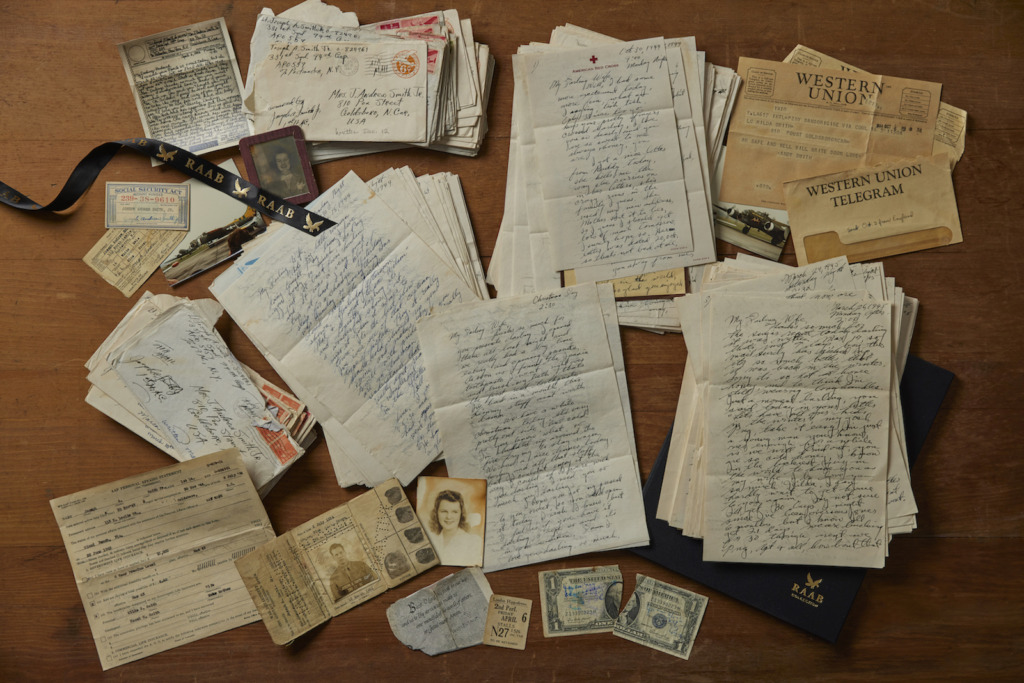

Autograph letter signed, August 12, 1830, written just days after the victory of the Revolution against Charles, to Sir Francis Burdett. “My dear Sir Francis, I received with tender recognition your friendly letter. The population of Paris deserves the praise you give her. Courage in action, generosity after victory, complete selflessness: there lies the character of this revolution. May all the movements for liberty resemble ours. For the men and women we collectively call the heads, it is not to them that glory is due. The people have done it all. My young friend Mr. Stirling, zealous lover of liberty, who leaves for London, will deliver you this letter, which I would like to have been longer. But time presses on me. I will say only that the approval and sympathy of the English people has been profoundly felt by us. This noble link of mutual friendship between the two nations will bring with it the liberty, peace, and happiness of Europe.”

With this Revolution won, Lafayette began his retirement, and passed away just four years later.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services